![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

William Critchley and John Gowing

This book marks the renaissance of interest in the potential of water harvesting for plant production in Sub-Saharan Africa. The first wave of attention was triggered by the widespread droughts of the 1970s and 1980s, and concerns about ‘desertification’. How could crop performance be ensured where rainfall was scarce, and apparently on a downward trend, and droughts increasingly common? Could the key possibly be rainfall runoff that was simultaneously being lost? Development practitioners looked with curiosity and optimism towards experience in the Negev desert in Israel (e.g. Evanari et al., 1971), and also to the USA (e.g. Dutt et al., 1981). They also began to recognize that there were traditions of water harvesting in Africa that could, perhaps, be built upon (Pacey and Cullis, 1986). Explorations through the literature even showed that there had been sporadic attempts to harness runoff waters in previous decades (e.g. in Kenya; Fallon, 1963). An array of initiatives were undertaken throughout West and East Africa in the 1980s – often driven by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and supported through drought-relief programmes. However these experiments (as many were) and experiences were occurring independently, and there was little sharing of knowledge or analysis of impact. The linguistic divide between francophone and anglophone Africa was an added barrier to exchange of understanding. For this reason, in 1987, the World Bank set out to establish the ‘Sub-Saharan Water Harvesting Study’. A further objective of the study was to uncover indigenous practices that were hitherto undocumented, or even unrecognized. A baseline literature review was first produced (Reij et al., 1988) and then, after the field study, the results were reported and analysed (Critchley et al., 1992).

The Sub-Saharan Water Harvesting Study (SSWHS) presented 13 case studies; two of them were entirely traditional, two were project-implemented designs based on traditions, and the remainder designed and implemented by projects (Critchley et al., 1992). The analysis of these cases came up with a series of recommendations, many of which will be familiar to those reading the report

20 years later. They included the need to look into reasons for adoption and nonadoption, the potential gains from sharing information between projects, the need to beware of dependence on heavy machinery, and the suggestion to coordinate incentive mechanisms within countries (Critchley et al., 1992). In many ways this current book takes that SSWHS report as its reference point, and sets out to record what we have learnt since, and where we go from here. That indeed is the basis for the ongoing project, WHaTeR that has led to the collection of much of the data analysed in the ‘country chapters’ that follow.1

It would be incorrect to say that water harvesting has been forgotten in Sub-Saharan Africa since the first phase of activities a quarter of a century ago. But it is surely true that interest has been rekindled in the last few years. That has resulted from the convergence of three current concerns: the potential impacts of climate change in dry areas, increasingly limited water for agriculture, and the imperative of feeding a growing population. Thus water harvesting is firmly back on the mainstream agenda for the drylands of Africa.

It is well to introduce a word of caution from the outset. Water harvesting is no panacea; it is not a silver-bullet solution to Sub-Saharan Africa’s problems. Too often in the last few decades, much-heralded ‘answers’ have led to disappointment at best: ‘wonder crops’ such as jojoba and tepary bean, exotic tree species such as Prosopis juliflora, the one-size-fits-all ‘training and visit’ system of extension, vetiver grass as the ubiquitous barrier to erosion, and most recently jatropha as a versatile biofuel cash-crop. But there are no such simplistic answers, and hype doesn’t help.

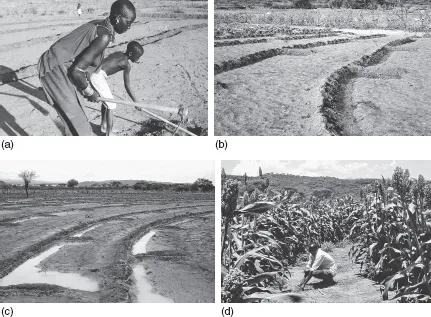

Water harvesting delivers benefits by magnifying runoff. What it does best is to increase water supplies to crops when they are at a sensitive growth stage – or to tide them over drought spells – and in these situations their performance can be dramatically improved (see Photo 1.1 for an example of a ‘contour ridge’ technology from Kenya). Borrowing economic terminology, a marginal increase in available water gives the maximum incremental yield. But it is surely self-evident that if the rains fail and drought is prolonged, then water harvesting fails with it. Equally, if rainfall is especially intense, then water harvesting will potentially increase the potency of damaging runoff. Water harvesting has a compelling role to play, but as just one part of an overall strategy of sustainable land management.

This book is not a design manual on water harvesting systems. There are plenty of these available for all different types of water harvesting – the latest is an excellent volume by Oweis and colleagues (2012) which goes into great detail regarding hydrology and engineering design for a wide range of systems. With respect to spate irrigation, Steenbergen et al. (2010) have set the standard with their FAO guidelines. The construction of sand dams is covered by a ‘practical guide’ written by the Rainwater Harvesting Implementation Network (undated; but this century). One of the current editors co-authored FAO’s early design manual for water harvesting (Critchley and Siegert, 1991). Before that, Nissen-Pieterson (1982) had written the standard design manual on rooftop harvesting for Africa. Even earlier was a handbook on design and construction of microcatchment systems (Shanan and Tadmor, 1976).

In contrast to these manuals, our book is intended to reflect on nearly 30 years of experience, and help those who are looking for pointers to the way forward for water harvesting in Sub-Saharan Africa. An earlier publication by Reij and colleagues (1996) has acted as a basic model for our approach and format. Its content, too, is closely related. But while those authors sought to establish the credibility of indigenous knowledge regarding soil and water conservation, we take that now as accepted wisdom: one of several changes that have taken place in this field over the last two or three decades. We have also made a deliberate attempt to look for ‘bright spots’, in the terminology used in Bossio and Geheb (2008), thus drawing attention to successful cases. But equally, we cite examples of less sparkling interventions: some outright failures. Our overall intention is to analyse the experiences with water harvesting and then to propose an agenda for action.

Photo 1.1a–d An example of a ‘contour ridge’ technology from Kenya: from construction to mature crop (W. Critchley).

Following two thematically cross-cutting chapters which consider water harvesting in Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, seven chapters are then dedicated to specific countries. Each of these country-based chapters looks at the history of water harvesting, its context, and its current status and prospects in that country. Figure 1.1 shows the distribution of countries discussed in the book. Then follows a chapter on policy related to water harvesting on the continent and a conclusion.

Chapter 2 sets out the context of water harvesting in the African drylands. Critchley and Scheierling look at the problems of water in agriculture, then trace the history of interventions in sustainable land management in general and water harvesting in particular. The authors move on to give an overview of key studies and assessments since the 1970s, drawing attention to the writings on water harvesting from India and West Asia/North Africa – and pointing out the common denominators as well as the differences. Principles and practices are covered, including a definition of water harvesting in the context of this book: ‘the collection and concentration of rainfall runoff, or floodwaters, for plant production’. A classification system is laid out, one that has barely changed since the writings of the 1980s and 1990s. It is stressed that water harvesting needs to be recognized as technically distinct from in situ moisture conservation, as the collection of runoff clearly requires different technologies from those that are designed to prevent runoff. Finally the chapter proposes a new concept. Water harvesting must be seen as more than just technology: thus ‘water harvesting plus’ or WH+ is proposed. This concept acknowledges aspects of agronomy, fertility management, environmental impacts, livelihoods, incentive mechanisms and enabling policy: issues that are too often overlooked yet have a crucial bearing on the success or failure of water harvesting.

Figure 1.1 The distribution of countries discussed in this book.

Chapter 3 was conceived by Bouma and colleagues as an analytical update on recent research results through a review of published articles. The focus is on production, livelihoods and uptake. While research results do not always paint the full picture – because there are many factors that determine what is researched by whom, and furthermore peer-reviewed literature often underplays the views and knowledge of practitioners – several important themes emerge. The first, simply, is that water harvesting literature is on the up: more attention is being paid to the topic. It is no coincidence that conservation agriculture, a rapidly spreading in situ conservation technology that also makes judicious use of rainfall, is another subject of increasing research. A second is the confirmation that water harvesting increases yields, and sometimes brings land back into production from a state of degradation. Dramatic improvements are found when water can be stored and used in a controlled way for cash cropping; this is referred to as the ‘business case’ for water harvesting by the authors. A third is that water harvesting can have significant environmental impacts – usually for the good – including soil conservation, improved biodiversity and increased biomass generally. However the chapter concludes that policy makers are no nearer coming to a general consensus about why there is little uptake of certain systems, though the role of subsidy dependency is clearly one main cause. Finally, and disappointingly, we haven’t yet managed to develop a consistent framework for addressing water harvesting impacts.

Chapter 4, covering Burkina Faso, is the first of seven ‘country chapters’ each of which take a single country where we have both baseline and up-to-date information. Sawadogo and colleagues explain how Burkina Faso was a ‘laboratory’ for water harvesting in the early 1980s. There were several reasons for this. The first was that the country had experienced severe drought in the 1970s and the government was leading a popular campaign against desertification. Water harvesting was perceived as having an important role to play, and fortuitously there were traditions of building stone lines to slow runoff and digging planting pits (zaï) that lent themselves to improvement. These technologies were perfectly suited to reclaiming barren, compacted land. Furthermore, the advent of ‘participatory approaches’ in the 1980s was taken up with enthusiasm by NGOs and villagers alike, leading to impressive achievements. The chapter tells us about the future evolution of these technologies – the close association with fertility management for example – but we are still unable to find accurate data on the extent of these practices or their impact on livelihoods.

Chapter 5 takes us to Ethiopia, where population pressure combined with recurrent drought and land degradation bring the issue of sustainable intensification of agriculture to the top of the development agenda. Abebe and colleagues note that this is a country where indigenous practices are acknowledged to the extent that the ‘Konso cultural landscape’ has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Efforts over the last four decades to promote water harvesting have produced some bright spots, particularly with micro-watershed interventions, which include water harvesting as part of an integrated participatory approach to sustainable land management. Other water harvesting technologies examined are floodwater harvesting (usually termed ‘spate irrigation’ in that country), household ponds and sand dams. Within the chapter there is a case study of the Abreha Watsbeha watershed in Tigray. Here, percolation ponds capturing water from a hillside have contributed to improved groundwater levels, and led to an increase in irrigation but also strikingly visible regeneration of the renowned leguminous ‘fertilizer tree’ Faidherbia albida.

Chapter 6, written by Odour and colleagues, describes interesting evolution in Kenya over the last quarter century. Kenya represented to East Africa what Burkina Faso did to West Africa during those early days of water harvesting projects and trials. Beginning with a detailed history of water harvesting in Turkana District where water harvesting formed the ‘work’ element of ‘food-for-work’ the authors show how basic mistakes were made in design and planning by one programme, while simultaneously an NGO-led project helped develop a more rational approach. They look at system development in Baringo District also; here technical success was not matched by spontaneous adoption – and furthermore the invasive exotic, Prosopis juliflora, was introduced. The chapter then moves onto a relatively new initiative, driven by farmers themselves: that of road runoff harvesting. This is located mainly in Eastern Kenya, where many farmers now tap runoff from roads and lead it into their farms. One particularly promising model combines runoff capture with ponding of the water and irrigation of vegetables in greenhouses. This is a business model with potential. The authors also show how the ‘trapezoidal bund’ – an external catchment system from the mid-1980s – has made a comeback and is being promoted once again under ‘food-for-assets’ (the more creatively named successor to ‘food-for-work’) in several districts.

Chapter 7 covers Niger. Di Prima, Hassane and Reij look at progress in this regularly drought-prone and food insecure country. Providing three case studies under the Sub-Saharan Water Harvesting Study, Niger was clearly a country of special interest at the time. While the demi-lunes microcatchment techniques of Ourihamiza were anticipated to have an uncertain future, they have, in fact, been taken up quite widely by farmers on their own; albeit with modified designs. Tassa have proved a great success, and are Niger’s equivalent of the zaï that have been so popular in Burkina Faso. Their combination with manure and fertilizer has helped many poor farmers to survive. However the SSWHS gave a less rosy prognosis for the mechanized techniques that characterized water harvesting bunds and trenches for tree planting under the Keita Valley project of the Tahou Department. Here it was predicted that these very expensive (and partially mechanized) systems would neither be maintained nor replicated without subsidies. So it has turned out. Finally there is a plea for better monitoring and scientific study, echoing the sentiments of the SSWHS.

Chapter 8 revisits Tanzania where a sustained research and communication effort during the 1990s brought about a remarkable change in perceptions and policy towards rainfall runoff. Whereas previously it had been seen as a hazard which caused erosion and flooding, the possibility of a win–win solution was recognized when it was shown that this runoff could be converted into useful soil moisture storage to improve dryland agriculture. In this chapter, Mahoo and colleagues revisit the original research site and reflect on experience after a gap of 10 years. Faltering successes with the introduction of water harvesting are contrasted with the case of the ‘majaruba’ rice production system elsewhere in Tanzania which is an undisputed water harvesting bright spot despite receiving almost no external support or promotion.

Chapter 9 highlights the special case of Sudan. Since the SSWHS, Sudan has been divided into two nations, but the study concentrated on the north of the country, which remains Sudan. Critchley, Gaiballa and colleagues point out that with probably the largest extent of water har...