![]()

PART I

The Hatching of a Genre: Origins and Influences

![]()

1

Who’s Laughing Now? A Short History of Chick Lit and the Perversion of a Genre

CRIS MAZZA

Ten years ago, in the winter of 1995, Jeffrey DeShell and I sat on the floor of his living room, brainstorming what title we would give to the anthology we had just finished. To name the book effectively, we had to boil down into a single concept what we had asserted in choosing, from more than four hundred submissions, the final twenty-two stories. Our original goal had been to determine how, in a post-Barth-and-Barthelme era, women’s experiments with form and language might be distinct from men’s. But that line of inquiry was overshadowed by the emergence of something larger, more exciting than a mere study of form. We had uncovered an atmosphere, an aura, exemplified by this example from “In the Guise of an Explanation of My Aunt’s Life” by Kat Meads:

For the sake of believability, suppose … that this family assumed all families cheated on taxes, disliked their children, killed squawking chickens bare-handed, ate calf brains with pleasure … that they accepted with humor and grace the sad but universal banality of all deviance, rendering the concept of secrecy bogus, understanding this page reveals nothing a hundred pages written by a hundred others have not already revealed, reducing the idea of family secret to the level of a bad knock-knock joke. … Sixty-two and three-quarters she was when the lid blew off, more than sixteen thousand days of cooking-cleaning-toenail clipping-monthly bleeding behind her. (53–54)

The fictions we had compiled were simultaneously courageous and playful; frank and wry; honest, intelligent, sophisticated, libidinous, unapologetic, and overwhelmingly emancipated. Liberated from what? The grim anger that feminists had told us ought to be our pragmatic stance in life. The screaming about the vestiges of the patriarchal society that oppressed us. Liberated to do what? To admit we’re part of the problem. How empowering could it be to be part of the problem instead of just a victim of it? I can’t remember the titles we rejected, but the one we ultimately chose encompassed all of the above: Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction (FC2, 1995).

Immediately we feared it would be too inflammatory, would discredit our project, would brand us literary heretics. We almost changed it. But then, how could it backfire if it was so obviously sardonic? Or, as Kelly Vie in two girls review perfectly put it in her review of Chick-Lit: “One generation of women writers wrote ‘shit happens.’ The next writes, ‘yeah, it still does, but I’ve stuck my fingers in it.’” This was the ironic intention of our title: not to embrace an old frivolous or coquettish image of women but to take responsibility for our part in the damaging, lingering stereotype.

What we couldn’t anticipate was that less than ten years later our tag would be greasing the commercial book industry machine. I’ve conducted no extensive research into culture and society to explain why chick lit was “originated” all over again, about three years after Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction was published. But a stroll through any bookstore confirms that chick lit’s second incarnation looks not at all like its first (see figure 1.1). Somehow chick lit had morphed into books flaunting pink, aqua, and lime covers featuring cartoon figures of long-legged women wearing stiletto heels. What follows is a simple synopsis from a perplexed author wondering how this all got away from us.

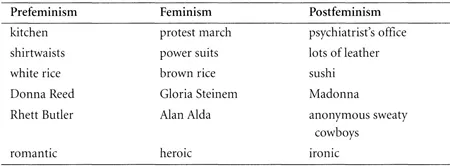

In fall of 1995, Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction was released. Reviewers would not have been interested in yet another anthology of fiction by women, but they were openly intrigued by this idea of postfeminism. “One narrator’s aunt goes berserk in her kitchen, another’s mother is transformed into a ravenous infant … and a couple decides whether to have children by playing board games,” wrote Columbus Dispatch book critic Margaret Quamme, who also made a chart to accompany her review:

In fictions that “break the boundaries of politeness,” Quamme concluded, “if feminism proposes to improve life by making social and political changes, postfeminism answers that large portions of life can’t be dealt with so rationally.”

We knew we’d found some kind of itch that had been waiting to be scratched, even if it was not always expressed the way we would have articulated it: “What does this weird title mean?” asked a reviewer in the San Francisco Bay area’s Express Books (Hagar). But despite that reviewer’s parenthetical aside, “(ooo, I just luv that word!),” a spelling I’d last seen used by cheerleaders in each other’s yearbooks, most of the first responses were not saucy or giddy but ranged from astonishment to gratitude.

“I was and remain repelled by very right-minded women who were, in the ’80s and ’90s, writing and reading like Stalinists,” says former FC2 publisher Curtis White, in describing how he hoped 1995’s Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction would affect American literature. “They had forgotten that literature is an art, that art functions through irony, and that all the sincerity in the world doesn’t make bad art good.”

Professors of literature likewise saw artistic, as well as cultural, value in Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction. Cam Tatham, associate professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, says he put Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction on his syllabus because, “I wanted to give students a sense of what had happened to conventional feminism, expressed through cutting-edge texts.” Tatham thought that chick lit helped readers “move beyond the too-familiar issues/questions of conventional feminism, deterritorializing views of victimizer/victimized.”

Pamela Caughie, professor of English and Women’s Studies at Loyola University in Chicago, also teaches postfeminist fiction. She sums up the genre that we were trying to capture in Chick Lit this way: “Postfeminist fiction does not conform to a set of beliefs about the way women are or should be. Indeed, the very writing that goes by this name resists the kind of certainty, conclusiveness and clear-cut meaning that definition demands.” Caughie further describes the genre by pointing out that the characters in postfeminist fiction might be “seen as confident, independent, even outrageous women taking responsibility for who they are, or as women who have unconsciously internalized and are acting out the encoded gender norms of our society.”

Figure 1.1 Cover of Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction, Fiction Collective 2, 1995 (artwork by Andi Olsen).

Hearing these diagnostic comments after the fact helped me fully appreciate that one doesn’t have to be a student of a movement to be a product of it. Certainly while writing my own work I did not have these theoretical summaries in my head, but one could argue that, as an editor, I should have. Simply, I was pleased to see that what I’d done on more of a gut level—shoving fiction by women into a different direction—was validated by literary and feminist scholars.

Responses such as these from critics and reviewers further elucidated our message and helped us focus the theme of the anthology’s successor, Chick-Lit 2 (No Chick Vics), published in 1996 (with a third editor, Elisabeth Sheffield).

After the release of Chick-Lit 2, something happened that could have set the course for chick lit to carry on as fiction that transgressed the mainstream or challenged the status quo, instead of becoming what it is now: career girls looking for love. When Chick-Lit 2 was reviewed in the Washington Post by Carolyn See, besides admitting that she sounded “like a grizzled old veteran down at the American Legion Hall with my medals clanking” when she demanded more plot, See observed, “You never saw so many wigs and crew cuts bleached white, or so many female genitalia. … Not many straight women here either. … The National Endowment for the Arts [NEA] funded part of this enterprise, and it is couched in words and concepts that are sure to give Jesse Helms a conniption fit.”

We believe it was Focus on the Family, a conservative watchdog organization, that spotted See’s comment and forwarded the review to Congressman Peter Hoekstra (R, MI), chair of the House Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, who pronounced the book “an offense to the senses.” An investigation ensued. Four of the books FC2 published that year were included (those supported by the NEA), and at one point Helms was seen holding one of the volumes aloft as he addressed his colleagues about the NEA.

But we weren’t Mapplethorped. Sales stayed at about what they would have been—decent to good for an independent-press book, fueled by university course adoptions. The NEA was spanked (ambiguously charged with making an effort not to fund offensive material), and despite See’s prediction, “and then the writers here can get all prissy and righteous—which isn’t as hard as it might seem, even if you’re all dolled up in minis and teddies and nose rings and black lipstick,” we didn’t meet on the Capitol steps. The little flurry failed to forever stamp the term chick lit as transgressive, visionary, or even smart.

Looking back now, I suspect if we had met on the Capitol steps in a news-conference protest (sans teddies), chick lit couldn’t, or maybe wouldn’t, have been co-opted. At least not without taking us along.

In May 1996 the New Yorker published an essay by James Wolcott titled, “Hear Me Purr: Maureen Dowd and the rise of postfeminist chick-lit.” There was our title! Although backward and not capitalized. Had Wolcott independently come up with and paired those two words? No, it could hardly be argued that he had, considering that he referenced our anthology later in the article:

One can spot this Noxzema gleam in the first-person exploits of Lynn Snowden, in the sex chat of Cynthia Heimel, Details’ Anka Radakovich, and … in pop-fiction anthologies like “Chick-Lit,” where the concerns of female characters seem fairly divided between getting laid and not getting laid.

We had to assume it was our anthology he referred to, because nothing else titled Chick-Lit was in print at the time. But Wolcott’s characterization of the anthology as “pop-fiction” would hardly apply to Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction. Neither did his summary of the stories Chick-Lit contained. Still, it’s hard to deny that Wolcott’s reference to our book was proof that he had at least seen it, if not read it. So the use of “postfeminist chick-lit” in Wolcott’s subtitle could be no accident.

And Wolcott seemed to conclude that our anthology was part of some kind of movement. Although he never directly (except in the title) called the movement “chick lit,” he did refer to the writers of whom he spoke as chicks. “Today,” he wrote, “a chick is a postfeminist in a party dress, a bachelorette too smart to be a bimbo, too refined to be a babe, too boojy to be a bohemian.” And in his summary, “The butch sensibility that imbued so much female writing in the seventies didn’t moderate or modulate into maturity. Instead, too much feminist and postfeminist writing has reverted in the nineties to a popularity-contest coquetry.”

In this last paragraph of his essay, Wolcott seemed to be describing not Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction but the chick lit yet to come.

Meanwhile, reviews of the two Chick-Lit anthologies had continued to appear, even in international publications. Nicholas Royle, novelist and book critic for Time Out: London, wrote, “The ‘postfeminist’ thing means we aren’t just getting our ears boxed by rant after rant.” After flagging several of the stories for special mention (none about dating or careers), he concluded by saying, “[This book] deserves to break out of the US and hit the UK. … In the meantime, UK publishers, isn’t it time for ‘Brit Chick-Lit’?”

At least that’s what he wrote in the version of the review he sent to me in 1996. “But for some reason,” Royle said to me recently, “(space? stupidity? bizarre prophecy?) the last line, the very last sentence, didn’t make it into the printed version.”

I choose bizarre prophecy—because it was the British book industry, two years later, that took chick lit and ran with it. Perhaps this development was aided by the rise of the Internet, homogenizer of the world. Three of our Chick-Lit authors had started a Web site called the Postfeminist Playground. “The point of liberation,” the Web site said, “is that at some point, even if you’re not totally liberated, you start trotting around flaunting your freedom.” For a while the site paid homage to its inspiration, the Chick-Lit anthologies, even quoting from the introductions. But eventually, in the bustle of their movie, book, and music reviews, some original fiction—by both men and women—and especially the advice columns, fashion critiques, and bulletin board arguments with angry feminists, the site dropped all mention of Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction and Chick-Lit 2: No Chick Vics. Whatever we’d attempted or accomplished in the anthologies was already slipping away. Or as Curtis White put it,

Chick lit has experienced that age old commodification shuffle. It was once strong and a force for something liberating. Now it’s been co-opted by people selling things. That’s okay. Let’s move on. Chick lit is dead. Long live chick lit.

The Postfeminist Playground went off the Net in late 1998. The end of the story for the Postfeminist Playground, however, is a stark allegory for the larger picture of what happened to Chick-Lit: Postfeminist Fiction. The owners neglected to retain rights to the domain name, so when their site went off the Net, a pornography site snatched the title.

As the Postfeminist Playground was shutting down, the British book industry took center stage with the publication of Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary. I didn’t take note at the time whether the chick-lit label was put to use in Diary’s initial publicity. On the current Amazon page for Fielding’s book, chick lit is not used in initial reviews for the American hardback edition from Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, New York Times Book Review, and the others.

Bridget Jones’s Diary, however, is heralded in almost every book-industry news item that discusses this new chick lit. In fact, when Anna Weinberg, writing for Book Magazine in summer 2003, was beginning what the magazine called an expose on chick lit, she said she had “just embarked on a chick lit crash course,” and then credited Bridget Jones’s Diary as “the eve of the genre.” In her crash course, she didn’t even go back as far as 1995 and never mentioned the anthology (the only book) that ever took Chick-Lit as its title.

By May 2004, Newsday.com reported, “Jump-started with Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary … bolstered by TV’s Sex and the City, [chick-lit books have] swelled to at least 240 new novels a year, according to … Publishers Weekly’...