1 Introduction

This book stems from the realisation that there remains a vital need to integrate managerial theory and practice. The search for a general theory of management has failed because the more comprehensive and inclusive any such theory becomes, the greater the barriers to its implementation. As Argyris suggests, ‘no managerial theory, no matter how comprehensive, is likely to cover the complexity of the context in which the implementation is occurring’ (Argyris, 1996: 1). Organisational learning, by emphasising change, adaptability and the utilisation of new knowledge, can offer a way of detecting and filling the gaps between theory and effective practice.

Almost all scholars would agree with the assertion that organisations must be able to learn. For example, in her wide-ranging review of the literature on organisational learning, Dixon concludes that learning is ‘the critical competency of the 1990s’ (Dixon, 1992). It is more open to question, although still widely accepted, that learning can be a source of competitive advantage. However, the actions that organisations should take to learn, and to use what they learn as a source of competitive advantage, are unclear. We are therefore in a situation where the need to learn at an organisational level is widely accepted, yet there is little or no agreement as to how organisations should achieve this. What is clear, however, is that both practitioner-oriented and academic authors have begun to acknowledge that people and knowledge are key determinants of organisational effectiveness. This realisation came to greatest prominence through the work of Peters and Waterman (1982), who championed customer service, corporate culture, vision and productivity through people as the means by which to achieve ‘excellence’. This increasing focus on behavioural issues – rather than industry analysis and structure or competitive positioning – as sources of competitive advantage has been one of the dominant themes in management thinking during the 1980s and 1990s.

The particular element of organisational behaviour under most scrutiny has changed on a number of occasions during this period – vision, customer service, decentralisation, culture, teamworking, empowerment, learning – but the legacy has been an acceptance of the need to inspire commitment and participation from all quarters of the organisation.

It is in this climate that the concept of a learning organisation has arisen to meet a clear need. In Chapter 2 the trend towards the creation of learning organisations is seen as the result of a confluence of circumstances in which a set of antecedents have come together to create the environment where becoming a learning organisation is almost an imperative. Jones and Hendry explain that ‘as an idea [the learning organisation] encapsulates a number of concerns and developments in the HRM field for bringing out the best in organizations and individuals’ (Jones and Hendry, 1994: 153). Dibella et al. believe that ‘theorists who advocate learning organisations have done a great service by envisioning the latest, if not the most critical state in an organisation’s development’ (Dibella et al., 1996: 361). Senge argues, in the introduction to his bestselling book The Fifth Discipline, that ‘the organizations that will truly excel in the future will be the organizations that discover how to tap people’s commitment and capacity to learn at all levels in an organization’ (Senge, 1990a: 4). It was Senge’s work that really brought the notion of the learning organisation to the fore, and it spawned a rash of follow-ups, including one from Senge himself (see Senge et al., 1994). However, organisational learning actually pre-dates Senge, particularly within the academic community. In Chapter 2 we will look at the work of authors such as Cyert and March (1963), Argyris and Schön (1978) and Pettigrew (1975, 1985), which laid the foundations for much of the later work on the learning organisation.

The learning organisation is an important concept in that it has attracted widespread interest from within both the academic and business communities. As we will see in Chapter 2, academics and practitioners have often taken markedly different approaches. Practitioners typically take a positive view of organisational learning, seeing it as an important route to sustainable competitive advantage. Academics, on the other hand, generally take a much more sceptical view of organisational learning, in many cases questioning whether it is anything more than a fashionable management fad with little or no real substance. One of our research goals is to assess these competing views critically and to mediate between them.

At this point it is apposite to offer a definition of a learning organisation, although we will consider this more fully in the next chapter. Returning to Senge’s work, he describes learning organisations as places where ‘people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together’ (Senge, 1990a: 3). Fiol and Lyles offer a simpler, yet more compelling, definition: ‘organisational learning means the process of improving actions through better knowledge and understanding’ (Fiol and Lyles, 1985: 803).

Organisational learning and the learning organisation

In this section we explain how the terms ‘organisational learning’ and ‘learning organisation’ are used in this book. Many previous works have used the terms organisational learning and learning organisation interchangeably. We will follow this convention here. Thus we are saying, in effect, that a learning organisation can be defined as an organisation that practices organisational learning. Conversely, organisational learning is the distinctive organisational behaviour that is practised in a learning organisation. Thus the two terms are effectively synonyms, but there are differences of nuance that should be pointed out. A learning organisation is an entity, while organisational learning is a process, a set of actions: organisational learning is something the organisation does; a learning organisation is something the organisation is.

Questions in organisational learning

The need for research into organisational learning should be evident from the above, and this view is borne out both by interest from the business community and by calls for further study from academics. Kilmann notes that ‘many academics and practitioners are currently optimistic about the prospects for organizational learning – as a theoretical concept and a social technology’ (Kilmann, 1996: 203). He goes on to point out that ‘as this timely convergence of active interest rarely happens across these two (mostly separate) communities it seems important to seize the opportunity to produce useful knowledge for organizations’ (ibid.). From a more traditionally academic standpoint, Dodgson (1993) argues that for a more complete understanding of the complexity of organisational learning a multidisciplinary approach would be required. Similarly, Miner and Mezias note that ‘the ratio of systemic, empirical learning research to learning theories is far too low’ (Miner and Mezias, 1996: 95). They go on to state: ‘we believe that the current popularity of learning as a practical vision for managers increases rather than decreases the need for rigorous systematic research’ (ibid.).

The interest of the business community in organisational learning is demonstrated by the excellent response to the questionnaire survey that forms an important part of this research and by the co-operation offered by the case-study companies. The questionnaire survey received a 40 per cent response rate, exceptionally high for a postal survey. Business interest in becoming learning organisations stems from the belief that this can be a valuable source of competitive advantage. For example, Andy McIntosh, Director of Group Personnel at Morgan Crucible, says: ‘I think the organisation that sets out to be a learning organisation is one which inevitably has a competitive advantage.’ In a similar vein, Ken Jackson, Director of Human Resources at 3M, believes that ‘a learning organisation is a successful organisation’.

On the academic side, interest in organisational learning stems from a recognition of the appeal of the concept and the academic challenge involved in testing the main propositions put forward by populist writers. As Moingeon and Edmondson note: ‘in recent popular management literature, learning is presented as a source of competitive advantage, but definitions and mechanisms involved in achieving this advantage are not specified’ (Moingeon and Edmondson, 1996: 12). They also note the lack of empirical evidence to link learning with competitive advantage, while at the same time recognising the need to ‘inspire further work in this promising new area of inquiry’ (ibid.).

Ghoshal (1987) has argued that learning as a strategic objective (and particularly as part of a global strategy) has not been given adequate attention in the literature. Similarly, Inkpen asserts that: ‘despite the logical notion that learning by organizations is essential to their success, there is a lack of synthesis and cumulative work in the area of organizational learning’ (Inkpen, 1995: 48). Jones and Hendry offer an ‘agenda for further research’, including a call for studies to determine ‘whether and how a learning organization gains a leading edge across its activities’ (Jones and Hendry, 1994: 160– 1). They also call for further research to establish whether ‘there are specific advantages for organizations if they concentrate, over time, on creating and developing attitude change linked to learning, and how this manifests itself in terms of an expanding human resource strategy’ (Jones and Hendry, 1994: 160).

A recurring theme among these calls for further research is the lack of an established link between organisational learning, on the one hand, and organisational effectiveness or competitive advantage, on the other. This is best expressed by Beer et al. (1996), who lament the lack of knowledge about the relationship between the substantive issues of business strategy and organisational learning.

It is these limitations in the current state of knowledge that are addressed in this book. The relationship between organisational learning and strategy is explicitly investigated, and the role of organisational learning as a source of competitive advantage is comprehensively examined. The main purpose of the research is to evaluate organisational learning as a means of building competitive advantage. The putative link between organisational learning and competitive advantage is a leitmotif of this book.

Major organisational learning research issues

In order to achieve the main aim noted above – the evaluation of organisational learning as a source of competitive advantage – a number of research goals were developed. The first research issues to be considered were the questions of why organisational learning is seen as important and why it has risen to prominence in recent years. In order to address this issue the following research goal was formulated: to explore the factors which have spurred the development of the learning organisation.

There was, and remains, a readily apparent need to establish exactly what a learning organisation is and how it differs from a ‘standard’ or ‘non-learning’ organisation. The best way of addressing this need is through the development of a model which enunciates the main characteristics of organisational learning. We will also consider which of these characteristics are considered most important by the case companies and why. Alternative definitions and views of the learning organisation are considered in the process.

Once we have addressed the characteristics of organisational learning, the next important issue is how these characteristics have been developed and applied in different organisational settings. A specific goal is the identification of best practice in organisational learning. Allied to this is the question of how businesses can become learning organisations. It is proposed that leadership has a vital role in creating a learning strategy, a clear vision and commitment throughout the organisation to the idea of organisational learning. An important, albeit secondary, goal is to assess the role that top management plays in creating learning organisations.

The final, and arguably most important, issues that this book addresses are the usefulness and relevance of the concept of organisational learning. These pertain directly to our main goal of evaluating organisational learning as a source of competitive advantage. There are a number of important issues. The first of these is the usefulness of organisational learning as a means of building competitive advantage. The second is the appropriateness of the learning organisation concept as a response to changes in the business environment. We will also look at the relevance of organisational learning to managers and ask whether it amounts to anything more than a disparate group of fairly standard management practices. A related issue is the relevance of organisational learning in different settings and situations. We consider the possibility that organisational learning may be exceedingly useful and highly relevant to certain groups in certain situations, but of little or no use and relevance to other groups in other situations. Overall, we shall see that the study provides interesting and original answers to a wide range of research questions. The book thus makes an original contribution to work in the field of organisational learning. It is particularly useful for its evaluation of the links between organisational learning, strategy, leadership and competitive advantage. Table 1.1 lists the research goals developed for this book and shows in which chapter or chapters they are addressed.

Research sources and methods

This section will describe the research methods chosen and the sources of data used for this book. An in-depth discussion of research methodology is beyond the scope of the book, and so we will confine ourselves to an explanation of what was done during the course of this research and why.

In the initial stage an exploratory questionnaire was sent to 400 medium-sized and large firms in the South-east of England, selected on a random basis, yielding 160 usable responses. The results confirmed that the majority of firms were familiar with the organisational learning concept and that active steps were being taken to promote the learning ideal. The companies that participated in the questionnaire are listed in Appendix 2.

The questionnaire was useful in highlighting the extent of familiarity with the organisational learning concept and the emphasis given in the literature to such things as teamworking and cross-functional working. It also served as a ‘jumping-off’ point for deeper qualitative research into the motivational and experiential aspects of organisational learning through the identification of potential research partners. Ultimately, five companies agreed to grant access to their management team, and to provide information in documentary form over and above that gathered through interviews. The five companies – 3M, Coca-Cola Schweppes Beverages (CCSB), Mayflower, Morgan Crucible and Siebe – all met the criteria for selection: they were involved in large-scale manufacturing operations; were UK-based (although not necessarily UK-owned); and were implementing, or about to implement, organisational learning initiatives across the company. Initially the organisation as a whole was considered; then we looked more closely at the use that the organisation makes of organisational learning as a source of competitive advantage.

Table 1.1 Goals of the book

The complex nature of this research made it clear that interviewing was the most suitable technique for gathering the sort of in-depth qualitative data required. The companies were comfortable with this approach and senior managers were in general happy to be interviewed. Most interviewees were open and quite willing to offer their opinions on a wide range of issues.

Appendix 1 lists the names of the interviewees at the five case companies, together with their position and the date of the interview. In total, sixty-six semi-structured interviews were carried out. Initially contact was made with a senior member of the human resource (HR) department (or equivalent department) in each company. HR directors were considered likely to be interested in the subject and also to have the necessary contacts within the organisation to facilitate the necessary interviews. For this reason, these senior managers were interviewed on more than one occasion in order to offer progress reports and maintain their support as key gatekeepers in the organisation. This also had the advantage of introducing a longitudinal element, as they could provide information on changes that had taken place since the previous interview. Interviews were requested with the chief executive or managing director of each organisation. Also high on the list of potential interviewees were people directly involved with organisational learning. In addition to this, suggestions were often made by the HR directors: ‘You should go and talk to . . . he/she has been working on a very interesting project concerning . . . .’ In this way the list of participants in the initial round of interviews was built up. Often these interviewees would suggest someone else who might be able to provide interesting information. This snowballing technique allowed interesting lines of research to be followed that might otherwise have stopped after one interview.

The approach to interviewing was semi-structured. Open-ended discursive questions and prompts were interspersed with direct questions put to all interviewees. This was considered to be the best way of encouraging individual managers to reveal how they thought and felt about organisational learning, how they had come across the idea, how they might capitalise upon it and how they assessed its potential. Instead of mirroring the official discourse, we aimed by this means to gain an understanding of the logic underlying the rise to prominence of the organisational learning concept.

The interview data were analysed using the conceptually clustered matrix technique. This involved an iterative search for recurring themes and issues in the data to codify response patterns as a prelude to the identification of similarities and differences between the five case companies. A particular strength of this technique is that it accommodates ambiguity, uncertainty and equivocation as legitimate qualifiers rather than compressing the data into predetermined categories. Meaning and generalisation are thus derived, not imposed.

In summary, the key research methods employed were to build a complex web of interviews on a strong foundation of survey research. The five case companies offered high-level access to managers who dealt regularly with organisational learning issues. The results of the fruitful interviews with these managers form the core of this book.

Outline of the book

In this section we outline the structure of the book. This may assist readers in selecting those parts of most interest. Chapter 2, ‘The antecedents of organisational learning’, focuses on those factors which have formed the driving forces behind the increased prominence and perceived significance of organisational learning. It thus addresses the first of the research goals presented in Table 1.1, the exploration of the factors which have spurred the widespread acceptance of organisational learning. The chapter begins by defining organisational learning and discussing its origins in the literature. The six antecedents of organisational learning are then discussed in detail. They are the shift in the relative importance of the factors of production away from capital towards labour, particularly intellectual labour; the increasing acceptance of knowledge as a prime source of competitive advantage; the increasingly rapid pace of change in the business environment; increasing dissatisfaction with the traditional command-and-control management paradigm; the increasingly competitive nature of global business; and the greater demands being placed on all businesses by customers. The driving forces, or antecedents, form the context in which organisational learning must be placed for it to be properly evaluated. The discussion of these antecedents is followed by an explanation of the filters through which knowledge regarding organisational learning is communicated to senior managers.

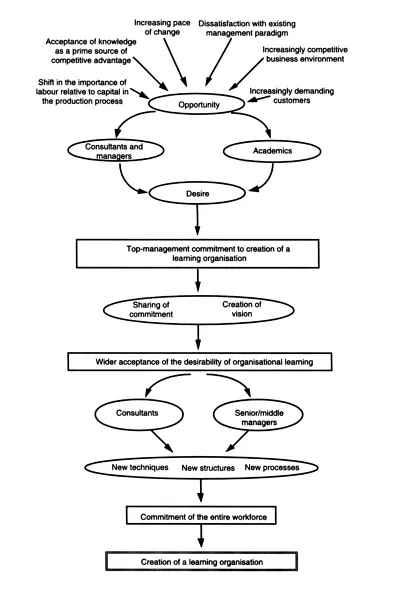

Figure 1.1 describes the author’s model of the creation of a learning organisation. It shows the role of the six antecedents in creating first the opportunity and then the desire for organisational learning. This model is used as a basis for much of the book, with sections of the model reproduced in Chapters 2 and 5. Chapter 2 discusses how top management commitment to the creation of a learning organisation develops, while Chapter 5 looks at the steps through which top management might create a learning organisation. Other chapters also consider individual aspects of the model, with sharing of commitment and creation of vision both emphasised in the case studies in Chapter 3. New techniques, structures and processes are discussed in Chapter 4.

Figure 1.1 The creation of a learning organisation

Chapter 3, ‘Organisational learning practice in the five case companies’, describes and assesses the way in which each of the five participating organisations approaches organisational learning. Each case study is considered in terms of three dimensions: strategy, structure and culture. This chapter introduces entirely new information, drawn from interviews with managers and employees in the case companies. Th...