- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Was the Industrial Revolution Necessary?

About this book

Was the Industrial Revolution Necessary? takes an innovative look at this much studied subject. The contributors ask new questions, explore new issues and use new data in order to stimulate interest and elicit new responses. By looking at it from such previously unexplored angles the book brings a new understanding to the Industrial Revolution and opens a new debate.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Was the Industrial Revolution Necessary? by Graeme Snooks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

NEW PERSPECTIVES ON THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

One of the oldest and most enduring fields of study in economic history is the Industrial Revolution. Since Arnold Toynbee first delivered his famous lectures on the subject at Oxford in the early 1880s, the Industrial Revolution has held an undiminished fascination for generations of economic historians, development economists, students, and the general public. The reason for this obsession is not hard to find—the Industrial Revolution is an event that marks the boundary between the modern period of economic growth driven by continuous technological change and earlier periods of human experience universally regarded as innocent of either rapid or sustained increases in real GDP per capita. It marked the first technological transformation—or ‘technological paradigm shift’ as I have called it elsewhere1 —since the Neolithic Revolution about 10,600 years ago. Little wonder it has attracted so much attention.

But surely after a century of detailed investigation there is little more that needs to be said about this, albeit central, issue in the modern economic history of human society. Surely now the major priority—as in the latest scholarly book on the subject2 —is to survey the vast existing literature on the Industrial Revolution so as to reach a consensus about this pivotal event. Once this has been done perhaps we should redirect our attention to economic change since the Second World War when revolutionary changes of another type—the shift of married female labour from the household to the market—occurred.3 Certainly there is a need for much more work on this later period but, as I will show in this introduction, there are many more issues to be raised concerning the Industrial Revolution.

We have only begun to scratch the surface of a field that needs to be ploughed long and deep. Even in areas which, at first sight, appear to be experiencing diminishing returns—such as the estimation of rates of growth and of changes in living standards—there is much fundamental work that remains to be done. We need to turn from reworking the estimates of others to constructing entirely new estimates based upon detailed new data sources as has been done recently with the new biological evidence. But even more importantly we need to view the Industrial Revolution from entirely different vantage points to those traditionally used. Indeed, the main objective of this book is to adopt a fresh approach to this well-worked field by asking new questions about: the wider role of the Industrial Revolution in human history; the contribution made by natural resources to this process; whether rapid and sustained growth is a modern invention; and what role the household played in the Industrial Revolution. New perspectives are required because many of the current interpretations can be traced back to the untested reasoning of the classical economists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

I ‘OLD TIMBER TO NEW FIRES’

No attempt will be made here to provide a comprehensive account of the extensive literature on the Industrial Revolution; there are excellent surveys elsewhere.4 Instead I will introduce the chapters that are to follow by indicating the extent and limitations of existing interpretations of the rate and nature of economic growth together with changes in living standards during the Industrial Revolution, and by suggesting how the new perspectives that are to follow provide helpful insights. Nor will an attempt be made in the introduction to critically evaluate the various chapters in this book, as that has been effectively done by Stan Engerman in Chapter 6.

GROWTH RATES

Early work on the Industrial Revolution by Arnold Toynbee (1884) and Paul Mantoux (1928) —and even T.S. Ashton (1948) —was more concerned with changes in economic structure and organization than with the rate of economic growth.5 This contrasts with the present state of research which places much emphasis on the rate and timing of economic growth during the Industrial Revolution. When did this ‘modern’ preoccupation emerge? It is largely a product of the post-Second World War concern of economists with Keynesian and neoclassical growth models, with the development problems of Third World countries, and with the modern growth accounting pioneered by Colin Clark, Simon Kuznets, and Richard Stone.6 The foremost exponent of this new focus upon growth rates was Phyllis Deane (1965), who in turn was influenced by Simon Kuznets.7 The slightly earlier work of W.W. Rostow on the ill-fated ‘take-off’, by contrast, was couched largely in the old-fashioned terms of structural change and was defined in terms of capital/output ratios rather than growth rates.8

In the mid-1960s, Deane made the enduring statement, which has been repeated by virtually every economic historian since then, that:

Another characteristic of a pre-industrial community which distinguishes it from an industrialized one is that its level of living and of productivity is relatively stagnant. That is not to say that there is no economic change, no economic growth even, in a pre-industrial economy, but that such growth as does occur is either painfully slow or spasmodic, or is readily reversible. It is fair to say that before the second half of the eighteenth century people had no reason to expect growth.9

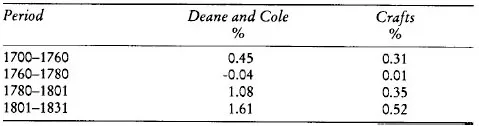

This vision of an abrupt increase in growth rates during the Industrial Revolution was interpreted by Deane as a product of structural change, largely due to the emergence of a rapidly growing industrial sector, and of technical innovation. More recently growth accountants, such as Nick Crafts and Knick Harley, have revised Deane’s growth rate estimates downwards, as shown in Table 1.1, and have placed greater emphasis upon measuring the sources of growth. Nevertheless they see the Industrial Revolution as a major discontinuity, with growth rates higher than in the pre-modern period.

Table 1.1 Old and new estimates of growth of national product per capita (compound rates)

Note: The above growth rates would be only very slightly revised in the light of the recent (1992) revisions in Crafts and Harley, ‘A restatement’ Source: Crafts, British Economic Growth, p. 45

In Chapter 4 of this book, Bob Jackson provides a skilful critique of the procedures employed both by Deane and Cole and by the revisionists Harley and Crafts. Jackson clearly shows just how indirect and precariously based these estimates really are before 1830. They are founded on just a few proxies—population, a sample of home industries, exports plus imports (or alternatively extra home industries), and net government expenditure. (This procedure makes the direct GDP estimates for 1086 presented in Chapter 3 look like the rock of Gibraltar.) Jackson argues persuasively that the differences between the initial Deane and Cole estimates and the revisions by Crafts and Harley largely ‘reflect different assumptions about the workings of the economy rather than a deeper knowledge of what was happening during the Industrial Revolution’, that ‘the rate of economic growth during the Industrial Revolution remains an open question’, and that a great deal of new detailed research is required to provide more objective estimates of growth rates.

Despite these revisions virtually all economic historians are still adamant that growth during the Industrial Revolution was much more rapid, and certainly more sustained, than whatever growth might have occurred in the pre-industrial period. They are prepared to make claims to this effect without discussing any quantitative evidence. The most recent (1993) position on this issue can be briefly summarized.10 Joel Mokyr claims: ‘The annual rate of change of practically any economic variable one chooses is far higher between 1760 and 1830, than in any period since the Black Death’. In the same volume David Landes writes: ‘The rates of change [during the Industrial Revolution] were low by twentieth century standards, and also clearly lower than these historical income accountants had expected. But were they low? They were certainly not low by comparison with what had gone before…we also know that from the 1760s growth took an upward turn and proceeded at a higher rate’; and again, ‘The Revolution was a revolution. If it was slower than some people would like, it was fast by comparison with the traditional pace of economic change.’ Like others before, Landes substitutes for historical data the argument that: if we extrapolate growth rates of about 1.0 per cent or more backwards in time we quickly reach levels of income below subsistence. As shown in Chapter 3, this assumes, unhistorically, that growth is linear and that GDP per capita and consumption per capita are the same. Finally, Knick Harley claims that real wages, the usual but invalid proxy for real GDP per capita, ‘were without secular trend’.

Why, without consulting available quantitative evidence on real GDP per capita, are modern economic historians so convinced that rapid and sustained economic growth is a modern invention? It is difficult to say, but here are a few speculations. First, these scholars appear persuaded as to the relevance of the classical growth model, if not to the period of the Industrial Revolution when it emerged, at least to the pre-modern period. The classical model, on the assumption of diminishing returns with no technological change, predicts stagnation as the natural condition of economies. Although this prediction has not been quantitatively (or even qualitatively) tested for the period before 1700, many modern economic historians accept it as a matter of faith.

Secondly, there is general and uncritical acceptance of the flawed estimates of real ‘wage’ rates for the period 1264 to 1954 published by Phelps Brown and Hopkins in 1956.11 This time series has been widely used as a proxy for real GDP per capita, despite the obvious problem (arising from a dramatically changing functional distribution of income) in doing so, and in the face of the many deficiencies of the underlying nominal ‘wage’ rate (actually piece rate) data, not least of which is its lack of representativeness (builders’ workers in a rural economy). But consider what this index purports to show: that the level of real wages in 1477 was not exceeded until 1886! So much for the increase in labour productivity that is supposed to have occurred during and after—long after—the Industrial Revolution. The Phelps Brown index of real ‘wage’ rates is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3, and the relevance of the classical growth model to pre-industrial society is dealt with by the author elsewhere.12

The final explanation as to why contemporary economic historians are willing to believe that stagnation was the lot of ‘traditional’ economies is that it is seen as an essential support for the notion of the Industrial Revolution as a revolution. But does this concept depend fundamentally upon the condition that any growth achieved during the Industrial Revolution, no matter how slow, must be more rapid and sustained than that in earlier periods? The short answer is no. The essence of the word ‘revolution’, according to the Oxford Dictionary is: ‘complete change, turning upside down, great reversal of conditions (Industrial Revolution)’. What is essential, I wish to suggest, is not that society increased the overall pace of its activities, just that the ‘complete change’ or ‘revolution’ occur within a relatively short period of time, when looking forward rather than backward. The technological change involved in the Industrial Revolution took place over a period of about 70 years or about three generations. While this may not seem rapid when looking backward from the vantage point of the present, it does appear rapid when looking forward from the vantage point of the distant past. In particular, it was very rapid in comparison with the previous technological paradigm shift—the Neolithic Revolution—which took at least a millennium to unfold. And the Neolithic Revolution occurred far more rapidly than earlier forms of technological change. In examining the emergence of human society over very long periods of time we need to look forwards rather than backwards. The Industrial Revolution was a revolution, but not on the grounds of historically high rates of growth.

In Chapter 3, the author shows that rapid and sustained economic growth has been an inherent characteristic of Western Europe during the last millennium. Evidence is also provided to support the argument that, in contrast to the claim of Deane and others, economic decision-makers before 1760 did indeed have a reason to expect growth. They expected it because they invested in it. To claim that they did not expect it not only renders irrational the increase in the longrun capital/labour ratio, but also implies that pre-modern society was the product of exogenous, rather than endogenous, processes. Human society, according to this interpretation, is merely a straw in the wind.

THE GROWTH PROCESS

According to the conventional view, there was an abrupt change in the nature of the growth process before and after the Industrial Revolution. Once again it was Phyllis Deane who introduced this idea into the modern literature. In her influential book, The First Industrial Revolution, she claims:

In effect, the levels of living in pre-industrial communities are not static in the sense of never changing, but are stagnant in the sense that the forces working for an improvement in output or productivity are no stronger over the long run than the forces working for a decline. An economy of this kind tends to be characterised by long secular swings in incomes per head, in which the significant variable is not so much the rate of growth of output as the rate of growth of population. When population rose in pre-industrial England, product per head fell: and if, for some reason (a new technique of production or the discovery of a new resource, for example, or the opening up of a new market) output rose, population was not slow in following and eventually levelling out the original gain in incomes per head. Alternatively raised by prosperity and depressed by disease, population was ultimately contained within relatively narrow limits by static or slowly growing food supplies.13

Modern economic change, according to this view, is very different to pre-modern growth, which is alleged to be dominated by population change that always increases to extinguish any one-off increase in productivity. In contrast, after the Industrial Revolution population is unable to keep up with productivity change. This radical discontinuity is not explained. Why is it that Deane’s ‘new technique of production’, which leads to an increase in productivity and output, does not give birth to further new technology? Why is it always overtaken by population? No answer is provided. And why, in the absence of annual quantitative data for real GDP per capita before 1688, was this view advanced? There appear to be two reasons. Usually there is an appeal to the work of Malthus (although there is a tendency to confuse his shortrun predictions with longrun historical outcomes) and to the real ‘wage’ rate index of Phelps B...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Preface

- 1 New Perspectives on the Industrial Revolution

- 2 The Classical Economists, the Stationary State, and the Industrial Revolution

- 3 Great Waves of Economic Change: The Industrial Revolution in Historical Perspective, 1000 to 2000

- 4 What was the Rate of Economic Growth During the Industrial Revolution?

- 5 The Industrial Revolution and the Genesis of the Male Breadwinner

- 6 The Industrial Revolution Revisited

- Notes

- Select Bibliography

- Index