![]()

Part One | Marketing Communications in Context |

Marketing communications, the most visible of marketing functions, interacts subtlety with corporate communications to form what can be a formidable force for business and other organizations, and one that impacts strongly on society generally. We are apparently exposed to thousands of stimuli each day and many of these are from the marketing and corporate communications’ arsenal belonging to myriad companies and other organizations, whether domestic, international or global. This includes the effects of branding, advertising, sales promotions, publicity and sponsorships, personal communications, packaging and so on. Marketers are faced with the challenge of integrating these activities in such a way as to maximize effective and efficient management.

This first part of the book consists of four chapters that take the reader from an introduction to the subject through to a strategic management approach to it. In Chapter 1, the integrated marketing communications mix and its environment is explored. Chapter 2 examines marketing communications theory and what it means for practice. In Chapter 3, behaviour and relationships with the other elements of the marketing effort are examined. Chapter 4 proposes a strategic framework for effective marketing and corporate communications management.

![]()

Chapter 1 | The Integrated Marketing Communications Mix and its Environment |

Chapter Overview

Introduction to this Chapter

The nature of marketing communication is explored and relationships developed with strategic marketing. Marketing communications, a mix within itself, is seen firmly as part of the marketing mix but in a strategic manner. Marketing communications as an entity is placed within an integrated marketing context surrounded by an ever-present and somewhat turbulent environment.

Aims of this Chapter

This chapter seeks to explore the nature and role of integrated marketing communications in relation to the rest of the marketing mix. More specifically it aims to:

- discuss marketing in the twenty-first century in terms of exchange and change

- situate marketing communication within strategic marketing

- explore the future of marketing and marketing communications in integrative terms

- outline the major environmental forces that impinge upon the marketing communications management function.

Marketing, Exchange and Change

Marketing is said by many to be in a state of transition. Some might say marketing is no longer strategy but a requirement, a necessity. Some of the key issues of debate today are being expressed in terms of marketing, exchange and change, and marketing has for a long time been defined in terms of both exchange and change. Marketing in this sense can be defined as ‘A social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and value with others’ (Kotler et al., 2001).1

Exchange

There are differing types of exchange. Fill (1999) lists four:

- Market – short term; self-interest driven; and independent.

- Relational – long term, supportive relationships built up between parties.

- Redistributive – where resources are shared with other parties who work as a collective unit.

- Reciprocal – that is to do with gift-giving and mutuality as opposed to self-interest of the market exchange.

This has a good deal of meaning in the context of marketing communications since the way in which marketing is seen and practised will have a large impact upon marketing communications and their management. Exchange is becoming much more of the last three, i.e. more relational, redistributive and reciprocal, as the following vignette illustrates.

Unilever, Wal-Mart and Customer Relations

In the past manufacturers have hooked into channels. In the USA for example, the likes of Procter and Gamble (P&G) have become very much associated with Wal-Mart. Procter and Gamble’s success or failure in, say, Brazil could therefore be linked to that of Wal-Mart’s there (Schultz, 1996). Thus the likes of P&G can be seen as prisoners of their own actions. One of P&G’s great rivals, Unilever, does not quite see it this way. As a manufacturer, Unilever wishes to develop closer customer relations in order to sustain growth in the long term. In order to do this it is training its managers in the business of discovering and meeting the needs of customers, but especially those of Wal-Mart, Unilever’s biggest global customer. Unilever’s ‘Wal-Mart Readiness Training Programme’ has taken on board the Wal-Mart philosophy of ‘eat what you cook’. Just as a chef would sample his or her own dishes, so Unilever’s international managers become well acquainted with the retailer by being on the superstore floor stocking shelves, answering customer queries and even helping get the goods from the stockroom to the store. This allows the manager to better meet needs by getting well acquainted with the retailer in terms of its culture, business tools and objectives. This gives Unilever competitive advantage in terms of knowing what a major customer will require in advance, such as when Wal-Mart moved into the UK by acquiring ASDA in 1999.

The training programme includes the philosophy of managers from both organizations working together on live projects, but also that of shared resources. Unilever managers can tap into Wal-Mart’s vast database ‘Retail Link’ that processes on a daily basis point of sale information from every store, thereby providing detailed sales, logistics and accounting data on every item sold – globally. However, knowledge transfer remains the key to the initiative that is seen as a ‘two-way street’ where, in particular, invaluable insights into how things are run in different countries are gained. Also, of course, managers from other countries can gain a unique insight into the situation in the USA. This includes Wal-Mart’s philosophy of low prices maintained by stripping cost out of the supply chain, a plain headquarters complete with plastic chairs and the no-gratuity policy (including paying for one’s own sandwiches during a working lunch with Unilever managers). For Unilever, it is all about making sales to the consumer via the customer, so that none of the above is alien. The fourth (of ten) of Sam Walton’s (Wal-Mart’s founder) laws reads: ‘Communicate everything you possibly can to your partners. The more they know, the more they’ll understand. The more they understand, the more they’ll care. Once they care, there’s no stopping them. Information is power and the gain you get from empowering your associates more than offsets the risk of informing your competitors.’

To sum up, two main initiatives underline this kind of partnership approach. First, the dissemination of priceless information via Retail Link; second, the appointment of individual suppliers to be ‘category captains’, where the supplier acts as an expert consultant to the category buyer and gives objective, impartial opinions and advice such as new consumer trends or a course of action against competitor activity such as the introduction of new product variants. At the end of the day it’s about fostering growth in categories. The philosophy is one of doing this in the broad category and inevitably growth will be fostered for Unilever.

Sources: Adapted from Dowman (2000) and Schultz (1996).

There appear to be two opposing viewpoints. On the one hand, there is the now traditional view of power, conflict and co-operation in channels whereby reward and punishment are the norm, i.e. there are rewards for co-operation and penalties are imposed on nonco-operation (Bradley, 1995). On the other hand lies an apparently opposing view, as described above, that is one of relationships and partnerships and mutual benefits. Are there any real differences between the two? Do they represent two different marketing paradigms or are they part of the same marketing paradigm?

Change

There are differing objectives behind certain communication. Most writers agree on at least four, i.e. inform, persuade, remind and differentiate. The predilection towards the mnemonic and/or the acronym leads writers like Fill (1995; 1999) to rearrange the words to form DRIP, i.e. differentiate, remind, inform and persuade. Change has occurred in the way in which this has evolved. Information then persuasion can be seen quite clearly in the early forms of advertising, followed by the use of reminders and the notion of differentiation of very similar products often being achieved through the communication employed. These days, however, the idea of entertainment is viewed as an essential way to explain the objectives behind certain forms of marketing communication but, in particular, television and cinema advertising. Change of all sorts is important: changing markets, for example the size of Europe as one market or the challenge from Asia. The ability/inability of multinational companies (MNCs) in the past to communicate internationally or even engage in, say, pan-European advertising has been grappled with since the 1960s2 in terms of communicating with members of the ‘global village’. In other words the adaptation/standardization debate as it applies to communication is still alive and kicking with a key question being ‘should companies think global, act local?’ We have moved into the era of the globalization of markets with very different types of companies emerging, underlining a fundamental change to the business ecosystem. Questions surrounding the new world order and the relationship between MNCs and the development of world regions impinge on many things, not least the communication process.

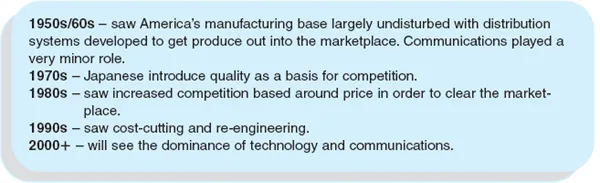

In particular, the ‘information explosion’ is upon us. The worldwide dominance of the USA is waning. We have moved chronologically from American manufacturing and distribution dominance in the 1950s and 1960s, through cost-cutting and re-engineering in the 1990s, to the dominance of the media and consumers through ownership of technology and communications in the twenty-first century (Figure 1.1).

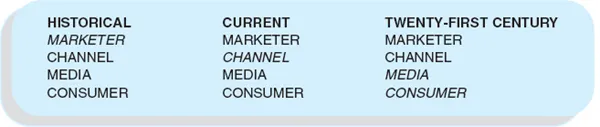

The late 1990s have seen technological influence in terms of, for example, digital technology. Corporations such as Eastman/Kodak have digital photography. If this technology were introduced too fast then this would kill off the paper and chemicals business. If too slow then they miss out to the competition. Ultimately the consumer will control this, not corporations. Levi is on the Internet. The consumer who has the technology can order direct. United Airlines offers tickets, hotel reservations and car hire – all on personal computer (PC) software. This is not good news for travel agents. As Schultz (1996) put it, the key to this transition is the transfer of information technology first into channels then to the consumer. Visually this looks something like Figure 1.2.

The future appears to be in the realms of interactivity. Fragmentation has begun and the myth of company/corporate image is dissolving before us. Coca-Cola has a thousand – maybe a billion – images worldwide. The consumer is still small but is growing fast in terms of control. The notions of change and globalization are illustrated in the vignette below.

Figure 1.1

From manufacturer to technology/communications dominance.

Source: Adapted by the author from Schultz (1996).

Figure 1.2

Source of power in the transition from marketer to media and consumer dominance.

Source: Adapted by the author from Schultz (1996).

Developments in World Regions: Taiwan, South East Asia and Global Economic Tremors

The question is, do we live in one world and if not what kind of world do we live in? On the one hand, there appears to be rapidly converging activity, interest, preference and demographic characteristics leading to readily accessible, homogeneous market groupings. On the other hand, this may very well be stereotyping across cultures that might not be possible, desirable or even necessary. The economy of Taiwan and business developments in that country, and in South East Asia generally, in the past fifty years are interesting. There was rapid growth in the 1990s until the 1997 crisis. Taiwan is part of Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation Conference (APEC), which includes the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries as well as Australia and a growing number of others. Taiwan has moved to a high-tech, high-wage economy that is more to do with niche exploitation than copycat activity and has used existing technologies in innovative ways. This strategy avoided head-to-head contests for technological supremacy. Taiwanese companies target niches with world-class products specializing in, for example, computer peripherals, microcomputers and the application of specific chips. This has not been a one-way street though. Motorola, Intel, Glaxo, Apple, Boeing, Lockheed have weighed up the ‘tigers’ and recognized their high potential, and have teamed up with local companies for manufacturing, applied research and applied design. Asia’s markets post-1997 have been rather bumpy. Towards the end of 2000, the economic prospects for the region were rather gloomy because of higher oil prices outside the region and a slowdown in US demand for electronics products. Internally concern has been expressed over corporate restructuring and financial sector reforms. However, the global outlook remained positive with projected growth of 4 pe...