![]()

Introduction

One of the dominant environmental features of the twentieth century has been the dramatic decline in forest cover. This has been going on for many years but the rate has accelerated dramatically in the last 50 years. Huge areas have been deforested in both temperate and tropical regions. Significant amounts of forests still remain but, in many places, these persist in landscape mosaics made up of residual forest patches embedded in a matrix of other land uses. Further, much of this remaining forest is regrowth rather than undisturbed old-growth forest meaning that its value for purposes such as wildlife conservation has been reduced. This deforestation process and the variety of direct and indirect causes responsible for it have been reviewed by Kaimowitz and Angelson (1998), Lambin et al. (2003) and Chomitz (2007).

Many of these former forest lands have since been used for agriculture and this has bought great wealth and food security to large numbers of people. Some of these agricultural lands have now been settled for many years and have achieved ecological stability. But not all land clearing has been successful and some cleared lands are now only marginally suitable for agriculture. Some have been largely abandoned. There are a variety of reasons for this. In certain cases it was because the soils or environmental conditions were always unsuitable for any kind of agriculture meaning that failure was inevitable. In other cases inappropriate cropping methods or over-grazing caused damage. Sometimes economic or social constraints have led to the decline of what were initially successful agricultural enterprises.

The process of deforestation and forest fragmentation has had many ecological consequences. One of these has been the loss of considerable biodiversity, especially amongst those species requiring specialised forest habitats. But other changes have arisen from efforts to maximise agricultural production. These changes have included soil losses, soil compaction, acidification and overall fertility declines. Rivers draining these lands have sometimes been affected by sedimentation, chemical pollution (from agricultural chemicals) or salinity (UNEP 2007). At the same time, many cleared lands have become dominated by exotic weed or pest species. Some of these landscapes have undoubtedly crossed an ecological threshold and moved to a new state condition from which recovery will be difficult.

These changes have also had significant socio-economic consequences. Despite the degradation, large numbers of people continue to live in these landscapes. One estimate suggests one-third of the world’s population now suffer from the effects of land degradation with many of the most affected people being found in the world’s drier regions (UNEP 2007). A large number of these people traditionally depended on the natural capital contained in forests for food, building materials, medicines and other resources. Forest loss, together with land degradation, means these people are increasingly vulnerable to natural hazards and future socio-economic changes. Often such people are caught in a ‘downward spiral’ and are forced to make increased demands on the limited resources still available as their populations grow. Further resource degradation occurs as these demands increase. Scherr (2000) argues that under such circumstances, the best strategy is to develop ways of increasing people’s access to natural resources, enhance the productivity of these resources and involve communities in resolving management dilemmas.

Many farmers have grown trees on their land but larger-scale reforestation only became more widespread in the early years of the twentieth century when some governments began creating industrial timber plantations to make up for the loss of natural forests (see Box 1.1 for a definition of forests, reforestation and restoration). Over time private growers have taken over many of these plantations and created new ones. But, in more recent years, the emphasis has begun to change as the extent of natural forest losses have increased and the adverse ecological consequences have become more obvious. There is now increasing interest in undertaking reforestation to provide ecosystem services such as watershed protection and biodiversity conservation rather than to simply produce timber; indeed the production of goods such as timber is becoming a secondary objective in many locations. Some of the reforestation schemes now being proposed by governments and the international community are very large.

This book explores how this forest restoration might be done to generate better functional outcomes as well as improve human livelihoods. In particular, it considers the ways in which various forms of large-scale reforestation of cleared land might be implemented. This first chapter begins this exploration of how large-scale forest restoration might be undertaken by initially clarifying what is meant by ‘large-scale’ and then by exploring how much degraded land there is and the extent to which it might be available for reforestation. It also describes the context in which future forest restoration will be carried out.

Box 1.1 Defining forests, reforestation and restoration

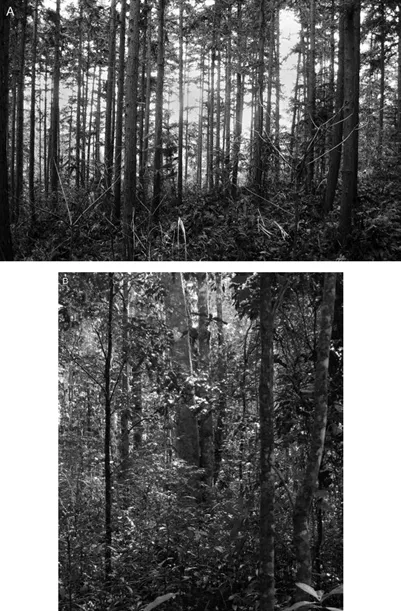

There is considerable debate over the terms used to describe various types of forest and different forms of reforestation (Carle and Holmgren 2003). Some dispute whether plantations are really forests while others point to the role of planted forests in many temperate regions contributing to conservation objectives (Meijaard and Sheil 2011). In fact there is a considerable variation in the types of planted forests and even the most simple of these can sometimes change and evolve over time to the point where they may seem like natural forests to a layman (Figure 1.1). Evans (2009) discusses some of the difficulties in defining the types of forests found along the continuum between simple, even-aged plantation forests managed on short rotations for production purposes and undisturbed natural forests. Between these extremes can be found a variety of forests differing in composition, the number or proportion of species planted, the number of age classes present (i.e. whether the forests are self-sustaining), the tree density and the spatial arrangement of the trees. The definitional difficulties include accounting for differences in the starting point, structural complexity and degree of naturalness of the forest or the purposes for which they have been established.

A particular complication involves planted forests that, over time, are colonised by additional tree species. Are these plantations or forests? Over 5 million ha of planted forests in the western USA are excluded from national statistics because of this colonisation process (Fernandez et al. 2002). And what of naturally regenerating forests that have been enriched by planting to increase the proportion of certain favoured species? Such developments have led to some referring to certain forests as being ‘semi-natural planted forests’ (Evans 2009). Unfortunately different countries use these terms in different ways. Thus Finland classifies most of its forests as semi-natural although they are planted using native species while the USA also uses mostly native species but refers to the new forests as plantations.

In the present context the following terminology shall be used (based largely on Evans 2009).

Types of forest

(i)Plantation: forest stands artificially established (by planting or direct seeding) and containing one or more species. These may be established for production or protection purposes.

(ii) Semi-natural planted forest: forests containing a mixture of planted and naturally regenerated species. Examples are: (a) even-aged plantations that, over time, have been converted to uneven-aged forests because of natural regeneration and/or external colonists reaching the site and establishing under the tree canopy; and (b) natural regeneration that has been enriched using planted seedlings.

(iii) Regrowth forests: forests that have regenerated largely through natural means following a natural or human-induced disturbance. The composition, tree density and structure depend on the time since the disturbance and may change significantly over time.

Figure 1.1 There are many kinds of planted forests: (A) a Cunninghamia lanceolata plantation in China that was established and maintained as a monoculture; (B) a 60-year-old Flindersia australis plantation in Australia planted as a monoculture but now an uneven-aged multi-species forest because of enrichment by colonists from adjoining rainforest (Photos: J. Firn).

It is difficult to prescribe a certain threshold size that must be reached before planted trees become a plantation or part of a semi-natural forest. It seems sensible to exclude single rows of trees planted along roadsides or fence lines even though these may contribute significantly to rural plantings.

Reforestation

Reforestation shall be taken to include the re-establishment of forests or woodlands at sites where woody plants were the former natural vegetative cover by deliberately planting or sowing seeds as well as by natural regeneration (excluding situations where production forests are being reforested as part of the normal silvicultural cycle). That is, it is the opposite of deforestation. Evans (2009) recognised two basic methods of re-establishing trees at cleared sites:

(i) Afforestation: the act of creating a forest at a site where trees have been absent for more than 50 years.

(ii) Reforestation: the act of re-establishing trees at sites deforested within the previous 50 years irrespective of whether or not the same species are replanted.

The problem with this distinction is that site histories are often unknown. Largely for convenience, the term reforestation shall be used here to cover both approaches.

Restoration

Reforestation can be done in a variety of ways. Restoration is sometimes used to describe forms of reforestation where the emphasis is on multi-species plantings or on some degree of ‘naturalness’ but the distinction is not always clear and two terms (reforestation and restoration) will mostly be used here interchangeably. On the other hand, the term ‘Ecological Restoration’ will be restricted to the process of attempting to restore a forest ecosystem previously present at a now degraded site. This particular type of restoration is discussed further in Chapter 4.

The meaning and significance of ‘large-scale’ forest restoration

Some explanation of the term ‘large-scale’ is needed. This is clearly a subjective term and can mean different things to different people depending on their viewpoint and circumstances. Thus, a 1,000 ha plantation area might be regarded as being relatively small-scale by some industrial growers but be seen as relatively large-scale by a community living on a 2,000 ha island. For the purposes of this book large-scale will be taken to mean:

(i)a large contiguous planted area exceeding, say, 10,000 ha;

(ii)a number of small, separate forest plantings that collectively add up to a large area even though they are scattered across a wider landscape;

(iii)a forest area large enough to sustain a breeding population of a top-order predator;

(iv)a forest area large enough to influence hydrological processes within a watershed (e.g. to lower water tables in order to reduce salinity).

Large-scale reforestation is important because this is the scale at which interventions are needed to influence and restore many of the ecological processes and functions that were changed when the original forests were removed. Small isolated patches of restored forest may be locally useful but may have little effect on restoring regional hydrological processes, combating large-scale erosion or increasing the populations of endangered species. And while a single small patch of forest might be able to supply forest products for localised use, it is unlikely to be commercially attractive unless there are other forests nearby to provide su...