- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sustainable Urban Neighbourhood

About this book

This successful title, previously known as 'Building the 21st Century Home' and now in its second edition, explores and explains the trends and issues that underlie the renaissance of UK towns and cities and describes the sustainable urban neighbourhood as a model for rebuilding urban areas.

The book reviews the way that planning policies, architectural trends and economic forces have undermined the viability of urban areas in Britain since the Industrial Revolution. Now that much post-war planning philosophy is being discredited we are left with few urban models other than garden city inspired suburbia. Are these appropriate in the 21st century given environmental concerns, demographic change, social and economic pressures? The authors suggest that these trends point to a very different urban future.

The authors argue that we must reform our towns and cities so that they become attractive, humane places where people will choose to live. The Sustainable Urban Neighbourhood is a model for such reform and the book describes what this would look like and how it might be brought about.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sustainable Urban Neighbourhood by David Rudlin,Nicholas Falk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Methods & Materials. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture Methods & MaterialsPart 1

THE ORIGINS

Any attempt to shape the future of housing must be based upon an understanding of how we have got where we are today. Our attitudes towards new development are shaped by perceptions of what has and has not worked in the past and the cultural baggage which has become associated with the home and its place in towns and cities. In the first part of this book we therefore seek to chart the way that social and economic trends along with Utopian theories and urban reformers have shaped the pattern of housing and the attitudes of developers and residents that we have today.

‘If we would lay a new foundation for urban life, we must understand the historic nature of the city’

Lewis Mumford - The City in History, Secker and Warburg 1961

Europe at night: A satellite image of Europe showing the extent of urban areas. This illustrates a sharp contrast between the land covered by Paris, Madrid and Barcelona, for example, compared to the sprawling conurbations of Britain. The reasons for this difference are explored in this chapter

Chapter 1

The flight from the city

Why is it that in Britain and America there has been such a deep enmity towards the city? Why is it that we celebrate continental cities while, for most of the 20th century, British and US cities have been reviled and even feared? If it is true that without cities we have no civilisation, what has our attitude towards cities told us about the state of our society? It is important that we reinvent the city and to do this we must understand the reasons for the Anglo-American city's fall from grace.

The golden age of cities

This was not always the case. There was a time when the builders of cities were glorified. Cities were the centre of civilisation, the places where the arts, government and commerce thrived. The design of cities was a noble pursuit attracting leading creative minds, from Vitruvius to Michelangelo, Baron Haussmann to John Nash. The building of great cities was the concern of emperors and kings, from Pope Sixtus V's remodelling of Rome as the capital of Christendom, Peter the Great's commissioning of St. Petersburg as his capital and Napoleon III's redevelopment of Paris as a city of boulevards and squares. It was in the cities of Mesopotamia and the Nile Valley that civilisation first flowered. It was in the cities of the Greek and Roman empires that European civilisation was shaped and in the cities of northern Italy where it was rediscovered through the renaissance. Cities, as centres for religion, trade and culture, lie at the foundation of modern society. Whilst academics may argue about which came first, whether cities gave birth to civilisation or whether civilisation necessitated the building of cities1, the two are inextricably linked.

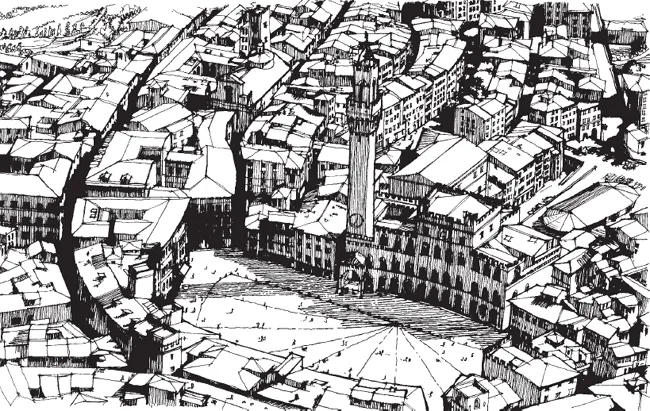

Many of the cities which predate the Industrial revolution and the motorcar, retain their appeal today. These pre-industrial cities exhibit all of the urban qualities that we prize today and on which much modern urban design thinking is founded. Perhaps the most enduring image of this pre-industrial city is the Italian hill town of Siena which has been endlessly analysed and plundered for inspiration. Indeed it is argued2 that the Commission for the European Union's ideas for the ‘compact city’3 are based more upon the unattainable ideal of the Italian hill town than the rather messier urban realities of most European cities today.

The medieval city was typically small, mixed-use, and based upon travel by foot. At the height of its powers the city state of Florence had a population of just 50 000 which is little bigger than Barnsley or Basingstoke. Yet Florence was one of the largest cities of the renaissance and was almost twice the size of cities like Vienna, Prague and Barcelona4. The medieval city was also dense, covering a fraction of the land area of a modern town of similar size. This compactness of built form created the tight urban streets and crowded buildings that we enjoy in historic towns such as Chester and York. The density was partly the result of city walls which restrained growth. But as Hoskins5 has shown, even unwalled towns and cities with no constraints on growth were remarkably dense. It has been suggested6 that this density resulted from the needs of travel by foot which undoubtedly played a role in the compactness of great cities like London. It may also have been that compact development was driven by a need to conserve the surrounding agricultural land on which the city relied for its food. These arguments have all been explored at length but they do not hold the whole answer. Most pre-industrial cities were built at far greater densities than can be explained by physical constraints, the needs of travel by foot or the protection of agricultural land. There were other forces at play which go to the heart of the nature of cities and our inability to recapture their character today – this is what we explore in this book.

Why is it that the most remote farmhouse is built so that it abuts directly onto the only road for miles? Why is it that remote settlements surrounded by acres of seemingly unused land are built so that their houses almost fall over each other? It seems that historically there was something deep within the human consciousness which sought companionship and security. We could imagine this dating back to the earliest encampments clustered around the communal campfire. Is it too far-fetched to imagine the tents becoming permanent shelters and the camp fire becoming the town square? Once the unseen dangers of the surrounding wilderness had been overcome the pattern of human settlement had been established.

The ideal compact city? Siena is the archetypal compact city. Despite the fact that it was built entirely without the aid of planners and urban designers it has been mined for inspiration by generations of urban professionals

However the need for human contact does not entirely explain the density of early settlements. Whilst fear of the wilderness may have been the initial motive this would soon have been combined with economic and political forces. It is likely that, in those early encampments, the tents nearest the fire would have been occupied by the chief and the most important members of the community. Here they would be close to the warmth of the fire and to the focus of community life and decision making. The lower status members of the community would have been relegated to the outskirts of the camp, vulnerable to attack and cut off from the seat of power and status. Since humans have always aspired to improve themselves, it is reasonable to assume that the citizens of those early encampments would have aspired to be near the camp fire, both for the benefits that it would bring but also as a symbol of their status and position.

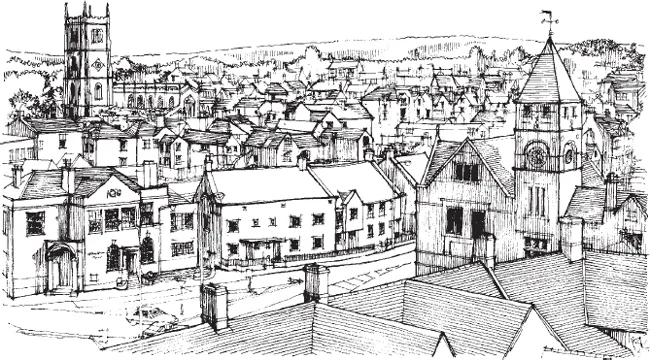

The UK compact city? Fine historic environments are not only to be found in Italy. Many UK market towns like Calne in Wiltshire have equally attractive and popular environments

It is not hard to imagine this process transferred to the earliest cities. As Robert Fish-man has described in Bourgeois Utopia7, the dynamic of the pre-industrial city meant that the centre of the town was the place to be. The richer you were, and the more status and power you had, the nearer to the centre you sought to live and work. The elite of the town, the merchants, nobles, church men and administrators would jostle for the best locations at the centre of town, much as the prime retailers like Marks & Spencer do in modern shopping centres. Just as in a shopping centre, this demand for the best location would have increased land values so that central areas also became the most expensive and the most profitable. The density of the pre-industrial city is the result of this demand for central sites. The competition for land meant that every available site would be developed to its maximum potential so that buildings became higher and more closely packed. Remember that in these early cities the merchants generally lived over their business, as indeed did many of their employees, so that pressures were intense. An extreme example of this can be seen in the 2000 year old high-rise buildings in the Yemen.

In these ancient towns there was a gradation in social status as one moved away from the centre. The poorest people and the dirty or marginal uses were pushed to the edge of the town, often outside the protection of the city walls. Indeed the term ‘suburb’ was originally coined as a disparaging expression meaning literally ‘less than urban’. Wherever they lived the citizens were united by a desire to move closer to the centre of city and thus the focus of power and commerce. The poorest denizen of the suburb would covet the neighbourhoods within the city walls. The artisans within the walls would covet the middle-class areas nearer the centre and the middle classes would aspire to a location on or near the town square. What is more, this would happen in towns where one could walk from the centre to open countryside in less than twenty minutes.

The shatter zone: A figure ground plan of Barnsley in Yorkshire today. This shows the structure of a dense medieval town surrounded by a zone of ill-defined space which separates it from the surrounding residential development. This space has been described by Llewelyn-Davies as a ‘shatter zone’ where considerable capacity exists for new development

In Manchester there is a sign on a building on the southern edge of the city centre which proclaims the ‘Boundary of the Township of Manchester’. Beyond this is the Gaythorne area, an old industrial quarter – now converted to housing – that for many years was an arc of old industry encircling much of the city centre. Such industrial areas can be found in many modern towns and cities such as on the plan of Barnsley (above). They mark the line of the original poor suburbs. They now lie sandwiched between the town centre and the inner city and yet have a quite different character. These are areas that have always been impoverished and have often been swept aside as the line of least resistance for railways and ring roads.

This is not to say that suburban trends did not exist in the pre-industrial city. As early as Elizabethan times there was concern about merchants moving out to the country, no doubt aping the landed gentry. However this was often based on single houses well beyond the poor suburbs and the houses tended to be used as weekend retreats. This is similar to the ‘dacha’ tradition still common in many eastern European countries. In some cases these weekend retreats would be transformed over time into the main family residence with the merchant commuting into town for business. This trend however remained relatively insignificant until the advent of the Industrial revolution.

The industrial city

The picture of growth in the pre-industrial city is a mirror image of modern Anglo-American settlements. The Industrial revolution placed such intense pressures on the traditional city that it reversed the polarity of settlements. In the modern Anglo-American city, status is measured not by how close to the centre you live, but by the distance that you can put between yourself and the perceived squalor of urban life. In the modern Anglo-American city (we will turn to the continental experience in a short while) the pressure for development is not in the centre but at the periphery. This has been the case with housing development for many years but in the last part of the 20th century it became true of all manner of activity. Town centre shopping declined as we switch our allegiance to the suburban supermarket or out-of-town shopping centre. The newspaper industry has largely abandoned Fleet Street for Docklands. Staff in central office districts have been decanted to peripheral business parks and urban cinemas have succumbed in the face of the multiplex.

Many reasons have been put forward for this dispersal of activity. It has been attributed to increasing mobility, initially due to commuter railways but more recently and more potently to the private car. It has been put down to changing retail and business needs which cannot be accommodated in congested urban areas, to the workings of the land market, and to demographic change. All have played their part; however at its heart this trend of ‘counterurbanization’ is driven by the same forces which drove urbanisation in the early cities, it is just that today these forces are working in the opposite direction.

The pre-industial city: Green's map of Manchester from 1794. The structure of the pre-industrial city in Britain was similar to the Italian cities that we admire today

Fishman suggests that perhaps the first true suburb was Clapham in London where the Evangelicals, led by Wilberforce, sought to protect their families from the evil influence of the city in the latter half of the 18th century. Clap-ham was a development of the earlier ‘dacha’ trend but was conceived from the outset as a suburb around Clapham Common intended to provide the main family residence for its occupants. It represents an important step in the separation of home and family from work and commerce. As such it was an influential model for Victorian family life which was to take such a hold later in the century.

The next step in Fishman's history of the suburb – or Bourgeois Utopia as he called it – took place in Manchester. This is significant, because whereas the Evangelicals were escaping from the traditional city, in Manchester the traditional city was being swamped by the Industrial revolution and something quite different was happening. Before the Industrial revolution the form of Manchester was similar to many medieval towns, as can be seen from Green's map of the city (above previous page) published in 1794. The dense form of pre-industrial Manchester was the result of the same forces of concentration which shaped the Italian hill town. For the early years of Manchester's industrialisation it maintained this traditional shape with density increasing towards the centre and the most affluent merchants living in areas like Moseley Street, Fountain Street, King Street and St. Anne's Square in the heart of the city. However the cotton mills which came to dominate the city required large amounts of labour and the city attracted rural migrants in vast numbers. As H. G. Wells said, this process turned cities like Manchester into ‘great surging oceans’ of humanity as documented by the plans in the introduction to this book.

The terrible conditions in the early industrial cities have been well documented elsewhere. Our concern here is the catalytic effect that the Industrial revolution had on the British city. The phenomenal growth of population and industry in cities like Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool and Sheffield stretched the capacity of the traditional city beyond b...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Case studies

- Dedication

- The authors

- Acknowledgements

- Preface to the 2009 Edition

- Preface to the 1999 Edition

- INTRODUCTION

- PART 1: THE ORIGINS

- PART 2: THE INFLUENCES

- PART 3: THE SUSTAINABLE URBAN NEIGHBOURHOOD

- Epilogue

- Index

- Notes and References

- Images and Illustrations