- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In a perceptive analysis of diverse source material, the essays of the late Uriel Tal in this volume uncover the dynamics of the secularization of religion, and the sacralization of politics in the Nazi era. Through a process of inversion of meaning, concepts such as race, blood, soil, state, nation and Führer were brought into the realm of faith, mission, salvation, sacredness and myth, thereby acquiring absolute significance. Within this Nazi worldview, the Jew epitomised the arch enemy, both as a symbol and as the concrete embodiment of all that Nazism sought to negate: Western civilisation, monotheism, critical rationalism and humanism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

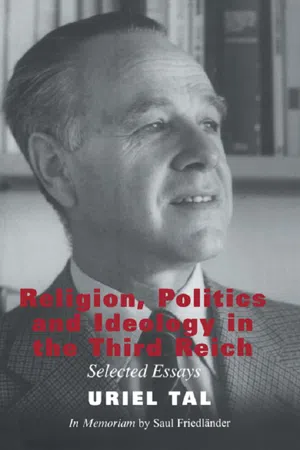

Yes, you can access Religion, Politics and Ideology in the Third Reich by Uriel Tal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Violence and the Jew in Nazi Ideology

There can be no discussion of violence in Central and Western Europe in the modern era without reference to the Holocaust. While this paper does not discuss the violence of the Holocaust per se, its focus is the conceptual framework that was created by Nazism and consequently helped to prepare the ground for the Holocaust.1

The semantic and ideational meaning of the concept of ‘violence’ has been defined by some of the leading ideologists of Nazism,2 such as Carl Schmitt, Ernst Forsthoff, Ernst Rudolf Huber, Ernst Krieck, and Ernst Jünger. According to Jünger, ‘violence’ (Gewalt) is ‘the transformation of strength into that political power (Macht) that motivates history …’.3 By ‘strength’ Nazi ideologists meant the internal power to resist external impact, influence, stress, pressure, or force. Strength was understood in terms of a personal inner power often articulated in terms derived from pietistic language. We see this in Krieck – ‘… innere Kraft die sich in dem innersten unserer Seele regt [inner strength that stirs us at the core of our soul]’ – or even more so in Ernst Jünger – ‘… ein Machtwort erginge in meinem Innwendigen an mich [a mighty message befell me in my inwardness] … und meine Seele entflammte [and my soul took fire] … in Kämpfes Ungestüm [in the violence of struggle] …’.4 Strength was understood as a form of one’s individual solidity, a kind of power stemming or emerging from one’s individual faith, conviction, or integrity; it was a certain kind of firmness, a form of moral or intellectual courage. Violence, or might, on the other hand, was considered the result of the transmission of strength from the individual to society, from man to the citizen, from society to the state, from the nation to the race, from the state to the Reich, and from the Reich through the party to its embodiment, to its highest, purest realization, its incarnation in the Führer.5

Therefore, violence did not necessarily or exclusively mean simply the use of brute force. Of course, it goes without saying that this kind of explicit, overt force, mainly in terms of ‘political might’, was one of the main manifestations of Nazi violence from its very beginnings. Carl J. Friedrich made this clear by enumerating some of the main characteristic features of totalitarian regimes: the predominance of an official ideology covering all vital aspects of man’s existence; the rule of a single political party passionately and unquestioningly dedicated to the ruling ideology; a technologically conditioned almost total monopoly of the control of all means of power, including mass communication or education; and a system of terroristic police control often methodically exploiting scientific psychology or sociology.6

However, violence as an integral part of the Nazi ideology and regime as a whole was meant to be applied rather indirectly. From its very beginnings, among the Free Corps and the Schutz und Trutz Bund during the first years of the Weimar Republic,7 as well as among its first student organizations,8 and more so later with the establishment of the Third Reich,9 Nazism intended to develop, groom, educate, and mold a new type of man, a man who did not need the power of the police or any other kind of Anwendung von Zwang (‘application of coercion’) to make him conform to the norms of the state or of society. The type of person Nazism tried to create was one who would demand of himself to act, think, feel, and believe according to what the regime expected of him, or according to what he expected the regime might expect from him. The entire complex of ideological and normative expectations applying to a member of the Aryan race was to be internalized and acted upon by the individual as a matter of course, lest he lose his peace of mind. In the long run, instead of exercising violent power by means of police coercion, Nazism intended to indoctrinate its youth so that no external violence would be needed in order to ensure the faithfulness of the German, or, more precisely, his total identification with the state, the race, the Reich, and their culmination and essence: the Führer.10

This complete identification with the totality of the Reich indicates the deeper meaning of violence in the Nazi era. Ernst Krieck emphasized that instead of the use of police power, the political philosophy of Adam Müller was to be ‘… imprinted on the mind of our youth, for according to Müller the state means: “… die Totalität der menschlichen Angelegenheiten, ihre Verbindung zu einem lebendigen Ganzen [the totality of human affairs, their binding into one living whole] …”’.11 Similarly, Ernst Forsthoff ’s definition of the Totalität des Politischen was accepted by many Nazi youth leaders as ‘… the essence of the inner strength … typical of the new Germanic man’.12

FREEDOM THROUGH TOTALITARIANISM

Against this background let us now concentrate on analyzing a number of Ernst Krieck’s lectures, some of which are as yet unpublished.13 While in the final years of the Third Reich the authorities and party were critical of Krieck,14 in the 1920s and when the Third Reich was established he was a recognized guide for young intellectuals, mainly products of the Nazi student unions of the Weimar Republic, and also for teachers, educators, and SS Leaders. In one of his most important lectures, apparently delivered in 1932 at a meeting organized by SS Obersturmführer Johann von Leers, who was once ‘Schulungsleiter in der NSDSt. B. Reichsleitung’,15 Krieck explained that the concept of violence–might signified ‘freedom’. In style and content this resembles the first part of his book Völkisch-politische Anthropologie, Part I ‘Die Wirklichkeit’ (‘The Reality’), especially the section entitled ‘Das völkisch-politische Bild vom Menschen’ (‘The Folk-Political Image of Man’) (Leipzig, 1936, pp. 42–119).

Thus, according to this philosophy, the totalitarian regime that a dictatorship controls does not lead to a negation of human freedom but to its realization. Political totalitarianism is the guarantee of freedom, for in a system in which politics encompasses all of life the individual man is free of society from various points of view:

a) According to the Carl Schmitt school, said Krieck, social life is composed of dichotomies and antitheses – friend–foe, war–peace, resolution–argument, healthy naturalism–degenerate religion, strength–weakness, bravery–cowardice16 – but the power of a dictatorship protects man from stumbling into such bipolarities and protects him from the fear and dread with which constant confrontation of choices burdens him; in particular, dictatorship releases man from the negative extreme of the antitheses, from foe, weakness, cowardice, isolation, individuality, and degeneracy. Political totalitarianism is therefore a redeeming force, saving man from the constant fear of forces that are his opposite, that are foreign to him or endanger his existence.

b) Society is composed of masses and consequently of violent forces which dominate and oppress the individual; in a political regime based on dictatorial power, however, the individual attains his freedom on the one hand by being released from the mass and on the other by identifying with the political elite headed by the Führer. In a democratic order man is subject to ‘… Die Macht der Öffentlichkeit [the power of the public] … im totalen Staat befreit der Führer den Menschen von den Massen, von der bedrückenden Öffentlichkeit, von der degenerierenden Intellektualisierung des wahren Lebens, vom Parlamentarismus [in the total state the Führer frees man from the masses, from the repressive public, from the degenerating intellectualization of true life, from parliamentarism] …’.17

c) Society confronts the state and enslaves the individual in this struggle against the state, as exemplified by liberal society, which binds the individual to a parliament–party struggle and thus deprives him of responsibility for himself; responsibility is given to the parties and the parliament, which are no more than a sort of conglomeration of egotistical amorphous forces, narrow-minded and lacking public responsibility – a sort of sum total of the mass, which is faceless, characterless, unrealistic, and aimless. The power of a dictatorship, however, protects the individual from the Leviathan nature of this society, primarily by creating an identity between society and state by means of a process known as totale politisierung aller Sozialprozesse (‘total politicization of all social life’).

d) Society places man in a situation of ‘orphanhood’ from any authority, while the power of a dictatorship provides man with authority, bestows authority upon him, spreads the wings of authority over him, and thus releases him from orphanhood, from isolation, and, to a great extent, from license as well.

e) In Western democratic society man is abandoned to economic forces which for him as an individual are arbitrary since as an individual he has no control over them. The power of a dictatorial regime, however, controls the economy as well, and thus man’s very identification with that power and his surrender to its authority makes him a party also to the economic factors operating in the state. On this point, Krieck no longer sang paeans of praise to the Gottfried Feder school, as expressed mainly in Feder’s Der deutsche Staat auf nationaler und sozialer Grundlage (‘The German State on National and Social Foundation’) (Munich, 1931, 5th edn), as he had done earlier. Now that the Feder school was no longer acceptable to the regime, Krieck praised the economic laws aimed at strengthening the position of capitalists and heavy industry, among them the ‘Gesetz über Betriebsvertretungen und über wirtschaftliche Vereinigungen’ (‘law concerning business representation and economic associations’), passed early in 1933,18 and the ‘Gesetz über die Einziehung volks und staats-feindlichen Vermögens’ (‘law concerning the confiscation of property which is hostile to the state’), passed at the end of that year.19 Here too Krieck stressed that the essence of these laws, dealing with labor relations and production, was the liberation of the working man from the particularist interests of what he called ‘miserly social pressure groups’, bestowing upon him real freedom by the identification of his particularistic interests with universal interests of the state, the race, the party, the Reich, and the Führer: ‘Freedom means the liberation of man from himself through total identification with the general will, which is embodied in the Führer …’ 20

This ideology, the main point of which is the attainment of individual liberty through identification with the general will personified by the Führer, still had several diverse trends in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Ernst Jünger represented the individualistic, or perhaps rather aristocratic, position in that he stressed that the citizen should refrain from completely annulling his individual will before the general will embodied in the Führer. If he does so, Jünger said, he will be incapable of blending with the general will, through his own decision and desire. Just as there is some modicum of willing devotion or conscious self-sacrifice epitomized in the battlefield, in war, or, as Kurt Ziesel said, ‘in creative war’ (vom schöpferischen Kriege), it is desirable to have room for it in the political regime of a totalitarian state. The ideal totalitarian regime is one which allows the individual his individuality so that it can combine with the general will. This is true, claimed Jünger, in regard to the concept of the omnipotence of the state, for if the state chokes off all individual will, it will also choke off the individual’s will to surrender himself to that Omnipotenz. On the other hand, Ernst Forsthoff as well as E.R. Huber contended that ‘die totale...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- In Memoriam by Saul Friedländer

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Violence and the Jew in Nazi Ideology

- 2. ‘Political Faith’ of Nazism Prior to the Holocaust

- 3. On the Study of the Holocaust and Genocide

- 4. Structures of German ‘Political Theology’ in the Nazi Era

- 5. Law and Theology: On the Status of German Jewry at the Outset of the Third Reich (1933/34)

- 6. Religious and Anti-religious Roots of Modern Anti-Semitism

- 7. On Modern Lutheranism and the Jews

- 8. Jewish and Universal Social Ethics in the Life and Thought of Albert Einstein

- Index