![]()

1 The sources

The sources of information for the Roman cavalry are the same as those commonly used for any history of the Roman army as a whole. The evidence is sometimes fragmentary and therefore incomplete for any period of the Empire, and all the available information should anyway be used with caution.

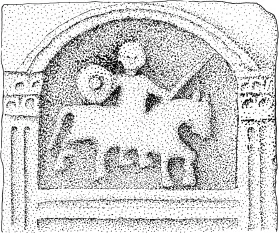

Documentary evidence includes the writings of the ancient authors, military records and letters on papyrus or writing tablets, and inscriptions on stone, such as tombstones, altars and permanent records of special events, for example Hadrian’s speech to the Numidian army, set out as a huge inscription at Lambaesis. A tombstone often conveys details of the deceased’s career and also a ‘portrait’, and is therefore just as much a document as a papyrus or the text of an ancient writer. The reliability of sculptural evidence is questionable (Fig.1), but artistic representations of cavalrymen and their horses are so abundant all over the Roman Empire that they cannot be ignored. In addition to the documentary evidence, archaeological discoveries have revealed much about Roman forts and about the military equipment of the soldiers who manned them.

All these sources taken together can be used to reconstruct, tentatively, a history of the Roman cavalry. It is probably true to say that there are more questions than answers, and so the gaps in our knowledge can be filled only by speculation. If future discoveries reveal that any or all of this is wrong, the reader will no doubt make his or her own subtractions and additions.

Perhaps one of the greatest problems connected with the use of any of the aforementioned evidence is that the history of the Roman Empire stretched over both an enormous time-span and a large geographical area. The evidence from one or two provinces at a specific date is not necessarily relevant to the rest of the Empire, either at the same or at different times. Whilst it is important to try to evaluate what the ancient authors wrote about the Roman army, this can be misleading if it is not explained how far they are separated from each other by time and place. For example, if the information from the works of, say, Polybius, Josephus and Vegetius (Epitoma Rei Militaris) is lumped together without a cautionary word about when and why each of them wrote, the resultant composite picture of the army will be distorted if not false. Polybius was a Greek of the second century BC who observed the Roman army of the Republic. Josephus was a Jew who recorded in meticulous detail the army of Vespasian and Titus in Judaea in the AD 60s. Vegetius, writing in the fourth century AD, described how he thought the army should operate, and not necessarily how it did, in his day. Such a procedure would be much like trying to reconstruct a history of the English army using firstly the work of Ordericus Vitalis who wrote in the twelfth century about the exploits of William the Conqueror; secondly a few documents concerning the campaign leading up to the battle of Agincourt; and thirdly the musings of Marshal de Saxe, who wrote down his thoughts on how an army should be run in the 1730s (though the work was not published until 1756). It does not need to be said that such a project would be patently ridiculous, but the time-span was roughly the same as that covered by the Greek and Latin authors previously mentioned. Even if the invention of firearms is discounted, the changes which occurred in military operations between the twelfth and the eighteenth centuries could not be properly documented from such sparse and widely divergent sources. The Roman army also changed over the centuries and we are allowed merely a glimpse of it from time to time; the rest is obscure.

1 Tombstone of Silicius Catus, Oran Museum. Basing arguments about armament styles and breeds of horses on such sculptures clearly has its limitations. Comparison with more elaborate and (possibly) more accurate gravestones reveals the primitive style of Catus’ portrait, but it should be remembered that all the tombstones depicting Roman soldiers shared the same purpose, namely that of honouring the dead. (Drawn by K.R. Dixon.)

None the less, though the details of organization and equipment may have changed, there are certain broad principles that would have remained the same over several centuries. For instance, troops must be taught to work together and trained in the various manoeuvres and duties they are to perform. Horses have to be obtained, looked after and fed, and eventually disposed of. For this reason comparative evidence from other periods of history has been used in this book. Until roughly the Second World War, horses were indispensable all over the world in many walks of life, in transport and agriculture as well as warfare, therefore first-hand knowledge of horses was much more widespread than it is today. In this mechanized age the majority of people have no contact with horses, and are still further removed from cavalry and its use. The military manuals published by the British War Office up to the 1930s, and the works of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century soldiers who had direct knowledge of cavalry, can usefully supplement the sometimes scanty information that exists on the Roman mounted units. The problems faced by all armies until the age of mechanization were often quite similar. Communications, transport and supply, together with disease and accidents among men and animals, probably limited the activities of the Roman army just as much as any other, and it is of interest to compare how other armies dealt with such problems. It is unlikely, for instance, that in the provinces of the Rhine and Danube the grass grew any earlier or later for the Romans than it did for Marlborough in the first decade of the eighteenth century. Dependent as it is on supplies of fodder and forage, cavalry is sometimes restricted in its actions by seasons and locations. This is yet another reason why several provinces should not be studied together without sufficient differentiation between their geography and climate, which affect agriculture, transport and food supply.

Literary sources

Concerning ancient literature, all manuscripts are subject to the same dangers of miscopying over the centuries, and even worse, of complete loss of certain sections. The wonder is that so much has survived, and it is perhaps not surprising that there are so many uncertainties surrounding that which does. Even the authorship of some works is disputed. There are those who say, for instance, that Xenophon did not write The Art of Horsemanship and The Cavalry Commander. It is an opinion that should be noted but the finer details of the dispute are best left to classicists and philologists. The main points are that someone did write these two works; that they are very useful; and that Xenophon is as good a code word as any with which to identify them. The books concern the cavalry of ancient Greece, not the later Roman cavalry; and although the information is useful it should be remembered that Xenophon was concerned with how the cavalry should be organized. There were evidently many faults he would have liked to correct, and there is not infrequently a note of exasperation in his writings. But documentation of common failings is useful in itself.

For yet other works not only the authorship but also the date is disputed. Hyginus’ book, formerly known as De Munitionibus Castrorum and more recently corrected to De Metatione Castrorum, is often referred to as pseudo-Hyginus, because it is not certain who was responsible for it. This in turn means that it is impossible to date it accurately: it has been placed variously in the reigns of Domitian, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, and in the third and fourth centuries. The only certain fact about it is that it concerns a campaign on the Danube, when the Emperor was present, accompanied by his entourage.

The documentary sources can be divided into two broad categories, consisting of those in which the author recorded his own observations or first-hand knowledge, and those which were compilations, usually narrative histories, that owe their origin to a variety of sources, not all of which can be identified.

In the first category Polybius and Josephus have already been mentioned. They were not Romans and they recorded their observations of the army at a particular point in time. If there were facts which they misunderstood, or even deliberately misrepresented, these are difficult to identify at this distance in time. Such a possibility, combined with modern misreadings, precludes unrestricted use of such sources. Perhaps more reliable are Caesar’s commentaries on the Gallic and Civil Wars. However much it may be possible to level at him the accusation that the works were undertaken primarily for self-aggrandizement and political advancement, the places, personalities and events of his books are probably not overly distorted. The fact that he was able to record the names of officers and soldiers who had distinguished themselves suggest that he used military records compiled at the time, or that he kept notes himself, or both. In any case these books provide first-hand experience of late Republican army practice and the problems faced on campaign.

Arrian was another author who wrote from his own experience. He was a friend of Hadrian and his work includes both the description of the battle order employed by him against the Alans, a tribe from south-east Russia who threatened the eastern Roman provinces while he was governor of Cappadocia, and the Tactica. The latter specifically concerns cavalry and is therefore extremely valuable as a source, but it is once again restricted to one specific time and place, and it is not certain how widely applicable it might have been. On the whole Arrian has a good reputation as a plain and straightforward writer, who tried to use the most reliable sources of information.

Narrative histories such as Tacitus’ Annals and Histories, and the books of Appian and Cassius Dio, can provide information on how cavalry was used, and illuminate administrative details of army life which are not accessible from epigraphic or papyrological sources. The Romans kept a central records office in Rome (the Tabularium), where official archives were deposited, and there may have been similar record offices in each provincial headquarters. It is not certain how far writers would be allowed access to such information. Perhaps it depended largely upon circumstances and personal connections. In general, it could be said that the authors quoted above are more reliable than, for instance, Suetonius, who wrote The Twelve Caesars, and those who were responsible for the Scriptores Historiae Augustae dealing with the later Emperors.

Military writers of the late Roman Empire include Vegetius, who wrote in the fourth century; Procopius whose work belongs to the mid-sixth century; and Maurice whose Strategikon may have been written about the end of the sixth century. These writers lived and worked at times very remote from the age of the late Republic and early Empire and it is to be expected that the armies they described would be quite different from what had gone before. Flavius Vegetius Renatus was not a soldier but a civilian official who had read widely. He is sometimes confused with Publius Vegetius Renatus who wrote Ars Mulomedicinae. Flavius Vegetius’ military manual, Epitoma Rei Militaris consists of four books classified by subject: recruits; organization; strategy; and fortifications. They are so packed with information that it seems wasteful to reject any of it, but Vegetius’ books were compiled from widely differing sources of all periods, without discrimination and sometimes without acknowledgement, making it difficult to assess the precise value of what he says.

Procopius’ History of the Wars seems to be based on somewhat better foundations. In this he tried to record events of which he himself had knowledge or he used information from eye-witnesses to try to arrive at the truth. He was clearly a supporter of Belisarius and in opposition to Justinian, with the result that another of his works, the Secret History, is less reliable because it was devoted to an attack on the latter.

The Strategikon is a military manual, the authorship of which is not definitely established but is usually attributed to the Emperor Maurice. It belongs to the end of the sixth or the beginning of the seventh century, and documents not only Byzantine methods of waging war but also contains information on the peoples against whom the Byzantines were fighting, such as the Lombards, Avars and Franks. Much of the work consists of sound common sense and covers general principles which to some extent may be applied retrospectively to the previous two or three centuries.

Sources for Roman law which have some relevance to the army are the Codex Theodosianus, dating to the end of the fifth century, and the Digest of Justinian, which came into force at the beginning of the sixth. The Codex Theodosianus of AD 438 is a compilation of earlier laws and enactments and contains material from the time of Constantine onwards. The Digest is composed of a much wider range of material, not laws but legal opinions, for the most part drawn from the works of writers of the second and third centuries. One of the most useful aspects of the Digest is that the original author is noted, so that it is possible to arrive at a better evaluation of the information. The leges militares of Ruffus are a compilation of laws found in a Byzantine collection called luris Graeco-Romani by Johannes Leunclavius, published in 1596 (Brand 1968, xxxii). The author Ruffus is unknown; he may possibly be identified with Sextus Ruffus (or Rufius) Festus, who was a provincial governor under Valentinian II. If this is so, his wide experience of military matters would have given him the basis for his compilation of laws (Brand 1968, 138). It has also been suggested that whoever wrote the laws may be the same person as the author of the Strategikon, mentioned above as attributed to the Emperor Maurice. In this case, Ruffus may have been a military officer serving under Maurice. The laws themselves do not appear to have been merely extracted from the Digest, the wording is different and there is reason to think that they derive from an independent source (Brand 1968, 136–41). In the present work, however, the name cited in connection with these laws is Ruffus (despite its doubtful authenticity) because it is a convenient and distinctive label.

Specialist literature not primarily concerned with the cavalry but which has some bearing on it, includes the agricultural works of Cato (Marcus Porcius), Varro and Columella, and the veterinary authors such as Vegetius (Publius) and Pelagonius. Cato wrote his De Agricultura in about 160 BC and although it is not much concerned with horses he did list fodder crops available at his time. Varro and Columella whose works date to roughly AD 37 and AD 60–5 respectively, dealt with farm animals in more detail, giving information on feeding, housing and breeding horses. Though they both acknowledged the importance of horses for warfare, they kept to their civilian farming themes. The veterinary authors’ work can be properly evaluated only by a trained specialist with veterinary knowledge and also deep experience of horses. In the absence of these two qualities, it is merely possible to repeat what the books contain. Vegetius derived most of his information from other sources, notably Pelagonius, who in turn had used Columella’s work. The result is a compilation not based on direct veterinary experience.

Inscriptions

The many inscriptions that have survived from the Roman Empire can provide details about army units and individual soldiers. Inscriptions from forts naming the units that built them and/or occupied them can help to distinguish ‘cavalry’ forts, but this useful information is quite rare and the identification of forts intended for cohortes peditatae, cohortes equitatae and alae is not as straightforward as it may seem.

Altars and tombstones provide information about individual soldiers, sometimes merely their names but they often include further details. On some altars, the soldiers related their reasons for dedicating them to particular gods or goddesses, and occasionally they added the names of the consuls of the year, from which it is possible to establish an exact date. On tombstones it is usual to find the soldier’s name, rank and the unit he was serving in at the time, sometimes with an account of other units in which he had served, his age at death and his length of service. Some men are described as veterans, others presumably died while still in service. Only very rarely is the cause of death included on the funerary monument.

One inscription which is often quoted in connection with the Roman cavalry is Hadrian’s Adlocutio, or address to the army of Numidia, which he gave at Lambaesis in AD 128. The legionaries and auxiliaries put on a display for the emperor which he described and praised in his speech. Much of it survives, inscribed on a column (CIL VIII 18042 = ILS 2487; 9133–5). The valuable information it provides about the equites legionis and the exercises of the cohortes equitatae and alae will be discussed in the relevant contexts.

Pictorial sources

The sculptures on numerous Roman monuments vary enormously in style and competence of execution, and should not be used as evidence to support any theory without a note of caution. Some monuments, such as Trajan’s Column, have been quoted as authentic depictions of the soldiers, their equipment and horses. This is somewhat dubious: the very perfection of the human figures and the horses ought to warn against the acceptance of the sculptures as realistic portrayals. Some of the funerary monuments to be found in museums include a wealth of detail on horse trappings and so...