- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Electronics for Service Engineers

About this book

Electronics for Service Engineers is the first text designed specifically for the Level 2 NVQs in Electronics Servicing. It provides the underpinning knowledge required by brown goods and white goods students, reflecting the popularity of the EMTA white goods NVQs. It has also been written in the light of the new EEB / City & Guilds Level 2 progression award (RVQ) for brown goods and commercial electronics, dubbed 'son of 2240', and the existing 2240 part 1.

The wide ranging experience of the authors makes this a readable book with much relevance to the real-life challenges of the service engineer. From simple mathematics and circuit theory to transmission theory and aerials, from health and safety to logic gates and transducers, the complete range of knowledge required to service electronic and electrical equipment is here. This practical emphasis makes the book ideal for existing service engineers seeking to gain an NVQ.

Numerous questions and worked examples throughout the text allow readers to monitor their own progress, and provide practice for C&G tests.

Joe Cieszynski and Dave Fox have a wide mix of experience, both in the field and workshop working on TV and audio, and teaching electronic servicing and security installation at MANCAT. Joe writes regularly for Television magazine.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Safe practice in the workplace

Every year numerous accidents, both minor and major, occur in the workplace. Yet in many instances these accidents could have been avoided if individuals had followed basic health and safety procedures, which quite often are nothing more than plain common sense. All too often people are injured because they, or someone around them, have either become complacent, have made an error of judgement, have been reckless, or have cut corners.

In many countries employers and trade unions have laboured to improve working conditions in order that industrial injuries are cut to a minimum. For many years in the UK the various Factory Acts, enforced by factory inspectors, have served to provide codes of practice that are designed to protect not only the employers and employees, but also the general public.

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 (HASAWA) expands on the provisions of the Factory Acts, and provides a comprehensive legal framework designed to promote high standards of health and safety in the workplace.

Of course, an act is no use unless it is enforceable. The HASAWA is enforced by a nationwide team of inspectors who are appointed by the Health and Safety Executive. These inspectors are entitled to enter a premises at any reasonable time, collect any evidence they believe relevant in cases where a breach of the Act is suspected, and inspect any relevant documentation. Where an accident has occurred, the inspectors will investigate the conditions surrounding the incident, and the executive may take action and prosecute anyone whom they consider may have caused the accident through a breach of the Act.

In 1980 the Notification of Accidents and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (NADOR) was introduced. These regulations require employers and the self-employed to notify the local Health and Safety Executive office (usually within the local environmental health department) of any serious accidents, injuries, or cases of disease. In 1986 these regulations were superseded by the Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations (RIDDOR).

The HASAWA aims to involve everyone in matters concerning health and safety, whether they be employers, employees, self-employed, site/building managers, equipment and material manufacturers, or the general public. The scope of the Act is very wide as it encompasses all working conditions and environments, i.e. office, manufacturing, engineering, construction.

The Act states clearly the responsibilities of both the employer and the employee. These are summarised below; however, this chapter will deal mainly with those areas that appertain to electronic engineering.

Employer responsibilities

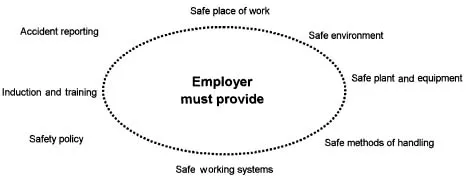

Figure 1.1 summarises the responsibilities of the employer. Failure to provide any of these could lead to prosecution, especially if it were proven that an accident had occurred because one or more of these provisions had not been made.

Figure 1.1

For the electronics servicing industry, providing a safe place of work generally means providing a building that is suitably maintained and is free from hazards.

A safe environment means having a temperature that is comfortable to work in, and an atmosphere that is clean not only from dust but also fumes, odours, fungi, etc. It also includes provision of washing, sanitation and first aid facilities. The reference to toxic fumes has become more applicable to electronic servicing workshops with the introduction in 1994 of the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health regulations (COSHH). Although these regulations cover a wide range of substances, in electronics it has altered the way large-scale soldering/de-soldering is performed. For many years it was acceptable to solder with a hand-held iron and simply duck out of the way of the high lead content smoke. Under COSHH the soldering equipment must have an extraction facility to prevent the atmosphere in the room from becoming toxic. In practice many inspectors look at this realistically, and do not insist that a small workshop with occasional soldering taking place should have extraction equipment. However, any premise where constant soldering takes place must be suitably equipped.

The COSHH regulations also affect the disposal of batteries. Throwing batteries into a waste bin means that they will more than likely end up on an open cast refuse tip where the toxic chemicals will eventually seep into the earth. All employers must make provision for correct disposal methods, which generally involve a plastic container specifically designated for battery disposal. This container can be emptied separately by the local authority cleansing department (for a fee), or in the case of lead/acid batteries, arrangements can be made with a recycling company for them to be collected.

Although engineers are usually expected to provide their own tools, the employer must ensure that all plant and equipment used at the place of work are safe. For a workshop, plant could be interpreted as benches, storage racking, trolleys, etc. Equipment would be test equipment, power tools, etc. Benches must be well maintained and at the correct height, whilst test equipment is maintained and PAT tested annually. All power tools must be safe, and have the correct safety guards fitted and working.

Employees must not be expected to move heavy items unaided. The employer must provide appropriate lifting and transportation equipment. In some cases it may be necessary for two people to be made available to move or transport an item.

Companies must devise safe working systems, which are procedures designed to minimise the risk of accidents. Once devised, these systems can be written up as a company safety policy. Policies such as this are not intended to be static, but dynamic. For example, when accidents occur, they will be investigated and the procedures modified if necessary. The employer must ensure that all employees are made aware of the safety policy, and any subsequent modifications to it. This should form part of an employee’s initial induction and ongoing training. Examples of safe working systems are provision of protective clothing for certain tasks, provision of appropriate staffing levels for specific jobs, suitable warning notices of hazards or hazardous areas, and provision of clearly marked first aid facilities.

Under RIDDOR, employers’ accident reporting involves informing their local health and safety inspectorate immediately following an accident resulting in death or serious injury. Incidents of a lesser nature may be reported within a certain length of time. The employer must also provide a reporting procedure for employees.

Employee responsibilities

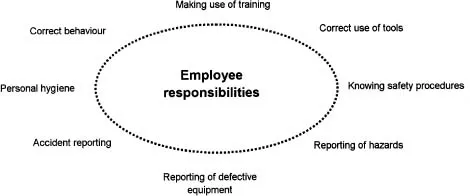

These are summarised in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2

Making use of training. Safety policies can only be effective when each individual takes responsibility for their own actions, and ensure that they are observing safe working practice. All engineers are taught safe practice, and they must be aware that they may be held responsible for any accidents that occur should they fail to adhere to these practices. Such practices include correct use of tools and equipment, isolation of equipment from the mains voltage supply when carrying out certain jobs, not working whilst under the influence of alcohol or drugs (including certain prescribed drugs), wearing appropriate clothing, and wearing safety clothing where necessary.

Each employee must make it their business to familiarise themselves with the company safety policy, and to know the safety procedures.

Hazards and hazardous situations can arise at any time, and employees must make it their business to report any hazards to the appropriate person immediately. A hazard can be anything that could cause an accident, e.g. a loose carpet, defective storage racking, a blocked fire exit. Such things are so commonplace they can become a fact of life and hence ignored, but they are all accidents waiting to happen and should be reported so that they can be rectified.

Equipment and tools can be in use all day and every day, and this constant wear and tear often results in faults and defects that present potential hazards. Frayed mains leads, loose mains plug connections, broken casing on power tools; all of these defects must be reported. In a larger company there should be a reporting procedure where the fault would be reported in writing, and the employee finding the defect would attach an official warning label to the tool or equipment. However, even within a smaller company a defective item should be labelled to warn other employees of the defect.

All accidents must be reported in writing. Where a minor injury has occurred, the employee concerned must fill in details of the injury, and how it occurred, in the accident reporting book provided by the company. Where the injury is of a more serious nature and the employee is perhaps unable to give details, statements must be taken from any witnesses, and the employer must report the incident to the Health and Safety Executive office.

The employer is required to provide sanitation and cleaning facilities, but it is the employees’ responsibility to make use of them. Personal hygiene in the workplace is very important if one is to avoid illness, skin irritations, etc.

Practical joking, horseplay, or an over-casual attitude has no place in a workshop or any other place of work. All employees are required to behave appropriately, and may be held criminally responsible for any accidents resulting from incorrect behaviour.

On-site servicing

It is relatively easy to create a safe environment within a designated workshop, but electronics servicing engineers are frequently required to service equipment on site, thus introducing all kinds of safety issues. For example, live circuits may need to be exposed in the vicinity of the general public, and in a domestic situation this may well include children. In such circumstances, how can an engineer be certain that he can control the environment? What might a child get up to whilst the engineer is at his vehicle looking for a part?

Other hazards are faulty electrical wiring within the building that could render the equipment unsafe to work on, lack of mains isolation transformers (which will be discussed later in the chapter), confined working space, and insufficient light. All of these must be taken into consideration by the engineer because ultimately the engineer is the one who is responsible for safety during the servicing operation.

If there are any doubts about safety whilst carrying out a task on site, the engineer should cease working and make alternative arrangements such as have the item of equipment brought into the workshop, return to the workshop for a complete working panel or mechanism, or, if these options are not viable, make arrangements with the customer to service the equipment when a safe environment can be created.

Electrical safety

Before looking at means of prevention of electric shock it is necessary to examine the effects of electricity on the human body, and the causes of electric shock.

All muscles are controlled by the brain via very small electrical impulses. When an external electrical current of a value greater than that generated by the brain passes through the body, it effectively takes over control of the muscles. There are three major consequences of this.

First, a current passing through the heart (which is its self a muscle) may cause it to cease its pumping action, the commands from the brain being overwhelmed. The person thus suffers from a cardiac arrest.

The second consequence may be that a person becomes ‘stuck’ to the live conductor. This occurs when a person touches a live conductor with their hand, and the polarity is such that the signal to the muscles in the hand is effectively saying ‘contract’. The hand now grabs the conductor and the person is unable to let go, even though they may try to do so; the small ‘let go’ command from the brain being totally swamped. Left in contact with the conductor, heat is generated and the person may receive severe burns, especially if the voltage is sufficiently high (>50 V).

The third consequence may be that, on touching the live conductor, the polarity of the current commands the muscles in the arm to reflex. The person appears to throw themselves from the conductor, although they have no control over this action. A danger with this is that there are no guarantees where the person will land, and serious physical injury may result.

I...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Safe practice in the workplace

- 2 The electronics servicing industry

- 3 Calculations

- 4 Science background

- 5 Electricity

- 6 Resistors and resistive circuits

- 7 Chemical cells

- 8 Capacitance

- 9 Magnetism

- 10 Semiconductors

- 11 Electrical components

- 12 Electronic circuit applications

- 13 Electronic systems

- 14 Logic circuits

- 15 Test equipment

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Electronics for Service Engineers by Dave Fox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.