![]()

Part One: Perspectives

The aim of this part is to discuss methodological issues surrounding the analysis of organizations in general and Olympic organizations in particular, review developments in the organization theory literature with a focus on structural formations and types and finally discuss approaches to event management in the context of mega project planning.

Defining the Scope of the Analysis

The approach adopted here is to conceptualize the organizational analyses presented in this book as a series of conversations (Clegg & Hardy, 1996) that relate to the (Olympic) organizations as empirical objects and organizing as a social process. In line with Clegg (1990) we start with the premise that organizations are empirical objects. By this we mean that we see something when we see an organization, but each of us may see something different.

As researchers, we participate in enactment and interpretation processes. We choose what empirical sense we wish to make of organizations by deciding how we wish to represent them in our work. How aspects of Olympic organizations are represented, the means of representation, the features deemed salient, those features glossed and those features ignored, are not attributes of the organization. They are an effect of the reciprocal interaction of multiple conversations: those that are professionally organized, through journals, research agendas, citations, and networks; those that take place in the empirical world of these organizations. The dynamics of reciprocity in this mutual interaction can vary: some conversations of practice inform those of the profession; some professionals talk dominated practice; some practical and professional conversations sustain each other; others talk past, miss, and ignore each other (p. 4).

With this conceptualization of analyses of (Olympic) organizations one can strive for reflexivity, by which we allude to ways of seeing which act back on and reflect existing ways of seeing. None is a more ‘correct’ analysis than any other: there are different possibilities. Like any good conversation, the dialectic is reflexive and oriented not to ultimate agreement, but to the possibilities of understanding of and action within the contested terrains (p. 5).

Plenty of homogenized textbooks exist which offer certainties enough for those who require them and converting the anxieties of their readers into easy recipes and conventions. For students reading this book who endeavour to understand the Olympic events’ organization and grasp the complexity of the interactions between the various agents and agencies involved the book provides a starting point. For those aiming to engage theory to understand practise there are conceptual frameworks that aid theorizing. For managers in Olympic organizations there is the opportunity to see the broader organizational picture, the interdependencies of the Olympic business setup and the challenges presented by the contexts within which this array of organizations is operating.

For Smith and Peterson (1988: pp. 47–48) definition of events of any kind have certain amount of elasticity in both space and time. Tentative boundaries defining an event could be placed around an exchange between individuals and organizations. The context, which would be an implicit but integral part of this event, would include things like the previous relationships between them, other occurrences in their respective work and personal lives, and the physical characteristics of the setting. Alternatively, an event could be defined as the entire history of the relationship between these two parties. If we choose the second perspective, the organization’s history as well as occurrences within the industry or the nation must be considered as the implicit context of the event. Thus, an ‘event’ comprised of various ‘occasions’ is constructed out of the information available to an observer, whether that observer is an actor or an ‘objective’ outsider. However, the imposition of boundaries around an event is not arbitrary, and it derives from what is actually done by the parties involved. The involved parties are seen as actually constructing ‘Gestalts’ or unified sets of perceptions, which may parallel the events constructed by observers. Similarly, Olympic events can be defined as the history of relationships between the Olympic Movement and the host city country.

Positivist and constructivist research paradigms are important in the sense that they can provide particular sets of lenses for seeing the social world.

The theoretical approach of the organizational analyses reported in this book is founded on the realization that the ability to analyse phenomena of various kinds in organizations depends on the adequacy of the theoretical schemes employed. Such theoretical schemes not only guided the search for significant relationships that exist in the organizational settings of Olympic organizations but also assisted in establishing the difference in the researcher’s eyes, between simply knowing of a phenomenon and understanding its meaning. As a consequence, the research efforts were aided by the substantive bodies of theories that are discussed in this part. Bedeian (1980) claims that theory serves both as a tool and as a goal. The tool function being evident in the proposition that theories guide research by generating new predictions not otherwise likely to occur. As a goal, theory is often an end in itself, providing an economical and efficient means of abstracting, codifying, summarizing, integrating, and storing information.

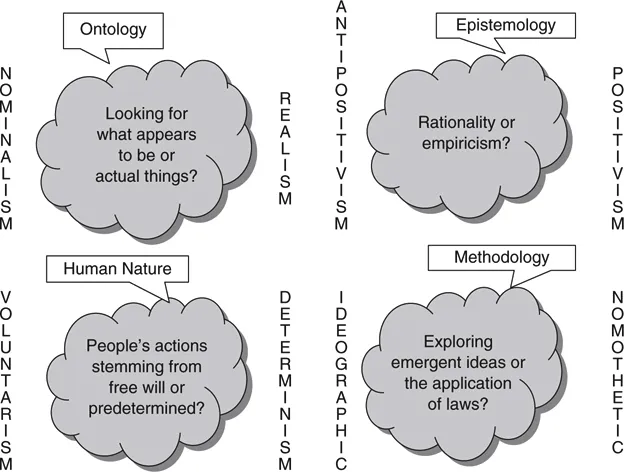

Before reviewing the emerging theoretical perspectives available to organizational analysts an attempt can be made to investigate how such perspectives can be mediated for purposes of inclusion and application. Morgan (1997) argues that the research possibilities raised by different theoretical perspectives need to be harnessed in order to yield the rich and varied explanations offered by multiple paradigm analysis. Like Morgan, Willmott (1990) is also concerned with paradigm plurality. Both examine Burrell’s (1996) scheme of competing paradigms, according to which social science can be conceptualized in terms of four sets of assumptions related to ontology, epistemology, human nature, and methodology (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Variety of assumptions about the nature of social sciences

Source: Adapted from Burrell (1996)

Willmott (1990) explores the possibilities for reconciling what Burrell (1996) regard as the irreconcilable features of these paradigms. He argues that the assumption of paradigmatic closure should be challenged by examining the attempts of Giddens (1979; 1982) to integrate subjective and objective paradigms.

The organizational analyses presented in this book have been concerned to move away from approaches based upon the dualism between action and structure, whereby a contrast is drawn between a structural perspective which specifies abstract dimensions and abstract constraints, to an interactionist perspective which attends to symbolic mediation and negotiated processes. Willmott (1990) argues that these procedures and perspectives which, used to be regarded as incompatible, must be incorporated in a more unified methodological framework.

It is important to note that the aim of the research undertaken within the organization theories perspectives was to provide a better understanding of the organizational characteristics and dynamics found in Olympic organizations. This was to be achieved through the development of analytically structured narratives which, as Hassard and Pym (1990) argue, link agents’ actions, structure, and context as they interweave within structural inertia, random events, contextual discontinuities, and significant changes in the environment.

Theoreticians have attempted to ‘fix’ the organizational world and by reducing its dynamics to a static classificatory system, imprison it. In this they have forced organizational analysis onto a procrustean bed on which it groans and squirms because it is not the right size to fit the cramping framework into which it is being pressed. Yet the forcing goes on. Each of the terms to be addressed below forces the subject into an understandable and simplifying framework. This after all is what science does. But we must realize that what every concept does is to exclude as well as include, ignore as well as concentrate upon, to consign to obscurity as well as bring into the limelight. Concepts stretch the point and nowhere more than in the concept of paradigm (Burrell, 1996: p. 646).

Morgan (1997) argues that by using different metaphors to understand the complex and paradoxical character of organizational life, we are able to manage and design ways that we may not have thought possible. His use of different metaphors can also aid identification of issues and areas of friction in organizations. The political metaphor for example, allows researchers to focus on the different sets of interests, conflicts, and power plays that shape organizational activities. Using it one can explore organizations as systems of government drawing on various political principles to legitimize different kinds of rule, as well as the detailed factors shaping the politics of organizational life. As regards the organizations as instruments of domination metaphor, the focus is on the potentially exploitative aspects of organization. The ways in which organizations often use their employees, their host communities, and the world economy to achieve their own ends, and how the essence of organization rests in a process of domination where certain people impose their will on others. An extension of the political metaphor, the image of domination helps understand the aspects of modern organization that have radicalized labour–management relations in may parts of the world. This metaphor is particularly useful for understanding organizations from the perspective of exploited groups, and for understanding how actions that are rational from one point can prove exploitative from another. Images of organizations can generate ideas and concepts that we can use for diagnosis and evaluation to understand organizations in specific settings.

This aspect of organization has been made a special focus of study by radical organization theorists inspired by the insights of Karl Marx and sociologists Max Weber and Robert Michels.

The negative impact that organizations often have on their employees or their environment, or which multinationals have on patterns of inequality and world economic development, are not necessarily intended impacts. They are usually consequences of rational actions through which a group of individuals seek to advance a particular set of aims, such as increased profitability or corporate growth. ‘The overwhelming strength of the domination metaphor is that it draws our attention to this double-edged nature of rational action illustrating how talking about rationality one is always speaking from a partial point of view. Actions that are rational for increasing profitability may have a damaging effect on employees’ health. Actions designed to spread an organization’s portfolio of risks, for example by divesting interests in a particular industry, may spell economic and urban decay for whole communities of people who have built their lives around that industry. What is rational from one organizational standpoint may be catastrophic from another. Viewing organization as a mode of domination that advances certain interest at the expense of others forces this important aspect of organizational reality into the centre of attention. It leads to an appreciation of Max Weber’s insight that the pursuit of rationality can itself be a mode of domination, and to remember that in talking about rationality one should always be asking the question “rational for whom?” ’ (pp. 315–316). The real thrust of the domination metaphor should be to critique the values that guide organization and the focus of analysis should be to distinguish between exploitative and non-exploitative forms, rather than to engage in critique in a broader sense.

It is argued (Bryman, 1988; 1989) that doing research in organizations poses particular challenges to researchers. There is a wealth of academic gossip about the false starts that are part of the everyday world of the social researcher. Researchers make mistakes and change their minds. The lack of guidance to some of the realities of social research that textbooks offer can be held partially responsible for these tendencies. In addition, one needs to consider the influence of funding bodies and gatekeepers.

There is a tendency to present research as though its origin and course are largely uninfluenced by external institutions. But such research may be funded and commissioned by external bodies and where research is conducted within organizations, gatekeepers have to allow the researcher access. Those who fund and those who provide access may seek to influence research very directly. Luck and serendipity in research also play an important role; being at the right place at the right time for picking up a number of important leads. The role of resources often surfaces in relation to very specific issues, such as the impact on sample size or the relative savings through the use of certain instruments in comparison to others. But they can also influence the climate in which research is done. The presence and absence of resources may constitute a key determinant of what is and is not studied not to mention how research is done. As regards the human resources involved in research it is important to note that there is often great fragility in research teams. They can easily deteriorate into hotbeds of discontent over the distribution of work, the decision-making process, the authority structure, and the appointment of credit. Researchers are attuned to a number of ethical issues like the ethics of covert observation and deception in experiments and the need for informed consent. Research in organizations can also be seen as something of a political minefield as is the case when the researcher is placed between opposite groups/parts of the industry under investigation.

There are certain recurring themes in organizational research: gaining entry to organizations and then getting on with people who work in them. While the field of organization studies has been heavily influenced by quantitative research, there is a growing recognition of the role of qualitative methods. Here we observe the associated difficulty of knowing how far generalizations from single cases can be stretched.

What we know or think we know about organizations is based on samples providing little external validity. Researchers sample organizations or sub-units of organizations in opportunistic ways. When they do achieve a modicum of generalizability, the populations from which samples are selected often are themselves defined arbitrarily… They rarely work with samples that are representative of even the restricted types of organizations they choose to study. This has often led them to develop bodies of theory that do not apply generally.

Studiesinto Olympic organizations, including thepresent one are not immune to the above challenges. Games impact studies are mostly carried out ex ante rather than ex post, are funded by government agencies and produced by global consultants (KPMG for the Sydney and London Games). Other pressures are felt by researchers considering mismanagement or corruption in global sports organizations like Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC). Such pressures may stem from the epistemic community as well as public culture when it becomes antipatriotic to report on negative aspects of the organization of the Olympic Games. Having been contractually bound to ensure the protection of the image of Olympism, Organising Committees for the Olympic Games (OCOGs) are particularly eager to avoid scandal or defamation at home as well as abroad and this has implications on the level of support they offer to researchers.

Furthermore, there is the problem of access to respondents from such organizations. Considering the fact that OCOGs are temporary organizations, it is possible to see that managers are quite busy before the games and immediately after the Olympic Games are over people leave the organization. Access to them is therefore often problematic and in addition to this the IOC has an embargo on recent corporate material. Even when access to OCOG interviewees prior to the Olympic Games is secured the issue of maintaining a positive image often surfaces as there are overwhelming pressures on staff not to compromise the company’s public image or risk raising issues prior to the IOC co-ordination commission visit.

Numerous studies have highlighted the complexity of doing research in another country. Issues and challenges may be interpreted differently there. Some issues are unique to that setting while some others become redundant. Hofstede (1980; 1984) studies on value differences highlight how these have implications on behaviour at work. Such values including power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, and masculinity versus femininity. The literature contains ample reminders of the challenges of doing research in foreign country, on culture’s consequences, on language and meaning (what Wittgenstein meant when he argued that: ‘Meaning is use. If you do not use a language on a regular basis then you cannot understand how it is used by the natives’ (Burrell, 1996)). Furthermore the challenge of gener-alizability is acentuated by the fact that as the Olympic Games are always held in a new country researchers need to be able to travel to the host city, maybe understand the language spoken there, and be able to add to their generic framework the particularities of the host city organizational environment. The Olympic Movement operates via a number of interconnected parts/units and to understand the movement, researchers and managers need to understand the component parts, the National Olympic Committees (NOCs), the International Federations (IFs), and the OCOGs. These straddle the spectrum of organizational activity. Some being limited companies, other charities, associations, or public companies. Having control over the Olympic trademark, and deriving its funds from the sale of exclusive rights, the IOC is eager to protect its monopoly business power. Current funding distribution arrangements create dependencies and conformity whilst ensuring the non-disturbance of the status quo. Research that exposes the profit-making beneficiaries has the potential to be received as damaging to the image of Olympism, of fair play and the joy found in effort. If such bodies are funding the research they may pressure exercised to clear material with them before it is made public and this may be felt as a form of censorship. Similar pressures can sometimes be felt on the broader epistemic community by political imperatives for growth of national identity and pride. Under such conditions it may be seen as antipatri-otic to critique Olympics-related efforts or processes.

There are also issues with respecting any anonymity request...