- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Design First

About this book

Well-grounded in the history and theory of Anglo-American urbanism, this illustrated textbook sets out objectives, policies and design principles for planning new communities and redeveloping existing urban neighborhoods. Drawing from their extensive experience, the authors explain how better plans (and consequently better places) can be created by applying the three-dimensional principles of urban design and physical place-making to planning problems.

Design First uses case studies from the authors' own professional projects to demonstrate how theory can be turned into effective practice, using concepts of traditional urban form to resolve contemporary planning and design issues in American communities.

The book is aimed at architects, planners, developers, planning commissioners, elected officials and citizens -- and, importantly, students of architecture and planning -- with the objective of reintegrating three-dimensional design firmly back into planning practice.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArquitecturaSubtopic

Arquitectura general

History

Paradigms lost and found dilemmas of the Anglo-American city

SYNOPSIS

In this first chapter, we examine four aspects of British and American city design, and in so doing we introduce several concepts that will be elaborated in subsequent chapters. First, we try to answer the questions that are often posed by practicing architects and planners about the value of history. ‘Why bother with history?’ they ask. ‘How are the events and ideas of a hundred years ago relevant to my work today?’

To help evaluate these questions, we discuss in the second section some of the ideologies and attitudes that have shaped our cities today – the founding assumptions of modernist architecture and planning as they were theorized and practiced in the middle decades of the twentieth century. The buildings created from these ideas spawned a legacy of unforeseen urban problems, and by the late 1960s and 1970s, the lack of success of modernist design generated anti-modernist reactions. These coalesced around reawakened interest in traditional forms of urbanism, such as the street and the square, which had been explicitly rejected by modernist theory and practice.

The third section examines aspects of these reactionary movements. We discuss some of the reasons for this reversal in attitudes, a theme that will be consistent throughout the book, and we look at some of the work that resulted from this more consciously historical perspective. In the final section of this opening chapter we confront one of the ironies of our period. At the very time of the revival and renewed ascendancy of traditional urbanism, revolutions in information technology and media have created a whole series of virtual worlds, communities and electronic places that threaten to render the public spaces of our towns and cities obsolete. Where does this leave the urban designer today? Is an urbanism based around a revived representation of traditional public space still relevant?

THE ROLE OF HISTORY

The community design professions have several choices today regarding the role of history. From one perspective, the architect or planner may choose to ignore history altogether in pursuit of a vision of an unfettered future. Or, thinking that the search for solutions to today’s complex urban design problems leaves no time or place for the ‘esoteric’ study of times past, a working professional may choose to pigeonhole history in the realm of academia.

Conversely, the professional who views his or her efforts as being part of a larger narrative, one that acknowledges the past as being relevant to the problems of contemporary practice, will likely address the role of history more positively. We hold this latter view regarding the importance of history to urban design and planning. Some of the urban concepts and values we use in our work stretch back (at the very least) to the beginning of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. We will argue in several places throughout the book that some urban concepts are ‘timeless,’ and can be found in western cultures in many periods of history, but for our purposes here, the late 1700s usefully define the beginning of what we might call the modern era in city design. It was then, just to the south of London, that the first modern suburbs started to develop.

As a pair of seasoned teachers and practitioners, we strongly believe we are more effective when we understand the sources and the histories of the urban design and planning concepts that we use. They did not arrive fully formed at our pencil tips and computer keyboards! Some continue recent trends, or reclaim discarded or outdated concepts; others are deliberate reactions against perceived mistakes of the past. Our ideas come with a history, and we are guided in our practice by the knowledge of how they were derived and how they have been used (and misused) by professionals in previous times and places.

But first we must be careful to define what constitutes our ‘history’. Historians and critics are often tempted to seek some overarching ‘grand narrative’ as a framework for their arguments (we are no different in this regard except that we are wary of the process and its results!) and for much of the twentieth century the history, theory and practice of modern architecture was presented as a unified, coherent story by writers such as Hitchcock and Johnson (1932), Pevsner (1936), Richards (1940), and Giedion (1941). In this tale of the ‘International Style,’ the heroes were Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilbersheimer, the artists and architects at the Bauhaus, and other pioneers of the modern movement. Under the intellectual leadership of this new avant-garde, a primary task of modern architects was to rid society of the environmental and social evils of the polluted industrial city, where workers lived miserable lives, crowded into unsanitary slums. In place of the old, corrupt Victorian city, modern architects envisioned a bright, new healthy environment, full of sun, fresh air, open space, greenery and bold new buildings free of the trappings of archaic historical styles. It was a terrific vision and a fulfilling professional mission.

The replacement of cities perceived as outdated and corrupt brought a bright new optimistic face to urban design. In war-ravaged Britain during the1950s, new blocks of flats rose heroically from the rubble. Some were sited, like those at Roehampton, in west London, in park-like settings deliberately reminiscent of Le Corbusier’s evocative drawings (see Figure 1.1 ).

All was not sweetness and light, of course. Implementation of the vision varied, and a tangible gap was revealed between the promise of the utopian vision and ‘real-life’ achievements on the ground. Within a couple of decades, the planning and design philosophies of the modernist agenda were being questioned by the public. Planners and architects first took a defensive position. They suggested that the bleak urban environments people were complaining about were simply the result of the great visions of the masters being interpreted by less talented pupils, but increasing popular discontent, particularly against programs of urban reconstruction in Britain and urban renewal in America, gradually made the modernist position untenable.

Figure 1.1 Alton West Estate, Roehampton, London, London County Council Architects’ Department, 1959. Bold versions of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation are set in the soft landscape of south London, creating an image of the modernist dream. Compare this image with Figure 1.4.

Within these unpopular urban settings, the architecture itself was disliked; the new buildings were decried as dull and boring boxes. While architects loved to use concrete, either poured-in-place or as precast panels, citing its ‘honesty’ or ‘integrity,’ the public perceived this material as unfriendly and hostile. The uniformity and abstraction of the International Style puzzled and dismayed a public used to a richer and more conventional architectural language of historical detail and imagery, even in the most modest of buildings. Over time, redeveloped urban areas bred a form of distaste and antagonism among residents who lived and worked there. In particular, the large tracts of semi-public space that were the norm in much urban redevelopment from the1950s through the early 1970s, gave rise to unforeseen and uncomfortable ambiguities about social behavior. This ‘free’ space for sunlight and greenery prescribed by modernist doctrine was achieved only through the destruction of old patterns of streets and urban blocks.

This open space was neither truly public nor private, and its consequent lack of spatial definition blurred boundaries and territories, raising issues of control and management, and ultimately of crime and personal security. Few people living in the large, modern housing redevelopments of slabs and towers favored by modernist theory felt safe or comfortable, or felt sufficient ownership of the open spaces around the new buildings to help take care of them. The list of failings in urban renewal and redevelopment schemes grew to such length and seriousness that ultimately it was impossible to treat these problems as teething troubles or poor applications of visionary ideas by less-talented designers. As urban historian John Gold has pointed out, a movement predicated on functionalism as a core belief could not withstand criticism about its dysfunctional consequences (Gold, 1997: pp. 4–5).

The conclusion was unavoidable: the ideas themselves were seriously flawed. Critic Charles Jencks famously ascribed the ‘death of modernism’ to the precise moment of 3.32 p.m. on July 15, 1972, when high-rise slab blocks in the notorious Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis, Missouri were professionally imploded by the city (Jencks, 1977: p. 9). Completed as recently as 1955, the buildings had been abandoned and vandalized by their erstwhile inhabitants to a degree that made them uninhabitable. Earlier, in 1968, a gas explosion and the consequent partial collapse of another high-rise block at Ronan Point in east London severely eroded the British public’s confidence in the safety of modernist highrise residential construction.

The tensions of urban life burst into the open during the British urban riots of the 1980s. Like their American precedents in the 1960s, the riots were the product of a clash between mainstream white culture and a black subculture built on deprivation and disadvantage, and were mainly focused on older urban areas of concentrated poverty, such as Toxteth in Liverpool, Moss Side in Manchester, Handsworth in Birmingham and Brixton in south London. The unrest and violence reached spectacular levels with the Broadwater Farm conflagration in Tottenham, north London, in 1985, and this was significantly different from the other urban areas of racial tension. Broadwater Farm was a ‘prizewinning urban renewal project of 1970, (which) had proved a case study of indefensible space; its medium-rise blocks, rising from a pedestrian deck above ground-level parking, provided a laboratory culture for vandalism and crime’ (Hall, 2002: p. 464).

There were several influential efforts to link this urban unrest directly to the failures of modern architecture and planning (e.g. Coleman, 1985). Although the social, racial and economic situation in 1980s Britain that bred the riots was far more complex than the cause-and-effect argument about the physical environment, the simplistic connection was a compelling one in the public mind. It was easier to blame the architecture than to deal with the deep-seated problems of social inequity and racial tension. With the hacking to death of a British policeman at Broadwater Farm and hundreds of riot police assailed by fire bombs, the tragic modernist blocks came to stand, like Pruitt-Igoe before them, for everything bad with modernist city planning and architecture.

Thus, what were truths for one generation quickly became doubts and finally anathema to the next. Faced with this ideological void, the younger generation of architects and planners sought to construct a new set of beliefs, and several premises of modernist urbanism were radically overhauled, and in many cases overturned. Many aspects of the search for new concepts focused around the recovery of more human-scaled spaces and an architectural vocabulary that connected with public taste. As we discuss more fully in Chapter 3, early postmodern architecture in the USA during the 1970s and 1980s incorporated ornamental classical details and elements of pop culture in an effort to bridge the communication gap between architects and the public. In the UK, this trend to glitzy ornamentation was also present, but a more substantive move was a return to an appreciation of vernacular building types and traditional urban settings. Just as the inclusion of ornament and kitsch into postmodern architecture was a conscious violation of modernist principles – a definitive rejection of the reductive, abstract aesthetics that had ruled professional taste for several decades – postmodern urbanism resurrected the traditional street, identified in modernist thinking as the villain and cause of urban squalor.

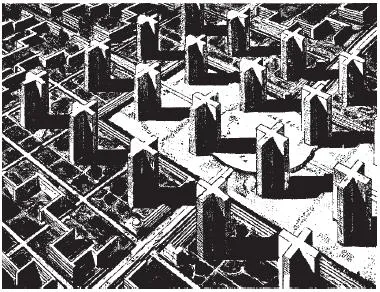

This renewed appreciation of traditional urban forms was presaged by Jane Jacobs in her landmark book The Death and Life of American Cities ( Jacobs,1962). Her description of the vitality and life on the streets of her New York neighborhood contrasted poignantly with the crime and grime of the urban wastelands produced by urban renewal, and while her criticism of modernist planning and architecture was largely dismissed by professionals during the 1960s, by the 1980s her book had become a standard text within this developing counter-narrative. Le Corbusier soon became the arch-villain of the new history, with his revolutionary and draconian proposals for ‘The City of Tomorrow’ identified as the source of everything bad about modernist urbanism (see Figure 1.2 ). Like countless other urban design professionals caught in the midst of this great revision of architectural and planning ideology over the last30 years, we (the authors) have often promoted our ideas of traditional urban form and space by contrasting them with a ‘conveniently adverse picture of modernism’ and its failings (Gold, p. 8).

Figure 1.2 Le Corbusier’s vision of The Contemporary City for Three Million Inhabitants, 1922. Tower blocks isolated in space and mid-rise slabs disassociated from the streets and set apart in landscape became the standard typologies for city building after World War II. (Drawing courtesy of the Le Corbusier Foundation )

In developing the new, improved grand narrative of postmodern city design during the 1970s and1980s, professionals turned to smaller scale opportunities instead of striving for new social and physical utopias. Architects started taking note of what was already in place and sought to enhance the urban fabric rather than erase it. The study of history and context became important again, and designers focused on ‘human-scaled’ development, with a particular emphasis on the creation of defined public spaces, often taking the form of streets and squares, as settings for a reinvigorated public life.

Our wholesale abandonment of modernist principles and their replacement by a radical return to premodern ideas poses something of a dilemma. Based on the belief that modernist architects and planners made serious errors about many aspects of city planning and design, we tell ourselves we won’t repeat the same mistakes, and consider our ideas much more appropriate to the task of city design. Here in America, our working concepts are based on traditional values of walkable urban places instead of the car-dominated asphalt deserts produced in the search for a drive-in utopia. We promote mixing uses once again, where for five decades functions were rigidly segregated, and we seek to involve the public directly in the making of plans instead of drawing them in the splendid isolation of city halls or corporate offices. We feel certain that these ideas are the right ones for the task of repairing the city and advancing the cause of a sustainable urban future.

But how can we be sure? After all, the modernist architects and planners we now criticize so harshly felt a similar degree of certainty in their mission and ideology. Have we merely replaced one professional paradigm with another that is also destined to fail, despite our good intentions? In the face of this conundrum, architects and planners must affirm their principles and their commitment to action; our cities and suburbs have a myriad of problems that demand urgent solutions. But, being neither fundamentalist nor unilateral, we must simultaneously reserve room for doubt, and be open to question. We have to allow the possibility that we are wrong, just as our predecessors were wrong before us! However, unlike our modernist forebears, we embrace the study of history and precedent in our work, and we heed George Santayana’s words: ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’ (Santayana, 1905: p. 284).

Accordingly, we pay particular attention to how modernist architecture and planning operated on the ground , the place where people were affected by it most directly. By observing the transformations of the nineteenth-century industrial city wrought by modernist pioneers and their disciples in Britain and America, we gain insight into the values and ideas that shape our post-industrial city today.

MODERNISM IN OPERATION

The story of city design is not straightforward. Even in our abbreviated history, themes weave and in and out of each other to form a complex tapestry. From our postmodern perspective we often mistake modernism for a monolithic construct, but this is far from the case. In architecture the early modernisms of Michel de Klerk, or Hans Scharoun and Hugo Haring, were far different from the unified vision that sprang into three-dimensional reality in 1927 at Stuttgart’s influential Weissenhoff Siedlung. This model housing settlement, master-p...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowlegment

- Credits

- Introduction: History, Theory and Contemporary Practice

- Part I History

- Part II Theory

- Part III Practice

- Part IV Preamble to Case Studies

- Afterword

- Appendix I The Charter of the Congress of the New Urbanism

- Appendix II Smart Growth Principles

- Appendix III Extracts from a typical Design-based Zoning Ordinance

- Appendix IV Extracts from General Development Guidelines

- Appendix V Extracts from Urban Design Guidelines

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Design First by David Walters,Linda Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arquitectura & Arquitectura general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.