- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this new edition, with a new preface and an updated bibliography, the author provides a comprehensive and well-documented survey of the evolution and growth of the remarkable military enterprise of the Roman army.

Lawrence Keppie overcomes the traditional dichotomy between the historical view of the Republic and the archaeological approach to the Empire by examining archaeological evidence from the earlier years.

The arguments of The Making of the Roman Army are clearly illustrated with specially prepared maps and diagrams and photographs of Republican monuments and coins.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Making of the Roman Army by Lawrence Keppie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Army of the Roman Republic

Rome naturally had an army from its earliest days as a village on the Tiber bank. At first it consisted of the king, his bodyguard and retainers, and members of clan-groups living in the city and its meagre territory. The army included both infantry and cavalry. Archaeological finds from Rome and the vicinity would suggest circular or oval shields, leather corslets with metal pectorals protecting the heart and chest, and conical bronze helmets. It must, however, be emphasised at the outset that we have very little solid evidence for the organisation of the early Roman army.

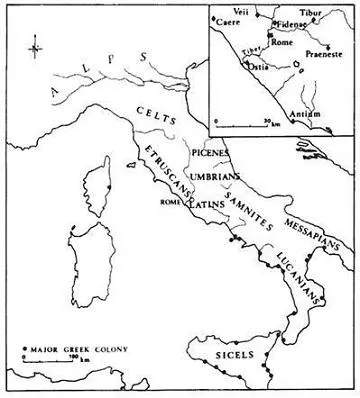

The wars between Rome and her neighbours were little more than scuffles between armed raiding bands of a few hundred men at most. It is salutary to recall that Fidenae (Fidene), against which the Romans were fighting in 499, lies now within the motorway circuit round modern Rome, and is all but swallowed up in its northern suburbs. Veii, the Etruscan city that was Rome’s chief rival for supremacy in the Tiber plain, is a mere 10 miles to the north-west (fig. 1).

In appearance Rome’s army can have differed little from those of the other small towns of Latium, the flat land south of the Tiber mouth. All were influenced in their equipment, and in military tactics, by their powerful northern neighbours, the Etruscans, whose loose confederation of Twelve. Cities was the dominant power-grouping in central Italy in the middle of the first millennium BC. Roman antiquarian authors have preserved a few details about the institutions of the early army, and it is perhaps just possible to establish some sequence of development. It was believed that the first military structure was based on the three ‘tribes’ of the regal period—the Ramnes, the Tities and the Luceres—all Etruscan names and so a product of the period of strong Etruscan influence. Each tribe provided 1000 men towards the army, under the command of a tribunus (lit. tribal officer). The subdivisions of each tribe supplied 100 men (a century) towards this total. The resulting force—some 3000 men in all—was known as the legio, the levy (or the ‘levying’). The nobility and their sons made up a small body of cavalry, about 300 men, drawn in equal proportion from the three tribes. These were the equites, the knights; all men who had sufficient means to equip themselves for service as cavalry belonged to the Ordo Equester, the mounted contingent (usually known now as the Equestrian Order).

1 Italy, c. 400 BC, showing major tribes and Greek colonies. Inset: Rome and vicinity

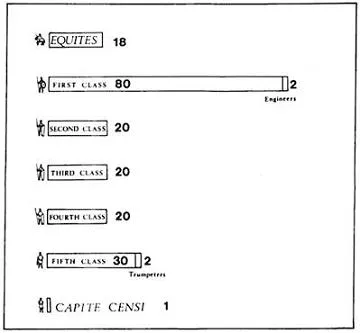

SERVIUS TULLIUS AND THE FIVE CLASSES

For the student of the early Roman army, it might seem that a fixed point exists in the reign of the sixth king of Rome, Servius Tullius, about 580–530. Servius is credited with establishing many of the early institutions of the Roman state. In particular he is said to have conducted the first census of the Roman people, and to have divided the population into ‘classes’, according to their wealth (see fig. 2). This Servian ‘constitution’ had a double purpose, political and military. In the first place, it organised the populace into centuries (hundreds) for voting purposes in the Assembly. The groupings were linked to the financial status of the individual, and his corresponding ability to provide his own arms and equipment for military service. Thus the resources of the State were harnessed to the needs of its defence. The equites, the richest section of the community, were formed into 18 centuries. Below them came the bulk of the population, who served as infantry, divided into five ‘classes’. Members of the ‘first class’ were to be armed with a bronze cuirass, spear, sword, shield and greaves to protect the legs; the ‘second class’, with much the same panoply minus the cuirass; the ‘third’, the same but lacking the greaves; the ‘fourth’ had spear and shield only, and the ‘fifth’ was armed only with slings or stones. In each class those men who were over 46 (the seniores) were assigned to defend the city against possible attack, while the remainder (the iuniores) formed the field army. Below the five classes was a group called the capite censi, i.e. men ‘registered by a head-count’, with no property to their name, who were thereby disqualified from military service.1

2 The ‘Servian Constitution’

The Servian reforms, it is clear, signalled the introduction at Rome of a Greek-style ‘hoplite’ army in which close-knit lines of heavily-armed infantry formed the fighting force. The Romans were later to claim that they had borrowed hoplite tactics from the Etruscans. This statement, which highlights the native Italic tradition, obscures the fact that the hoplites were an importation from Greece, where heavily-armed infantrymen had become the staple component of the battle-line by about 675. The hoplite (the word means a man armed with the hoplon, the circular shield that was the most distinctive element in his defensive equipment) was the standard fighting man at the time of the Persian and Peloponnesian Wars in the fifth century and of the armies of Athens and Sparta when Greek civilisation was at its height. The hoplites fought in close order, with shields overlapping, and spears jabbing forwards, in a phalanx (lit. a roller), which could be of any length, but usually eight (later 12 or 16) rows deep (pl. 1). Casualties in the front line were made good by the stepping forward of the second man in the same file, and so on. The phalanx was made up of companies of some 96 men, with a width of 12 men and a depth of eight.

However, it has been doubted whether a system of the complexity of the Servian Constitution could have been devised at Rome at such an early date. The first stage was more probably the establishment of a single classis, encompassing all those capable of providing the necessary equipment for themselves, so as to be able to take their place in the line of hoplites. All other citizens were designated as infra classem, i.e. their property was less than the prescribed level. In origin the word classis meant a call to arms—its more familiar meanings in Latin and English are a later development.2 The antiquarian writers report the strength of the new hoplite ‘legion’ as 4000, and the accompanying cavalry as 600. It should be remembered that throughout the Roman Republic the soldiers fighting for Rome were her own citizens for whom defence of the state was a duty, a responsibility and a privilege.

VEII AND THE GALLIC INVASION

In the last years of the sixth century, the ruling family of Tarquins was expelled from Rome, and a Republic established. A century of small-scale warfare against adjacent communities brought Rome primacy over Latium. The Etruscans meanwhile had declined in strength, faced by the hostility of the Greek colonies of southern Italy, their trading rivals, and by the onward surge of migrating Gallic (i.e. Celtic) tribes, who by the fifth century had penetrated the Alps, were pushing against Etruscan outposts in the Po valley, and were pressing southwards against the heartland of Etruria itself. In the long-term it can be seen that the Etruscans provided a buffer for the towns of central and southern Italy against the Gallic advance, which consumed much of their remaining strength. At the height of this crisis, in 406, Rome entered into a final round of conflict with her neighbour and arch-rival, Veii. Fighting continued in desultory fashion over a ten-year period, and was brought to a successful conclusion with the capture of Veii in 396 by the dictator M. Furius Camillus. The ten-year duration of the war prompted a patriotic comparison with the Trojan War. In order to prepare for the struggle against Veii the Roman army was apparently expanded from 4000 to 6000 men, probably by the creation of the ‘second’ and ‘third’ classes of the Servian system. Men of the second class had to appear for service with sword, shield, spear, greaves and helmet, but were not expected to provide a cuirass; men of the third class were to have spear, shield and helmet, but not the greaves. To balance the absence of protective armour, the new groups used the long Italic shield, the scutum, in place of the traditional circular shield of the hoplite. The scutum allowed better protection of the body and legs. A further sign of the changing conditions of service was the payment of a daily cash allowance to soldiers— the stipendium—which helped to meet the individual man’s living expenses while away from home for an increasingly lengthy period. The cavalry force of the legion was also enlarged, from six centuries to 18 centuries (1800 men). The members of the new centuries were provided with a mount at public expense (equites equo publico). Help from the public treasury was given towards the maintenance of the horse while on campaign.

The fall of Veii all but coincided with a further push southwards by the Gauls, who now penetrated into the Tiber valley, and in 390 threatened Rome itself. The new, enlarged army was swept aside on a stream called the Allia, north-east of Rome, and the town was captured and looted. Camillus was recalled to office, the floodtide of the Gallic advance soon ebbed to the far side of the Apennines, and Rome was saved.

ARMY REFORMS

The open-order fighting at which the Gauls excelled had shown up weaknesses in the Roman phalanx, and in the next half-century the army underwent substantial changes. The phalanx-legion ceased to manoeuvre and fight as a single compact body, but adopted a looser formation, by which distinct sub-sections became capable of limited independent action. These sub-units were given the name maniples (manipuli, ‘handfuls’).3 Moreover, there took place at the same time, or at least within the same half-century, a significant change in the equipment carried by many of the individual soldiers. The oval Italic scutum became the standard shield of the legionary—some were indeed using it already (above, p. 18).The circular hoplite shield was discarded. Furthermore, the majority of legionaries were now equipped with a throwing javelin in place of the thrusting spear. But, as we shall see, some men continued to be armed with the latter for two centuries or more. These changes in equipment are sometimes ascribed to Camillus himself, but they were probably introduced more gradually than the sources allow.

The new flexibility of battle-order and equipment, combined with a shift to offensive armament, were to be cardinal factors in the Romans’ eventual conquest of the Mediterranean world. The hoplites had worked in close order at short range, but the new legionaries were mostly equipped to engage with the javelin at long range, then to charge forward into already disorganised enemy ranks, before setting to with sword and shield. The Macedonians and Greeks, who maintained the traditional system, and later carried the phalanx to extremes of regimentation and automation, fossilised the very instrument of their former success, to their eventual downfall.

By 362 at the latest the army was split into two ‘legions’, and by 311 into four, which becomes the standard total. The word ‘legion’ now acquires its more familiar meaning, of a ‘division’ of troops. Command of the army rested with the consuls, the two supreme magistrates of the state, who held civil and military power for a single year and were replaced by their successors in office. Each consul usually commanded two of the legions. Sometimes, if a single legion was despatched to a trouble-spot, command could be held by a praetor. Each legion also had six Military Tribunes, likewise elected in the Assembly (see below, p. 39).

WAR AGAINST THE SAMNITES

During the fourth century Rome expanded her area of control southwards along the coastline towards the mouth of the Liris (Garigliano) river and inland across the mountains of southern Latium. This expansion soon brought her into conflict with the Samnites, whose confederation of tribes bestrode the highlands of the central Apennines. Conflict was almost inevitable in the wake of Roman expansion. The struggle lasted half a century, and ended with the complete subjugation of the Samnites. Rome’s army was not always successful, and the nadir of her fortunes was the entrapping in 321 of the entire army in the Caudine Forks.

In his account of the year 340, after the close of the First Samnite War, and as a preamble to a battle against the Latin allies, the historian Livy (who wrote much later, at the time of the emperor Augustus) offers a brief description of Roman military organisation, which was designed to help his readers follow the ensuing battle descriptions.4 He notes that the legions had formerly fought in hoplite style in a phalanx, but that later they had adopted manipular tactics. More recently (and he gives this as a separate development) the legion had been split into distinct battle lines (fig. 4). Behind a screen of light-armed (leve...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- PLATES AND LINE ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE (1998)

- INTRODUCTION

- 1: THE ARMY OF THE ROMAN REPUBLIC

- 2: MARIUS’ MULES

- 3: CAESAR’S CONQUEST OF GAUL

- 4: CIVIL WAR

- 5: THE EMERGENCE OF THE IMPERIAL LEGIONS

- 6: THE AGE OF AUGUSTUS

- 7: THE ARMY OF THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

- APPENDIX 1: THE CIVIL WAR LEGIONS

- APPENDIX 2: THE ORIGIN AND EARLY HISTORY OF THE IMPERIAL LEGIONS

- APPENDIX 3: NEW LEGIONS RAISED DURING THE EARLY EMPIRE

- APPENDIX 4: LEGIONS DESTROYED OR DISBANDED

- APPENDIX 5: GLOSSARY OF MILITARY AND TECHNICAL TERMS

- APPENDIX 6: LIST OF DATES

- APPENDIX 7: NOTES ON THE PLATES

- NOTES AND REFERENCES

- LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY