![]()

1

Craft training

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s there was great pressure for change in the way a craft skill is learned. Brickwork along with other construction industry trades has had its centuries-old tradition of Apprenticeship thoroughly examined.

There are three factors which have caused this re-examination of the Apprenticeship system, with a capital ‘A’:

(i) A desire for retraining people who may wish to leave one industry and enter another

(ii) A growing shortage of school leavers available and wanting to join construction trades throughout the 1980s, due to a falling birth rate 16 or so years earlier

(iii) A general feeling that just because you ‘missed the boat’ for vocational training when leaving school, you should not be denied the chance of learning a vocational occupation at any time in later life.

All this is far removed from the traditional arrangement of a school leaver joining a building company for a straightforward period of three or four years’ apprenticeship, with attendance at a local college of technology, as the only way into the construction industry.

Very many patterns of vocational training have been proposed and tried, and continue to be developed at the present time.

Current ET (Employment Training schemes), in operation at college and training centres for adult learners, are the Government’s response to change-factors (i) and (iii). Craft skills such as bricklaying, carpentry and plastering, which involve the use of tools and materials and require judgement of hand and eye, should not be confused with assembly processes. The knowledge and practice required to understand how to assemble metal partitions or false ceilings are far less demanding than the skills of setting, cutting, shaping and finishing the materials of the bricklayer, carpenter and plasterer.

Building and construction’s ‘lead-industry body’, responsible for developing change in training methods, has since 1964 been the CITB. This training board appreciates the difference between learning a craft skill in the one case, and that of becoming proficient at an assembly process in the second, by having separate development committees for the latter ‘specialist subcontractors’.

Many operatives in the construction industry enjoyed a traditional Apprenticeship with a caring employer, where a training officer monitored site experience and also progress with further education at a college.

Others not so fortunate rather ‘endured’ their Apprenticeship, which has given the expression ‘time serving’ a somewhat hollow ring.

The long standing two-part C&GLI (City and Guilds of London Institute) Examinations of Craft and Advanced Craft Certificates based upon syllabuses of practical work and related technology have been phased out.

Traditional barriers to achieving a qualification such as length and method of training, where and when skills are acquired and the age of the student/trainee, have now been removed.

Objective measurement of a student/trainee’s ability in the basic practical competences, step by step assessment of work modules, throughout the duration of a course of training aims to give a clearer indication of progress to trainer and trainee alike.

The construction industry is gradually moving towards a system where everybody working in it will require proof of their competence.

Schemes have been developed and are constantly being upgraded to keep in line with current trends: objective assessment of basic skills leading to NCVQ-approved (National Council for Vocational Qualifications), competence-based qualifications, which comprise a prescribed number of units of credit towards the award of an NVQ (National Vocational Qualification).

These, in association with C&GLI and CITB as the awarding body, are intended to fit in with the concepts of the EC (European Community), with whose policies of training for industry the UK is pledged to integrate.

Currently many competencies have to be achieved in the workplace to obtain an NVQ at levels 1, 2 and 3. This requires the student/trainee to be in employment and attend college part time. When students/trainees are in full time education they follow a similar programme but achieve competencies in the workshop under simulation, therefore obtaining CAs (Construction Awards at Foundation, Intermediate and Advanced levels). These can be upgraded to NVQs when the student/trainee has found employment in the construction industry and evidence can be achieved in the workplace.

Whatever form learning a craft skill takes, however, it remains an apprenticeship with a small ‘a’. Learning a craft remains a developmental process and must still provide sufficient time for repetition in practising the necessary manipulative skills of hand and eye on and off site, together with a sound knowledge of the technology of the trade, and the ability to draw if site plans are to be interpreted.

The student/trainee must realise that formal achievement of basic competences once only, in training, does not indicate total understanding.

Care must be taken by course organisers to see that sufficient job knowledge technology is retained in units of study leading to NVQs. Student/trainees need not only demonstrate how to carry out a craft operation but understand why it is constructed that way, if they are to gain the in-depth knowledge and ability to satisfy the demands of modern construction processes.

Despite all the changes in the manner and processes of learning a skill, the current uncertainties associated with training and the integration of C&GLI courses within the emerging structure of NVQs, brickwork remains an interesting, satisfying and challenging subject for a career.

![]()

2

Materials

It is a well-known saying in the industry that the craftsperson needs to understand the materials which they will use and lack of knowledge could result in materials being spoilt and work having to be taken down, both causing extra costs on the job.

Materials and methods are constantly being introduced into the industry and it is important that the users of these materials keep up to date with this ever-changing industry.

Bricks and their manufacture

The study of bricks, from raw materials to delivery of finished products, is an extensive one.

Being able to recognise a brick when it appears on site, know of its properties such as shape, size, weight, strength, porosity, colour etc. – and therefore know how and where to use it correctly – is all important basic knowledge.

Brick making is a very skilful business, with many individual variations in methods of manufacture between companies and their factories.

British Standards specify a brick as a walling unit designed to be laid in mortar and not more than 337.5 mm long, 225.0 mm wide and 112.5 mm high, as distinct from a building block which is explained as a unit having one or more of these dimensions larger than those quoted for bricks.

Bricks, which are one of the most durable materials, can be described as building units which are easily handled with one hand.

There are numerous uses for bricks but the main ones are as units laid in mortar to form walls and piers and the increasing use for brick paving.

Bricks were first made many thousands of years ago in hot climates, where a clay mixture was moulded and dried in the sun.

It was found that if the clay mixture was heated to a high temperature, the bricks were much stronger. The basic method of making bricks has not fundamentally changed.

Materials used for making bricks

Clay is the naturally occurring raw material used for producing most bricks. It consists mainly of silica and alumina.

Most clays also contain smaller amounts of limestone or chalk, iron oxide and magnesia. As natural deposits of clay in various parts of the country vary in their composition, a large variety of clay bricks are produced.

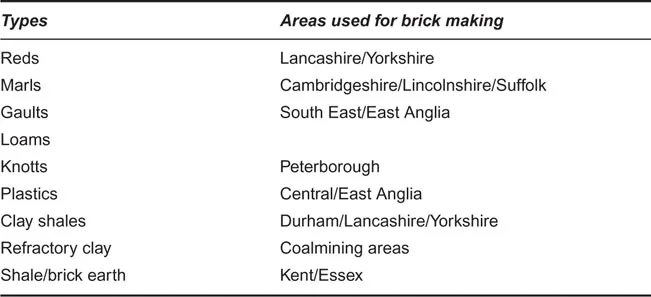

Suitable clays for brick making are reds, marls, gaults, loams, knotts and plastics, clay shales, refractory clays and brick earth.

They are found in many parts of the country, as shown in Table 2.1.

Note: Sometimes two or more types of clay are mixed together to produce bricks of varying colours and textures. Clays generally burn red, white or buff, according to the amount of metallic oxides they contain. Many different colours and shades have been created by the blending of clays.

Bricks are made by pressing a prepared clay sample into a mould, extracting the formed unit immediately and then heating it in order to sinter (partially vitrify) the clay.

Many types of brick may be produced, depending on the type of clay used, the moulding process and the firing process.

The stages of manufacture

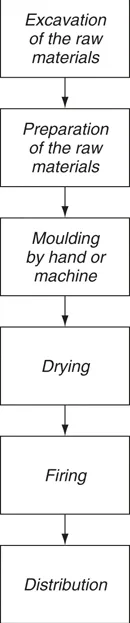

There are six stages in brick manufacture, though many of these stages are independent. Figure 2.1 indicates the six stages that will take place.

Figure 2.1 Stages in clay brick manufacture

1. Material excavation

The clay is excavated by machine from quarries close to the brickworks or brought into the brickworks from other quarries.

2. Clay preparation

After collecting, the clay is prepared by crushing and/or grinding and mixing until it is of a uniform consistency. Some clays have to be weathered so that soluble salts are washed out of them. Water may be added to increase plasticity and in some cases chemicals may be added for specific purposes – for example, barium carbonate which reacts with soluble salts producing an insoluble product.

3. Moulding

The moulding technique is designed to suit the moisture content of the clay, the following methods being described in order of increasing moisture content.

(a) Semi-dry process. This process, which is used for the manufacture of fletton bricks (ex London bricks – now part of Hanson brick) utilises a moisture content in the region of 10%. The ground and screened material has a granular consistency which is still evident in fractured surfaces of the fired brick. The material is pressed into the mould in up to four stages. The faces of the brick may, after pressing, be textured or sandfaced.

(b) Stiff-plastic process. This utilises clays which are tempered to a moisture content of about 15%. A stiff plastic consistency is obtained, the clay being extruded and then compacted into a mould under high pressure. Many engineering bricks are made this way, the clay for these containing a relatively large quantity of iron oxide which helps promote fusion during firing.

(c) The wirecut process. The clay is tempered to about 20% moisture content and must be processed to form a homogeneous material. This is extruded to a size which allows for drying and firing shrinkage, and units are cut to the correct thickness by tensioned wires. Perforated bricks are made this way, the perforations being formed during the extrusion process. Wirecut bricks are easily recognised by the perforations or the ‘drag marks’ caused by the...