- 472 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Techniques of Special Effects of Cinematography

About this book

First published in 1985. Exactly 20 years have passed since the first edition of this text appeared, in 1965. During this period, the author has gathered feedback from professional film-making circles. This fourth revision introduces new information in nearly all chapters. 130 new illustrations have been added, many of them illustrating feature films which are currently in release. The bibliography has also been enlarged considerably. The contributions of the visual-effects cinematographer have always been valued highly within the theatrical motion-picture industry. Because of their work, film producers have been able to endow their pictures with considerable 'production value' which the budget could not otherwise sustain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Techniques of Special Effects of Cinematography by Raymond Fielding in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Películas y vídeos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The techniques available

Nearly always, in the course of professional film production, the need arises for certain kinds of scenes which are too costly, too difficult, too time-consuming, too dangerous, or simply impossible to achieve with conventional photographic techniques.

These scenes may call for relatively simple effects, as when optical transitions such as fades, wipes and dissolves are used to link different sequences together. Or, they may be much more demanding, as when a city must be seen destroyed in an earthquake, when a non-existent, multi-million dollar building must be shown as part of a live-action scene, when actors on the sound stage must be shown performing in locales which are hundreds or thousands of miles distant, when pictorially uninteresting shots must be artistically ‘embellished’ through the addition of clouds, trees and architectural detail, or when fantastic events which contradict the physical laws of nature must be shown upon a screen in order to satisfy the demands of an imaginative script-writer.

Nature of special effects

The solution of these and many other problems of similar magnitude calls for the application of a set of non-routine photographic techniques, which, for the purposes of this text, we refer to as ‘special-effects cinematography’. Broadly speaking, special-effects work falls into two categories -photographic effects (sometimes termed ‘visual effects’, ‘optical effects’, or ‘process cinematography') and mechanical effects. In this book we treat only photographic effects.

Special-effects procedures are as infinitely varied in their application as the kinds of production problem which can arise, for each effects assignment is a new one, and is different in its peculiarities from every other one that has been done before.

It is this variety of problems and solutions which renders the field so interesting; it is the same variety which also makes the work of the special-effects cinematographer so complicated. There are few rules, if any, and mistakes are common. The tools of the art can range from simple, inexpensive devices which can be held in the hand, to extremely costly machines weighing a ton or more. The length of time spent on an effects shot can range from a few minutes to several weeks. In the end, only familiarity with the tools and techniques of the field will provide the right solution for a particular problem, and only a certain amount of experience will provide consistently professional results.

The techniques classified

The techniques which are available can be classified in a number of different ways. Basically, they can be described as being:

1. In-the-camera effects, in which all of the components of the final scene are photographed on the original camera negative.

2. Laboratory processes, in which duplication of the original negative through one or more generations is necessary before the final effect is produced.

3. Combinations of the two, in which some of the image components are photographed directly on to the final composite film, while others are produced through duplication.

Viewed in this fashion, the various techniques can be categorized in the following manner:

1. In-the-camera techniques

A. Basic effects.

1. Changes in object speed, position or direction.

2. Image distortions and degradations.

3. Optical transitions.

4. Superimpositions.

5. Day-for-night photography.

B. Image replacement.

1. Split-screen photography.

2. In-the-camera matte shots.

3. Glass-shots.

4. Mirror-shots.

2. Laboratory processes

A. Bi-pack printing.

B. Optical printing.

C. Traveling mattes.

D. Aerial-image printing.

3. Combination techniques

A. Background projection.

1. Rear projection.

2. Front projection.

This classification is necessarily oversimplified, for techniques in different categories are often used in combination or succession to produce a given visual effect. Thus, miniatures might be combined with live-action through bi-pack printing, or titles added through optical printing and traveling mattes to a composite of live-action and representational art-work which was originally produced by means of a mirror-shot. Also, many particular effects such as optical transitions, image distortions, image replacements, superimpositions and the like can be produced with substantially identical results through either in-the-camera or laboratory techniques. Since this is so, it remains to the cinematographer to decide which set of techniques is best suited to a particular assignment.

Chousing the right technique

Four criteria are central to the choice of technique: (1) image quality, (2) flexibility, (3) cost, and (4) the kind of production set-up available.

On the one hand, in-the-camera techniques provide the maximum image quality, inasmuch as they are photographed in finished form upon the original camera negative. Laboratory processes, on the other ‘hand, produce inherently poorer image quality, since they require the duplication of emulsions. Emulsion duplication, whether through contact or optical printing, reduces resolution, increases contrast and increases grain. In practice, this decrease in image quality may be so slight as to be negligible; still, the quality of image can never be as fine as that which is produced in the camera.

For a variety of reasons, but principally because of the economic impact of color television, nearly all motion pictures, in both 16 mm and 35 mm gauges are produced today in color. For all of this, the art of color cinematography remains an imprecise and uncertain one, vulnerable to those various factors which tend to degrade color images at different stages of production.

Workers will wish to experiment with a variety of both camera and duplication emulsions, in order to gain an intimate knowledge of each stock’s advantages and limitations. Duplication steps must be kept to an absolute minimum in color work, and the closest kind of liaison between cinematographer and processing laboratory must be maintained.

Theoretically, maximum image quality is always to be desired in cinematography. However, in special-effects work, this ideal must be balanced off against the flexibility of a technique. As the word is used here, flexibility refers to the extent to which a technique allows the cinematographer and director to control the timing relationships of action which appears in different components of the shot. It refers to the speed and convenience with which the shot can be executed, relative to the number of crew members who are tied up by the shot. Finally, it refers to the ability of the director to correct errors which occur during photography of the shot, and to experiment with different combinations of image components.

Flexibility

Generally speaking, in-the-camera techniques are rather inflexible. The timing of any live or mechanical action which occurs in the shot must be perfectly executed. The spacial relationships of the various image components must be precisely determined, as must any exposure, contrast or color-balance matches. Once captured on film, these variables cannot be altered at a later time. Since in-the-camera effects are made during on-stage production time, the entire cast and crew are tied up until their completion. Finally, if an error is made during the shot’s photography, there is no way to correct it, short of re-photographing the entire scene. The analogy which comes to mind here is that of the director who “cuts in the camera’. It can be done, but it had better be perfect!

By contrast, laboratory processes which involve the duplication of emulsions are almost infinitely flexible. Since all of the image manipulations or replacements are produced by re-printing one or more strips of film, the ultimate amount of control is provided over the timing of action and the balance of exposure and color values which appear in the various image components. Unlimited experiments can be made and, should an error occur, it is a simple matter to go back to the original production footage and start the printing steps all over again. Finally, much Jess ‘on-stage’ time is required to secure the required footage. Once this basic footage is shot, the remaining manipulations are conducted at leisure, far away from the sound-stage and by relatively few workers.

Generally speaking then, laboratory processes are much more versatile than in-the-camera techniques. There are some exceptions; when in-the-camera techniques such as glass- and mirror-shots are used for image-replacement purposes, they allow great precision and convenience in the determination of spacial relationships between image components. The effect of the final composite can be seen by the director’ and cinematographer at the time that the shot is made, merely by looking through the camera’s eyepiece, whereas when laboratory processes are employed, only an educated guess can be made as to how the separately photographed components will look when they are combined. This is an important consideration when working with directors or producers who do not understand what the special-effects cinematographer is capable of achieving, and who are loathe to entrust any part of the visualization or execution of a sequence to another individual. Finally, in-the-camera shots are returned from the laboratory the following day, together with the production ‘rushes’, at which time they can be immediately viewed and appraised. By comparison, an effects shot which is produced in the laboratory may be days or weeks in preparation.

Relative costs

The third and fourth criteria – those of cost and operational circumstances – are closely related; together, they usually constitute the determining factors in the use and selection of particular special-effects techniques.

On the face of it, in-the-camera techniques always appear less expensive than laboratory processes. The equipment whic is used is inexpensive and the shot can be made by the regular production crew. For example, insofar as equipment is concerned, a split-screen shot can be done in-the-camera at practically no cost. If the same shot is executed in the laboratory with an optical printer, it requires expensive apparatus plus the labor of the specialists who operate it.

The point that must be borne in mind, however, is that the cost of equipment is only one of a variety of costs that figure in a motion-picture budget; indeed, it is generally a relatively minor factor. Most of a production’s expenditure goes on labor – for the energy, the experience and the talents of the crew and the cast. A sizeable percentage of the budget also goes into sound-stage rental or over-head fees. In the business of film production, as perhaps more than in any other kind of business, time is money, and any kind of on-stage operation which ties up the cast, the crew and stage space for prolonged periods of time is inherently wasteful.

Many of the in-the-camera techniques are quite time-consuming. Although they require very little equipment, their successful execution takes so much on-stage time for set-up, rehearsal and shooting that the saving in equipment cost is more than offset by the delay they cause in the production schedule. For this reason, only the simplest of in-the-camera techniques, such as overcranking, undercranking, optical diffusion and day-for-night photography are ever employed on a major production.

For low-budget production, on the other hand, in-the-camera techniques may be found quite feasible. Working with longer shooting schedules, smaller crews and lower overhead costs, a small production organization can afford to employ glass-shots, mirror-shots, and certain types of in-the-camera superimpositions and matte shots. This is particularly practical when one or more members of the production team have an interest in special-effects cinematography, and the time to develop their individual skills.

Even in the case of low-budget production, however, many effects are more cheaply executed if achieved in the laboratory rather than on the sound-stage. Of course, laboratory processes require expensive equipment. In years past, low-budget 16 mm producers either had to conduct their special effects through in-the-camera techniques or eschew them altogether; they simply could not afford the costly investment which was necessary to set up their own special-effects facility.

Outside contractors

In recent years, however, with the spectacular growth of both 16 mm non-theatrical production, and the film-for-television business, scores of independent special-effects organizations have sprung up throughout the world to meet the needs of the impecunious producer who cannot afford to operate ?his own effects shop. Today, it is possible to contract virtually every kind of special-effects work to outsiders. Further, these service organizations will handle only so much of the special-effects assignment as the producer desires. In some cases, as with matte shots or optical printing, the producer may wish to execute much of the work with his own crew, and then send the footage out to the laboratory for completion. In other cases, as with background projection, he may wish to turn the entire operation over to the outside group.

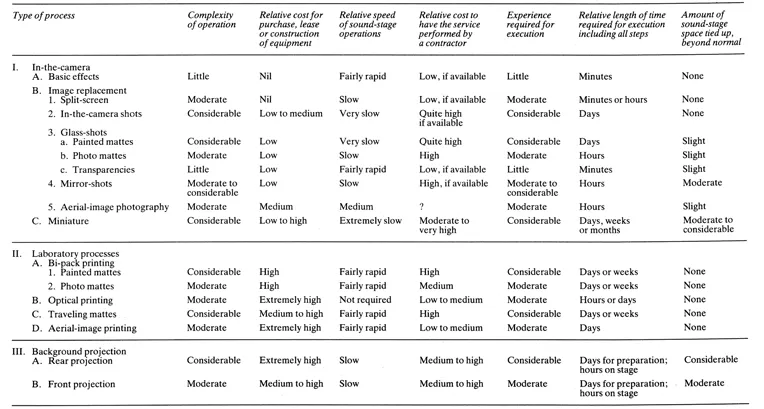

Special-effects techniques – their cost and operational characteristics

Facilities for 16 mm

Significantly, it is only within the last few years that special-effects processes have become practical for 16mm production, and that suitable equipment has been manufactured for the smaller gauge. Previously, the 16 mm producer who did not shoot his effects in-the-camera had to firs...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Preface to the fourth edition

- Acknowledgements

- 1. The techniques available

- 2. Camera equipment

- 3. Glass-shots

- 4. Mirror-shots

- 5. In-the-camera matte shots

- 6. Bi-pack contact matte printing

- 7. Optical printing

- 8. Traveling mattes

- 9. Aerial-image printing

- 10. Rear projection

- 11. Front projection

- 12. Miniatures

- 13. Electronic and computer systems

- Bibliography

- Index