![]()

Chapter 1

KTCK, “The Ticket,” Dallas-Fort Worth: “Radio by the Everyman, for the Everyman”

J. M. Dempsey

When KTCK, 1310 AM “The Ticket”—Dallas’s highest-rated, and oldest, sports-talk station—took the air in 1994, it earnestly endeavored to cover the local sports scene, with a little bit of postmodern, Seinfeldian attitude. It wasn’t long, however, before the attitude tail began to wag the sports dog. Today, The Ticket is all irony, all the time. Oh, yes, they also talk about sports, between hip takes on rock music, movies, and, most of all, sex. It’s all carefully calculated to satisfy the discerning tastes of the twenty-five- to fifty-four-year-old male.

In the highly fragmented world of major-market radio, a successful station need only capture a tiny slice of the overall audience. In Dallas-Fort Worth, the nation’s fifth largest radio market, urban (hip-hop, R&B) station KKDA-FM consistently scores the number-one position among listeners age twelve and up with about 6 percent of the audience. No station comes close to pleasing all listeners; indeed, to attempt to do so would be a disastrous mistake. So it is not surprising that The Ticket—owned by Susquehanna Radio Corporation—has its detractors:

I’m a 43-year-old male, and I listen to talk radio constantly. Except for Norm [Hitzges, late-morning Ticket host], The Ticket sucks! That’s just inane trash. It’s just boring prattle. So they have an opinion—so what? [The Ticket prides itself on “HSOs”—hot sports opinions.] They don’t have the clarity of thought to allow them to express the REASON for that opinion. And really, who cares what their opinion is? They’re all ass-holes!1

But The Ticket has successfully carved out a niche that allows it to claim the top spot in the ratings for adult males: “The Ticket succeeds like it does because it never takes sports or itself too seriously. It’s radio by the everyman for the everyman.”2

The Ticket’s faithful listeners, known as P-1s (“first-preference” listeners whose primary station is KTCK), strongly identify with the station and its personalities. Indeed, by identifying its listeners with the radio-ratings term “P-1” (otherwise unknown to the listeners), The Ticket uses a deliberate strategy of creating a virtual community of adult men joined together by their common interests, including The Ticket itself.

The sports-talk format enjoys an audience that is passionate about sports. The loyalty that listeners feel for their teams is often transferred to the local sports-talk stations, leading to higher-than-average time-spent-listening numbers and making the format attractive to advertisers.3 Nationally syndicated sports-talk host Jim Rome, asked to describe his audience, said: “I think they are rabid. I think they are passionate. I think they are loyal.”4

Social-identity theory5 explains how individuals attach part of their identity to the groups to which they belong. The related self-categorization theory6 further describes how people at times identify themselves as unique individuals and at other times as members of groups, and that each identity is equally meaningful. Each theory helps to explain the success of The Ticket.

FIGURE 1.1. KTCK logo.

In the context of radio, one study found that workers in the “textile belt” of the South during the period between 1929 and 1934 who lived in close proximity to radio stations had a greater sense of group identity and were more likely to strike. The study found that radio messages helped to shape the workers’ sense of collective experience.7

These theories have often been used to show the power of group identity in a sports context. For example, Platow and colleagues (1999) found that fans of a team are more likely to make charitable donations to solicitors who identify themselves as fans of the same team.8 Hirt and Zillman (1992) found that fans’ perceptions of their own competencies are affected by their teams’ fortunes, with some fans perceiving themselves as less capable following losses by their favorite teams.9 On the other hand, End et al.10 (2002), Lee11 (1985), and Cialdini et al.12 (1976) have studied the psychology of sports fans “basking in the reflected glory” of their favorite teams.

As with college and professional sports teams, The Ticket engenders strong identification among its listeners. It does this by conjuring a community of listeners joined not only by their interests, but also by attitudes and a common vernacular unique to the station.

* * *

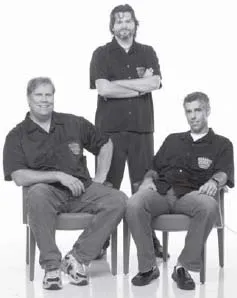

Each weekday morning, perched atop a sleek office tower in tony, uptown Dallas, a radio odd couple named Dunham and Miller (also known as “the Musers” for their oddly philosophical bent; see Figure 1.2) help thousands of sleepy P-1s start their days with a heavy dose of sarcasm-laced sports japery. To be fair, it is Craig “Junior” Miller who specializes in the sideways remark. Junior is the originator of the one of The Ticket’s most popular “bits” of fanciful irony: “The Girl on TV Who is So Good Looking We Need To Watch Out For Her Because She’s So Good Looking.” Junior is tall, lean, athletic, and decidedly single. His partner George (sometimes known as “Jub Jub”) Dunham, is tall, bearlike, agreeably ponderous in bearing and manner, and decidedly married. As the pair’s station bio explains: “George is married with three sons. Junior is single with three girlfriends.” Dunham and Miller are lifelong friends, and started working together in radio at the University of North Texas station, KNTU-FM, during the early 1980s.13

FIGURE 1.2. “The Musers,” KTCK, “The Ticket,” Dallas-Fort Worth: (left to right) George Dunham, Gordon Keith, and Craig Miller. Courtesy KTCK.

“There’s a lot of diversity in our talent,” KTCK general manager Dan Bennett said. “George and Craig are very different people. George is the settled-down, married guy with kids, and Craig isn’t [laughing at his understatement]. If all we did was hire a bunch of guys who were all alike, it wouldn’t be a very dynamic show.”14

Dunham said:

There are people who connect to me who don’t connect to Craig. And there are people who connect to Craig who don’t connect to me. Craig will say something and I’ll say, “Gee, I don’t know where Craig’s coming from with that. I don’t have much to add to this conversation.” But the single guy, who doesn’t have three kids like I do, does. The next day, if I talk about what a beating Little League Baseball can be, the nineteen-year-old may say, “Well, this is boring,” but the dad who’s slumped over the wheel because he was up until ten-thirty coaching baseball the night before can relate to that.

Sometimes it almost sounds contrived that he takes this stance and I take that stance, but it’s just that way. I don’t see things the way he sees them. It’s funny: We’re really unique in that most radio talk-show co-hosts have not been friends for twenty years. We used to see things exactly the same. We thought U2 was the spokesman for our generation, and we were going to change the world.

Dunham said creativity has always been an important part of his and Miller’s success going back to their college days. “No one would call,” George remembered of their college-radio talk show.

So we would “order” phone calls from the other guy. I’d host one week, and Craig would host the next. And before the other person would leave the station, we’d say, “All right, I want a concerned country guy asking about the North Texas defense, I want an older guy asking about the Cowboys, and I want a young guy asking about the Mavericks.” They would be left on carts [tapes], and we’d say, “All right, let’s go to the phones. Mike in Denton …” “Hey, how you doing, enjoy the show.” “Thanks.” “My question is …” It was ridiculous.15

* * *

The Ticket’s environs are very much what its listeners would imagine. The office is businesslike, yet decidedly casual, unquestionably male dominated. Dallas-area sports memorabilia is abundant—an autographed Michael Irvin Cowboys jersey hangs framed on one wall, a give-away Texas Rangers replica jersey is tossed haphazardly over the top of a cubicle, a high school football helmet sits on the floor by someone’s desk. A full-page Dallas Morning News “High Profile” article on Dunham and Miller looks out from a metal frame. Newspaper sports pages, sports magazines, and classic rock LPs are scattered everywhere. A personal photo of Alice Cooper is proudly displayed on someone’s desk.

Still, Bennett said the casual attitude conveyed on The Ticket is deceptive.

“I think they [listeners] would be surprised to know how much the guys prepare,” he said.

This is the hardest-working on-air staff I’ve ever been around. When people listen to The Ticket, they think it’s a bunch of guys shooting from the hip and it’s anything but. It’s really what we like to call sometimes “organized chaos.” But there’s a tremendous amount of organization that goes into it. Our guys get here hours and hours before their airshift, and put in tons of time before and after their airshift in preparation. There are a lot of people who think we just wing it, and that’s not true.

In the control room, a corporate message from parent company Susquehanna hangs above the window looking into the announcer’s booth where Dunham and Miller reside: “It begins and ends with product.” But the solemn admonition is overwhelmed by the flippant tone of a collection of bumper stickers that adorn the room: “Support National Thong Awareness Week” … “The problem is Jerry [Jones, Dallas Cowboys owner].” A display box for miniatures mounted on the wall is festooned with unwound audiotape. Among the throwaway sports novelties and buttons in the boxes, a small photo of a busty blonde with her teeth blacked out.

Board operator “Big Strong” Jeremy is the supreme master of a digital world. (In The Ticket’s endlessly ironic world, Jeremy is often addressed as “Big Strong.”) He sits surrounded by an array of five computer terminals. A virtual audio meter constantly pulses, green and yellow, while seconds resolutely tick away on a digital clock. By touching one of the multicolored boxes on a screen, he can instantly fire off a “drop,” in Ticket parlance a rapid-fire nonsequitur that can be lobbed into any discussion at any appropriate (or inappropriate) time. “I just know where they [the drops] are,” Jeremy said. “I can find ’em quickly if I have to.”16

George said The Ticket’s distinctive drops, like everything else on the Musers and the other shows, have evolved. Dunham reflected:

It just started with contrived movie clips, funny sounds, stuff out of the production library. I don’t know when it started that we would play something that, when you took it out of context and played it, it sounded really weird. That’s why you always hear “mark.” If someone says something that’s really strange, we started marking it and playing it back, basically to make that person look as bad as possible. If you do it right, it sounds like the guy is saying it live, and then everyone goes, “My gosh, why would he say that?” It’s part of the madness.

A favorite drop is the distinctive voice of The Ticket’s late-morning host Norm Hitzges. Norm, a veteran Dallas broadcaster in his fifties, is much older and more earnest than the other Ticket hosts, and faithfully sticks to sports as a topic for discussion, often building elaborate statistical arguments for his points. Hitzges’ high-pitched, giggling laugh is unmistakable, and turns up as a drop in programs around the clock on The Ticket.

Jeremy, a heavy-set but powerful-looking young man, has his own mike and inserts his own comments from time to time, as does producer Mike “Fernando” Fernandez, who sits at a table to Jeremy’s right, surrounded by this day’s local papers, current magazines, and sports media guides. Fernando will spend a good deal of the morning on the phone, making last-minute arrangements for show segments and fielding calls from listeners.

It is George who takes the lead in directing the show. The Ticket is enormously self-referential—the quirks and foibles of its hosts and announcers are eagerly pounced upon by other personalities, and endlessly ridiculed. As this morning’s proceedings are beginning, George ambles into the control room to consult with Jeremy. “George, what were you looking for from yesterday?” Jeremy asks. “When Rich [Phillips, “Ticker” sports-headline announcer] jumps on me about the cigarette thing,” George replies. Told the recording has been found, George responds,...