![]() Part I:

Part I:

Getting Ready![]()

Chapter 1

"How Do You Pick a Hotel?": A Brief Look at Consumer Behavior

To serve as an introduction to the subject of target marketing and segmentation, I would like to look at the subject of consumer choice from the consumer's viewpoint for a moment, as we will be spending most of the book looking at choice from the producer's viewpoint. The choice of organizing metaphor occurred during a recent family trip to Florida, coming soon after a similar trip to Oregon. In neither case did I make the hotel selection—but let us begin.

In 1995, my parents lived in Eugene, Oregon, a town of approximately 125,000, located in central Oregon. The town has two industries: lumber products and the University of Oregon. Eugene sports several hotels and motels: at the time, a downtown Hilton, a Holiday Inn, and a Red Lion led the list of "big names." Near the University there is a plethora of cheap motels of no distinction, plus a few where visiting faculty and parents feel comfortable staying. The leading motel in town is the Valley River Inn, a large facility away from the University on the Willamette River near Valley River Center shopping mall. Containing well over 200 rooms, it boasts meeting facilities and a good restaurant. My family had stayed there before while visiting my parents and we were quite satisfied with it.

When it came time to plan our stay for the fall 1995 trip to Eugene, my parents suggested the Holiday Inn; it was closer to their house, the kids would stay and eat free, there was a playground at the motel, and the room rate was considerably less. I told my kids that Grandma wanted them to stay at the Holiday Inn instead of the Valley River; they were vocally disappointed. I told them that Grandma and Grandpa were paying for the hotel and if they wanted to dispute their grandparents' choice, they had better do it because I was going to stay out of the fight. Needless to say, grandparents being what they are, we stayed at the Valley River Inn.

Why? There is nothing wrong with Holiday Inns. My kids don't know that, having never stayed in one before; although my daughter has stayed in one (but not my son), it was so long ago that she does not remember. But they had stayed in the Valley River Inn and wanted to go back there, preferably to the same room.

Why the loyalty? For one thing, there is the inertia endemic to children—the comfort of doing something again versus the discomfort of doing something for the first time. But there is more. The Valley River Inn staff work hard to make their guests feel welcomed, whether they were five and nine, or fifty-nine. Further, there were touches that would stick in any customer's mind. The Valley River's turndown service features a large Red Delicious apple on the pillow rather than a mint—this is Oregon, after all. They rent bicycles to their guests to ride along the bike path that runs for miles along the river right outside the hotel. Wild blackberry bushes abound right outside the hotel grounds, free for the picking and eating with breakfast. All in all, I cannot quibble with my kids' choice of hotels.

Then, in November, we took another trip, this time to Daytona Beach where my in-laws have a second home. My father-in-law made the reservations for us; his first choice was the Days Inn (because they had stayed there while looking for their mobile home and were familiar with it), but the inn did not have any rooms, so we stayed at the Ramada Inn Surfside. It was a satisfactory hotel, with a full kitchen so that we could eat breakfast in the room, and the usual beach hotel amenities—pool, beach, pool towels, etc. Nothing great, but more than adequate.

With a population in the area of a quarter of a million, there are an astounding number of hotels and motels on the beach. The Daytona Beach (and area) Yellow Pages lists thirteen pages of hotels and twenty-seven pages of motels. Even allowing for some duplications between the categories, this is an awful lot of guest rooms. By contrast, the Cleveland Yellow Pages directory has four pages for an area not only seven times larger in population, but larger in geographical extent. But Daytona, of course, is a snowbird destination and needs hundreds of hotels to house them.

And what a variety of properties! Everything from an Adam's Mark hotel across from the new convention center to an eight-room concrete-block building right out of the 1950's matchbook cover. "You can own your own business." In the approximate mile between our hotel and my in-laws' mobile home, there was a large Comfort Inn, a Holiday Inn (which my kids booed every time we passed, in memory of my parents' attempt to deny them staying at the Valley River Inn), a Days Inn, a Howard Johnson's, fifteen smaller motels, at least two "beach club" time-shares, two large condominiums (with rooms for rent, certainly during the out-of-season period) with another huge condo building going up. On the ocean side of the street, there is nothing but rooms for rent. Everything else—bathing suit and souvenir shops, miniature golf, ABC stores, restaurants, shopping centers—is on the other side of Route A1A, as are a few motels.

How does one make a decision about where to stay? When I asked my father-in-law why he had picked the Ramada when the Days Inn was full, he said: "Easy. It was the only name we could remember in Cleveland when we made the reservation." This, of course, is a clear statement of the need for advertising and the biggest signs allowable so that people will remember your property. But how is someone supposed to decide from a Yellow Pages entry? Do you stay at Holiday Inn (no surprises)? Not in my family anymore. Treasure Island Inn? Turtle Inn (a clear favorite with my kids because of the name and the sign outside)? Anchorage Family Motel (with its unmistakable Alaskan overtones)? Buccaneer Motel? Caravel Motel? Lazy Hours Motel? New Frontier Motel (with its two heated pools)? Peter Pan Motel (on the "wrong" side of the A1A)? Robin Hood Motel? The Talisman? Or the Whale Watch Motel? How does one choose?

Obviously, the Yellow Pages are not the only source for information that a typical traveler will use. There are the AAA Guides, and others, which give facts and figures —and sometimes great descriptions. After one has visited an area once, other possible hotels or motels seem to jump out. When we stayed in Newport, Oregon, we chose the Whaler Inn from the AAA Guide based on the description and the name, and were not disappointed. When we drove around the area, we noticed a bed-and-breakfast guest house that would be nice if we returned after our kids were old enough to stay at a bed-and-breakfast. But how does a customer choose?

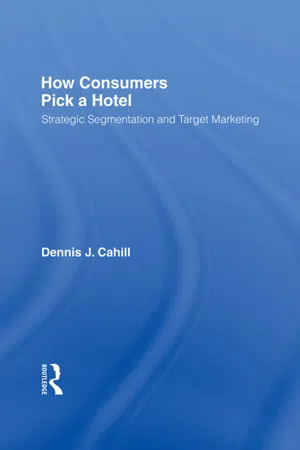

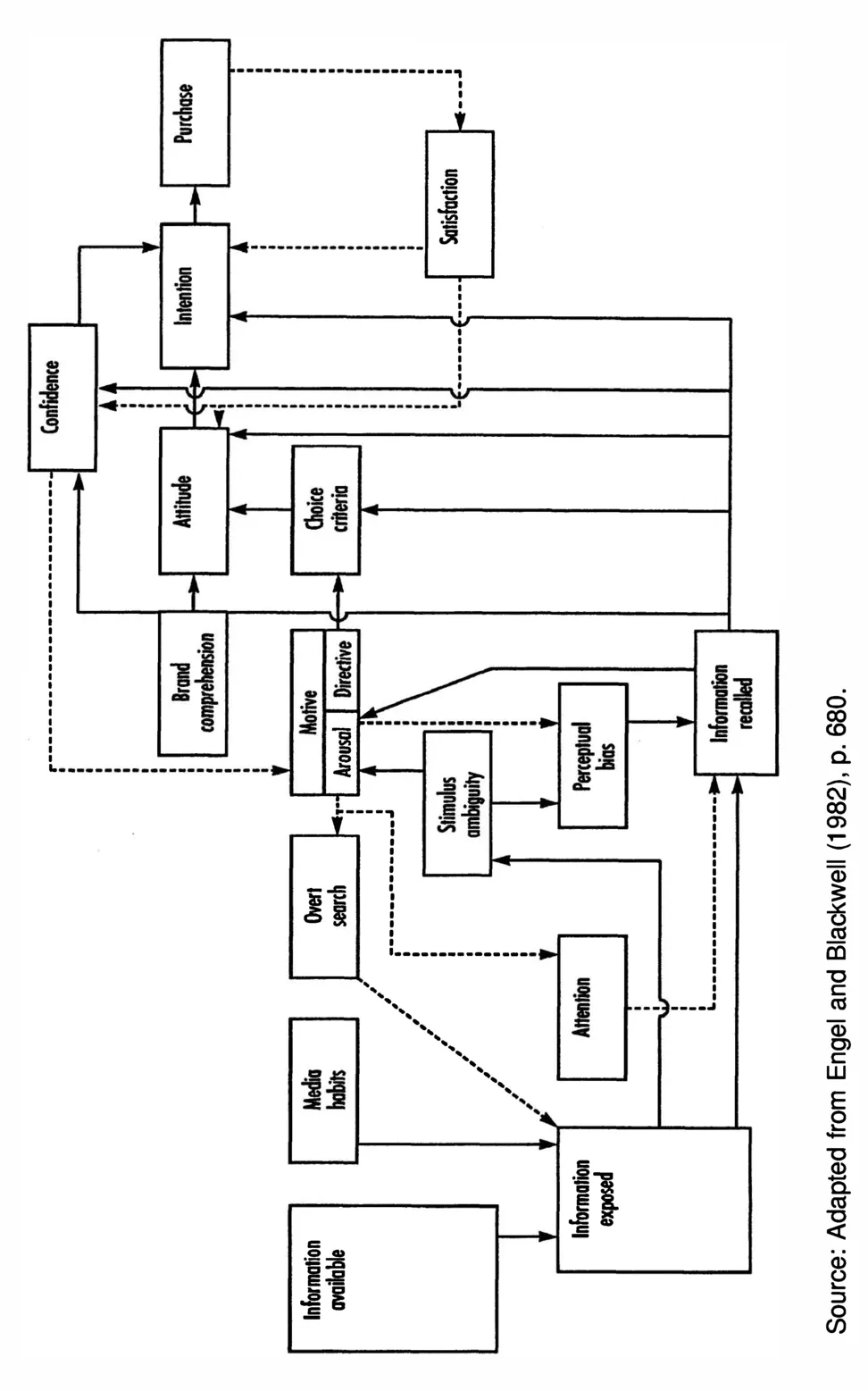

A large amount of research and writing has gone into the field of consumer psychology and behavior over the years. Much of this research has led to the development of various models of consumer behavior, both graphic and mathematical. Two of the earliest and most prominent models, at least one of which will be familiar to all who have had a course in consumer behavior in the last twenty years or who read the chapter on consumer behavior (or, if they are old enough, the chapter on "buyer behavior") in their general marketing textbook are: the Howard-Sheth model (see Figure 1.1) and the Engel-Kollat-Blackwell (EKB) model (see Figure 1.2). Both are elaborated on in Engel and Blackwell (1982) and other textbooks. These models attempt to describe and explain the process by which consumers decide to buy a product or service. As they are presented, they seem terribly overelaborate; often it seems that consumers conduct the entire process in an unconscious state.

Although I would not wish to diminish the differences between the two models, there are remarkable similarities. Both start with the recognition by the consumer that there is a dichotomy between a desired state and reality, proceed through a process of searching for a way to end the dichotomy, weighing alternatives, making a choice, making the actual purchase (thus betraying the "buyer-behavior" orientation of the field in the 1960s and 1970s), and dealing with the outcome. Although these models probably do not describe the process by which we buy chewing gum or other trivial items, they probably do fit, at least in descriptive terms, the way we buy houses and cars. (See Cahill, 1994a for an extension to this model for houses.)

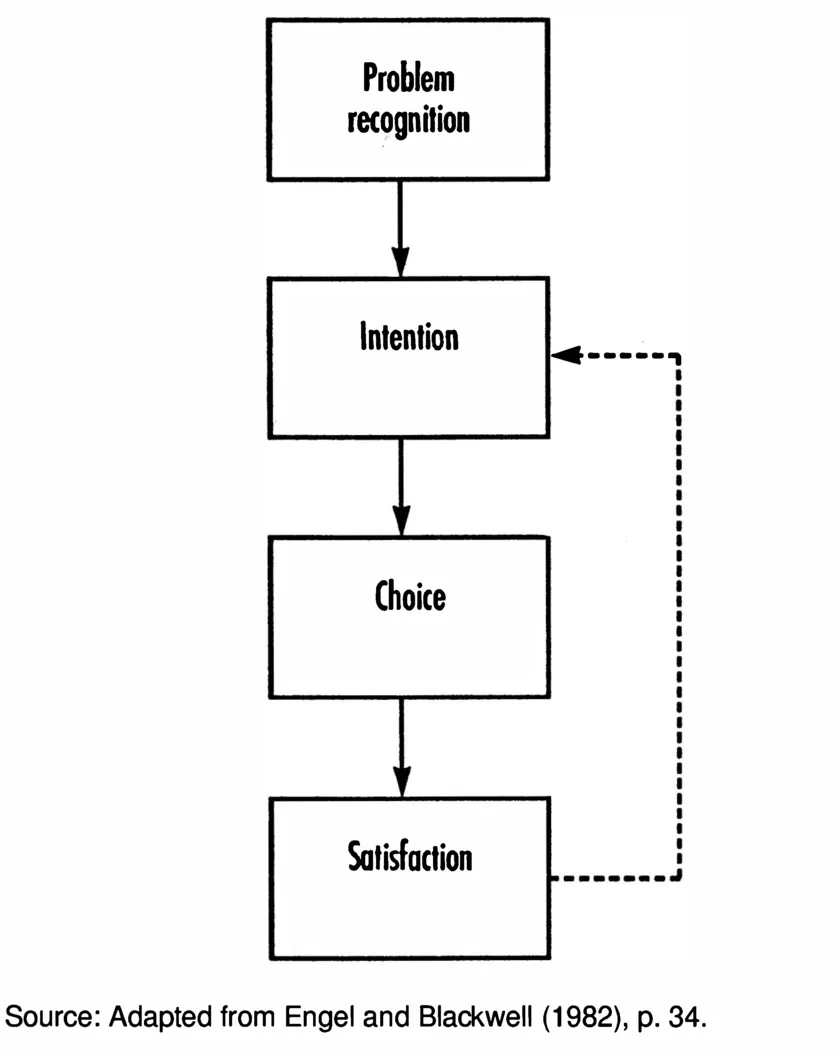

How do the models deal with the choice of a hotel? Let's follow through the steps in the unelaborated EKB model (Figure 1.3) and see. We start with "Problem Recognition." My family was going to visit grandparents, neither of whom had enough room for the four of us in their house; therefore, we needed a room to rent. The next step is "Search." In neither case above was "Search" particularly elaborate; there were not that many alternatives in Eugene to choose from, and in Daytona Beach, although there are hundreds of alternatives, my in-laws could not remember any of them. "Alternative

FIGURE 1.1. Howard-Sheth Consumer-Behavior Model

FIGURE 1.2. Engel and Blackwell Consumer-Behavior Model

evaluation" was simplicity itself in Daytona Beach: Days Inn had no rooms, Ramada Inn did, and that was it. In Eugene, however, none of the alternatives truly mattered because of a behavioral idiosyncrasy in the buying unit, in this case, the grandparents. "Choice" is almost a misnomer in both cases because there were no choices to be made. "Outcome" was favorable in both cases. Is the model descriptive of the process? It appears to be—at least in these cases.

However, in the almost-thirty years since the EKB model was developed, there has been a shift in the field of consumer behavior studies. As mentioned above, the field used to be focused on "buyer behavior," but that has changed; the same tools have been used on actions where no money changes hands, such as the viewing of television shows, with gratifying results. Holt has developed a

FIGURE 1.3. Simplified Engel and Blackwell Consumer-Behavior Model

typology of how consumers consume and what types of actions are subsumed in the term "consume" (1995). Although most consumer studies have traditionally been psychology-based, there have been some attempts to look at the social and societal components (Nicosia and Mayer, 1976; Hirschman, 1985; Rook, 1985).

In perhaps the most sweeping and drastic argument about consumer behavior, Morris Holbrook issued a call to change the entire field of consumer research away from buying and back to consuming, saying:

I ... propose an expansion of consumer research to reflect a fuller treatment of (1) consuming (versus buying), (2) experiencing (versus deciding), (3) using products (versus choosing brands), (4) intangible services and ideas (versus tangible goods), (5) more (versus fewer) durable products, (6) expenditures of time, effort, and ability (versus money), (7) emotional components (versus narrowly defined affect), (8) consumer misbehavior (versus behavior), (9) mutually interdependent wholes (versus their parts), and (10) concern with consumption for its own sake (versus managerial relevance).... (1987:173)

In the years since Holbrook's call, much of this has happened; some had happened before it. The study of consumers and consumption is now close to being truly multidisciplinary; we are examining aspects of the process that were never thought important before. In fact, Holbrook's Consumer Research (1995) captures the history of change in detail. (See also Cahill, 1996b and 1996c for a review of the field, and Cahill, 1994b for a brief discussion of some of the problems such a stance creates.)

Nevertheless, there is one part of Holbrook's call that is disturbing: there runs through the entire book in which the Holbrook chapter appears a sense that consumer research should be elevated to the status of "consumer science" and divorced from any taint of usefulness; much of this plaint seems to derive from the fact that most of the consumer researchers are housed in business schools and thus lack academic respectability—certainly in the eyes of many of their colleagues in arts and sciences. As a former graduate student in American history, I can understand, empathize, and sympathize with those who desire to do research that interests them, regardless of whether it leads to anything "useful," as Holbrook so adamantly hopes for. However, there is a question of the worth of much of what passes for "research" in the consumer field; it frequently seems to have been designed to avoid any taint of usefulness. And worse, all too often when one reads the published results of much of it, one has a sense of "so what?" I can cite dozens of examples, but will refrain. Rather, I will cite some conditions which should serve as red flags to the problem when one reads such a research paper, although the presence of one of these condi tions should not be read as disabling—nor even two or three, necessarily.

First, the paper is based on the author's dissertation. Second, a sample of students is utilized. If the research is about computer programs, CDs, jeans, T-shirts, or other items which college students buy and use, such a sample is no problem However, if the study is about cars, houses, cooking, or something similar—beware. Third, a long list of references having to do with deconstructionism, postmodernism, or some other "in" topic is a sure indication that the author is off doing research that will bear no relationship to anything in the "real world." Fourth, the authors start out with the statement that their qualitative methodology needs to be considered "science" and cite Thomas Kuhn's 1970 seminal work; as I have complained elsewhere, this is a waste of talent (Cahill, 1993). Again, I am not stating that all research needs to be applications-oriented; my point is that too much of what is being done in consumer research is simply incestuous, academic mental masturbation, designed to build a curriculum vita for the author so that when it is time to build a tenure file, the requisite number of publications in the "right" journals will be there. It certainly does not create answers to questions that anyone outside of academe has ever asked. Rather, if one wants answers to the questions normally asked by practitioners—what do people want? how much do they want? what will they pay?—one needs to go to different sources. The Wall Street Journal published two studies in 1990 which answered these questions in no uncertain terms (1990a, 1990b), but they certainly need updating by now

It is my contention here, and that contention will be reinforced throughout the remainder of the book, that the consumer's choice is led by the producing firm which has targeted a particular kind of customer that it wants. It does this through a variety of methods: from the name it chooses and the logo it designs, to the methods by which it communicates with its customers. And, of course, by the content of those communications. Ramada has recently advertised to the travel industry that they are changing, stating, "We are simplifying our choice of properties—making it easier for your clients to pinpoint the type of Ramada they'll need on any given trip." Pollay and Mittal (1993) have even used segmentation by personal utility and socioeconomic factors to identify attitudinal segments toward advertising in general in the U.S. population.

A successful firm will be conscious of the targeting and communications, integrating these into a coherent, consistent message which is conveyed to the customers and prospects. An unsuccessful or less successful firm will not have a tight grasp on the program, and its messages will be scrambled. Keeping ...