- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book addresses the social and organisational dynamics which underlie recent technological and work developments within organisations. often referred to as 'virtual working'. It seeks to go beyond a mere description of this new work phenomenon in order to provide more rigorous ways of analysing and understanding the issues raised. In addition to providing accounts of developments such as web-based enterprises and virtual teams, each contributor focuses on the empolyment of information technology to transcend the boundaries between and within organisations, and the consequences this has for social and organisationaL relations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Virtual Working by Paul Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

From new designs to new dynamics

Paul J. Jackson

As we stride across the threshold of the new millennium, many of us will find just cause to contemplate the world that lies ahead. A new millennium offers us all the chance to wonder and even dream how things may be different in the future – what changes may lie in store for the way we live and work; what new technologies may shape our lives. If we look just into our recent past, there is evidence that the scope and speed of change can be dramatic. Social and economic consequences of globalisation, for instance, have shown us how an increasingly interdependent world produces common problems and concerns that demand new forms of international management and new types of organisations. Developments, not least with the Internet, demonstrate how new technologies can spring, seemingly from nowhere, with pervasive consequences.

The introduction of new information technologies (IT), computer software and multi-media interfaces – particularly the World Wide Web – offer the possibilities of finding new ways of working and learning, new products and services, and even entire new industries. But this also comes at a time of heightened competition and of pressure on firms to be adaptive and innovative. The new possibilities are therefore tempered by uncertainty and anxiety. It is in this context that discussions of and developments in ‘virtual working’ are taking place.

The rise of virtual working

In one sense, virtual working is bound up with attempts to find ever more flexible and adaptive business structures. It addresses the need to break with old, bureaucratic ways of working, and to allow for rapid innovation and product development (Davidow and Malone 1992; Birchall and Lyons 1995; Hedberg et al. 1997). Business success, as Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) have pointed out, increasingly relies not only on improving efficiency, but in embodying ideas and knowledge in products and services that are rapidly developed and deployed in the marketplace. But bringing new ideas and knowledge together may call for a change to traditional business practice, particularly where many different expert groups are involved (McLoughlin and Jackson, Chapter 11 this volume). Specifically, collaboration across functional boundaries, and even between organisations, may be required (Hastings 1993). In both cases, a need to transcend spatial barriers may also be pertinent, particularly where groups of experts are located in distant offices and countries (for example, see Lipnack and Stamps 1997 and Nandhakumar, Chapter 4 this volume). In this instance, then, the virtual working debate draws attention to the contrasts with old, ‘Fordist’ style organisations, which were generally vertically integrated, with all activities and skills housed within a single legal entity (see, for example, McLoughlin and Clark 1994; McGrath and Houlihan 1998; Harris 1998).

The breaking down of spatial barriers represents another key dimension of the virtual working debate. This has been given impetus in recent years by new forms of IT, particularly intranets and extranets, video-conferencing and mobile communications. Bridging distance with IT is a subject most closely associated with the idea of ‘telework’ (see Jackson and van der Wielen 1998). Of course for many people, telework has traditionally had a more restrictive meaning than that encompassed by virtual working, referring largely to flexible work arrangements. Here, individuals use IT to work (or telecommute) remotely from employers, at specially designed ‘telecentres’ or ‘telecottages’, at home or on the move (see also Nilles 1998).

As Jackson and van der Wielen point out, though, while telecommuting may provide a number of important benefits for both workers and their employers, the flexibility offered by the new technology provides for more than just doing the same or similar work tasks at a distance. As noted above, the opportunity to blend expertise across space, or the linking of enterprises to form collaborative networks, points to more powerful uses of the technology. This more strategic approach to virtual working (and the technologies that facilitate it) will be needed if contemporary business imperatives are to be addressed.

The basic premise of this book is that while these work structures and processes (inter-firm collaboration, flexible working, team working, knowledge management and organisational learning) are often treated in isolation, given the growing importance of IT and spatial flexibility to them, there are merits in examining their areas of connection. This will allow us to draw out points of contrast, as well as to see where lessons can be generalised. The new organisations and (virtual) ways of working that characterise the new millennium demand a systemic elucidating of these issues. Three reasons underpin this:

- The demand for more flexibility by individuals, combined with improvements in technological capabilities and cost-effectiveness, will make working arrangements, such as teleworking, increasingly viable and attractive.

- The need for organisations to improve innovation and learning will demand new knowledge management systems, making use of IT support, that help members to acquire, accumulate, exchange and exploit organisational knowledge.

- Because access to and transfer of knowledge and expertise will increasingly take place across boundaries (both organisational and spatial), internal networks and dispersed project groups, as well as inter-firm collaborations, will become more and more common.

From designs to dynamics

A whole new lexicon has arisen that seeks to capture the new ways of working described in this book, including ‘Web enterprises’, ‘virtual organisations’, ‘virtual teams’, ‘teleworking’ and so on. In many accounts of the new work configurations, attention is generally given over to describing the new forms or structures involved and what role the new technologies have played. Many of the experiences, achievements and benefits derived by the early adopters have been documented (Cronin 1995 and 1996; McEachern and O’Keefe 1998). These works are clearly important for illustrating new business models and working practices. However, this book seeks to move the debate a stage further by wrestling with the challenges involved in migrating towards and managing these new ways of working. In doing this, the book addresses two sets of concerns. The first recognises that in introducing forms of virtual working – from networking, to virtual teams and teleworking – particular problems and issues are faced by those charged with managing the change. The second points to the fact that such developments also bring with them a need for new skills, procedures, and even values and attitudes, on the part of workers, team members and managers. These two sets of concerns are what we refer to as ‘social and organisational dynamics’. They are, it can be argued, the key challenges in virtual working over and above those of designing new work configurations or implementing the technologies that support them.

The problem here is that in introducing new ways of working, or in making sense of new work phenomena, there is danger of repeating the sort of mistakes made, for instance, in the world of information systems design. As Hirschheim (1985) pointed out, writers on and designers of information systems often addressed themselves to the ‘manifest’ and ‘overt’ aspects of organisations (technologies, information flows, work tasks, and formal structures and relationships), to the neglect of the ‘cultural’ and ‘social’ aspects. As Harris et al. (Chapter 3) and McLoughlin and Jackson (Chapter 11) note, the introduction of new technologies and corporate change strategies are still often looked upon as relatively non-problematical ‘technical matters’.

One reason for this may be the complexity of the ‘technical’ knowledge involved (Attewell 1996). Few people have the business, technical and human resource expertise to grapple easily with such matters. It is not surprising, perhaps, that where new work concepts are produced (for example, by IT vendors or writers and consultants), and ‘off the peg’ software suites developed, they may stand in lieu of a thorough organisational assessment as to the strategic opportunities and implications of technology-supported change. There is also a danger here in the way successful cases of work innovation are documented and discussed, giving the impression that other firms could straightforwardly hope to emulate them. This may again downplay the complexity involved in managing the new work structures, as well as the know-how needed to appropriate benefits from the technologies (Stymne et al. 1996). Subtle differences – from market conditions and organisational cultures, to political agendas and expertise levels – makes the transplantation of any technique or technology from one case to another fraught with difficulties.

New organisational thinking

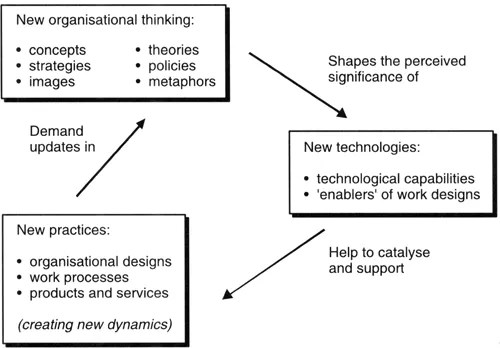

One problem, of course, is that the rate of current technological and business change allows little time to get to grips with the intricacies of new devices and software, or for considered reflection on the sort of systems and competencies needed to manage the new work configurations based on them. The pace of change, and the pressure to innovate, thus presents two main challenges. The first is to embrace the ‘potential’ of new technologies in order to realise competitive benefits through new work structures and processes, as well as products and services. We can characterise this challenge as one of ‘new practices’. The second and related set of challenges address ‘organisational thinking’. This includes, for instance, the theories and concepts we use to describe and understand new practices (see also Checkland and Holwell 1998). It also encompasses the strategies and assumptions that guide decision making about them. Where new practices present particularly novel dynamics (such as ‘remote management’ in teleworking, or knowledge management in Web enterprises) the need for new organisational thinking (theories, strategies, attitudes) becomes sharper. This may also mean questioning fundamental assumptions about work and organisation – things that are often captured in the language and implicit metaphors we use when talking about organisational phenomena.

The main difficulty here, particularly where new technology is involved, is set out by Checkland and Holwell (1998: 56):

In any developing field allied to a changing technology, there will be a relationship between the discovery and exploitation of technical possibilities (‘practice’) and the development of thinking which makes sense of happenings (‘theory’)…where the technology is developing very rapidly, new practical possibilities will be found and developed by users…they will not wait for relevant theory! Hence practice will tend to outrun the development of thinking in any field in which the technological changes come very quickly indeed, as has been the case with computing hardware and software.

The relation between domains of new organisational thinking, practices and technologies is shown in Figure 1.1.

Interpreting the significance of new technologies

First, it must be noted that existing ideas and assumptions about work and organisations, as well as corporate policies, business strategies and management philosophies, shape the way we think about new technologies – what role they might play, what new technologies would prove advantageous. Experience with previous technologies, then, may structure the way new ones are configured. For example, new technologies may simply be used to substitute for old technologies rather than facilitate new ways of working (see also McLoughlin forthcoming).1 This takes an implicit ‘constructivisť approach to technology (Grint and Woolgar 1997): what technologies can and cannot do – and the sort of work configurations to which they lend themselves – rely on ‘interpretive’ skills on the part of those deploying new technologies. In other words, technologies may be ‘read’ in different ways, with many views on their possible uses.

Figure 1.1 New organisational thinking, technologies and practices

New technologies in support of new ways of working

Second, where technologies are indeed interpreted and deployed to facilitate new forms of practice, then new organisational designs, new business processes and even new products and services may follow. But, as has been said, the ability to reconfigure organisational, technological and human resources is not straight-forward and cannot be guaranteed. The problems involved here range from managing resistance and coping with different political agendas, to acquiring or developing the skills, values and attitudes needed to make the new configurations work (McLoughlin and Harris 1997). This is particularly so where radical changes are produced that demand new methods of supervision, new relationships between peers, and new sets of responsibilities (Badham et al. 1997). Such practices, then, are bound up with new social and organisational dynamics that demand some new organisational thinking.

Developing new organisational thinking

Third, virtual working often challenges the principles that underlie management strategies and practices, as well as our basic assumptions about organisations. Where organisational values and norms are out of ‘sync’ with the new ways of working, their success is likely to be jeopardised. In the management of telecommuting arrangements, for instance, control systems and attitudes that emphasise commitment and shared values may be required (see Depickere, Chapter 7 this volume). But new thinking may also be needed to make sense of the new dynamics – for example, in identifying the issues of significance in the new situation. So far as business networking is concerned, for instance, this may mean focusing on relationship-building, securing inter-firm trust, and handling uncertainty and ambiguity (see Harris et al., Chapter 3 this volume).

Our deep-seated assumptions about organisations may also need rethinking. These often involve the way we think and talk about organisations. As Morgan (...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Management of Technology and Innovation

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Introduction: From new designs to new dynamics

- Part I: The inter- and intra-organisational level

- Part II: Individual experiences of virtual working

- Part III: Management and control in virtual working

- Part IV: Learning and innovation in virtual working