![]()

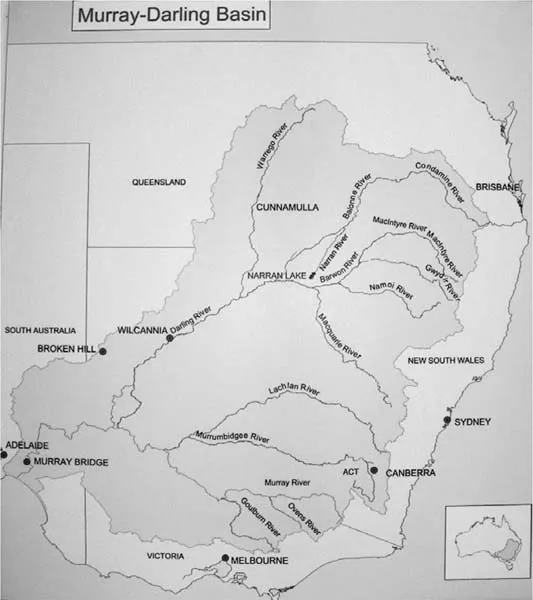

# Map 1: The Murray-Darling Basin, Australia

MAPPING THE TERRITORY1

A map is a story of Country that shapes our relationship to the known world. Maps guide our geographical explorations, near and far, and form the grounding of our thought. They are one of the most naturalized and taken-for-granted ways that our relationship to land is made. In asking how can we think about water differently, Water in a Dry Land seeks to create new maps that produce alternative stories and practices. The website connected with this book opens the possibility of thinking spatially and visually through the processes of creating these new tracings across the land.

Global Sustainability and Water

Making progress towards sustainability is like going to a new country we have never been to before. We do not know what the destinations will be like, we cannot tell how to get there. (Prescott-Allen, 2001, p. 2)

While the concept of sustainability is much criticized for its ubiquitous use and frequent association with maintaining patterns of consumption, it is the tool that global, national, and local organizations have used to initiate authentic action to address planetary problems. “Sustainability” was placed on the global agenda by the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future, delivered to the United Nations in 1987. In that report, sustainable development was defined in anthropocentric terms as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This was seen to be especially crucial in relation to environmental limitations; however, the interlinking of the social, the cultural, the environmental, and the economic was emphasized. Population and human resources, food security, species and ecosystems, energy, industry, and the urban challenge of humans in their built environment were considered as essential elements of the sustainability of social and ecological systems. The beginning of the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development followed in 2005, a culmination of decades of global mobilization for a shift in emphasis toward protecting the environment.

At the time of writing we are no closer to achieving global sustainability. Instead, we have increasing awareness of the momentum of climate change, species loss, risks to food, energy, and water security, and massive global migrations as a result of war and poverty. Scholars in a range of disciplines have taken up Paul Crutzen's term the Anthropocene to define a new geological era of human-induced changes to planetary processes: “The Anthropocene represents a new phase in the history of both humankind and of the Earth, when natural forces and human forces became intertwined, so that the fate of one determines the fate of the other” (Zalasiewicz, Williams, Steffen, & Crutzen, 2010, p. 2231). Geologically, they claim, this is a remarkable episode in the history of the planet. Paradoxically, by recognizing human agency and responsibility, this term opens the possibility for emergent responses to more sustainably connect nature and culture, economy and ecology, the natural and human sciences, in order to address escalating planetary problems (Colebrook, 2012).

In a ground-breaking paper, “The Intersections of Biological Diversity and Cultural Diversity,” 15 academics from different disciplines and global geographies use the leverage of “the Anthropocene” to map “a novel pathway towards the integration” of ecological and cultural systems (Pretty et al., 2009, p. 105). They argue that previously such systems have been considered separately from each other within different disciplinary boundaries and that we need to link biological and cultural diversity to move beyond the modernist separation of nature and culture. They note substantial evidence supporting the significance of local ecological knowledge expressed as stories, ceremonies, and discourses. Local ecological knowledge is constantly in process in relation to the natural world, and can guide a society's actions.

Pretty et al. (2009) argue that language can be thought of as a resource for nature. Cultural knowledge transmitted through language is critical because language links speakers inextricably to landscapes in ways that are often not translatable. Hence, if the language is lost, the cultural knowledge of the landscape is lost with it. Precisely as our knowledge of this connection is advancing, these complex systems linking language, story, landscape, and culture are receding. There is an absence of policy and action on these issues, and dying languages and vast knowledge bases are being lost at rates that are orders of magnitude higher than extinction rates in the natural world. The knowledges that are held in language and story potentially enable humans to live in balance with the environment without the need for “catastrophic learning in the event of major resource depletion.”

Water is one of the most urgent and extreme cases of major resource depletion. A panel of international experts states that: “The world is running out of water. It is the most serious ecological and human rights threat of our time” (Barlow, Dyer, Sinclair, & Quiggin, 2008). As we pollute water, we are turning to groundwater, wilderness water, and river water and extracting water faster than it can be replenished (Barlow et al., 2008, p. 2). Approximately 1 billion people lack access to safe drinking water and a 2009 report suggests that by 2030, in some developing regions of the world, water demand will exceed supply by 50%. The problem of water scarcity, however, is not about whether there is enough water, but how we use that water. While indigenous communities all over the world have harvested and managed water in sustainable ways throughout history (Shiva, 2002), during the first major wave of global colonization large dams and irrigation schemes were introduced to extract water to increase agricultural production for profit. The acquisition of colonies was accompanied by “a profound belief in the possibility of restructuring nature and re-ordering it to serve human needs and desires” (Adams & Mulligan, 2003, p. 23).

The practices of restructuring nature intensified during the latter half of the 20th century when new technologies and more productive crops were developed that further depended on harvesting water from most of the major rivers of the world. While these technologies have delivered increases in food production, they have failed in terms of ecological sustainability. Most of the major river systems are now in crisis (Pearce, 2006) and the water crisis is described as “the most pervasive, the most severe, and most invisible dimension of the ecological devastation of the earth” (Shiva, 2002, p. 1).

The work and learning of water has traditionally been the work of community. “In most indigenous communities, collective water rights and management were the key for water conservation and harvesting. By creating rules and limits on water use, collective water management ensured sustainability and equity” (Shiva, 2006, p. 12). The knowledge and practices of managing water sustainably—the sustainable use of water for the production of food and maintenance of all life forms—was learned in families and communities. When millions of people in indigenous communities were displaced by dams and irrigation schemes, the daily work of water to sustain life, and the knowledge associated with that work, was also displaced.

The Nile is an outstanding example of these forces at work. As the longest river in the world, it is shared by 10 African countries: Ethiopia, the Sudan, Egypt, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Eritrea. The Nile is now a complicated site of water conflict which follows the patterns of displacement of local communities and local knowledge about water (Shiva, 2002, p. 74). The massive construction of dams by the British were “the beginning of the end of the Nile,” an end that was accomplished by the Soviet Empire with the building of the Aswan Dam (Schama, 1996, p. 257). The Aswan Dam is described as having displaced 100,000 Sudanese people when it was built in 1958 (Shiva, 2002, p. 75). Most of these discourses about water are stories of irretrievable loss.

Another approach to these dire stories of loss is to seek “a way of looking; of rediscovering what we already have, but which somehow eludes our recognition and our appreciation” (Schama, 1996, p.14). Simon Schama says we do not need “yet another explanation of what we have lost,” but “an exploration of what we may yet find” (Schama, 1996, p. 14). Vandana Shiva, too, argues for “a recovery of the sacred and a recovery of the commons” in our relations with water (Shiva, 2002, p. 138). She believes that: “Sacred waters carry us beyond the marketplace into a world charged with myths and stories, beliefs and devotion, culture and celebration; [and that] each of us has a role in shaping the creation story of the future” (Shiva, 2002, p. 139). To do this means creating new stories of water, “we need new versions of these sacred myths: versions that recognize that the sacred rivers may not be so permanent after all” (Pearce, 2006, p. 350).

Water in Australia: The Murray-Darling Basin

As the driest inhabited continent on earth (Rose, 2007), Australia uses more water per head of population than any other country in the world (Sinclair, 2008). Extreme climate variations over the last several decades are believed to have been produced by global warming effects. In 2005, the year this program of research began, Australia had been in the grip of the most severe drought in the continent's recorded history (Somerville, 2008b).2 The 13-year drought brought global attention to the region in eastern Australia known as the Murray-Darling Basin, referred to in some accounts as “the nation's food basket.”

A typical map of the Murray-Darling Basin shows the coastline of the island continent now known as Australia, the boundary lines of states, the names of the major capital cities, and the major rivers with their English names. This conventional map of the Murray-Darling Basin produces an imaginary that parallels the predominance of scientific, positivist inquiry and discourses in relation to water in the Murray-Darling Basin. Despite massive resources spent on scientific research to analyze the extent and nature of the ecological problem, we do not know how to transform the way we think, and consequently act, in relation to water.

The Murray-Darling Basin covers approximately one seventh (14%) of the total area of Australia, contains two thirds of the country's irrigated lands, and produces 40% of the country's agricultural output, valued at $10 billion a year. It includes almost the whole of inland south-east Australia, extending across parts of five states: the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia. Each state is a separate governmental jurisdiction. The Basin catchment area lies west of the Great Dividing Range that marks the division between the highly populated and well-watered eastern seaboard and the drier, sparsely inhabited inland. Both ground and surface water flow west from the Great Dividing Range into the Basin. The network of rivers and their tributaries begins in the headwaters of the Balonne and Condamine Rivers in Queensland and flows down through the Narran, Culgoa, and Bokhara Rivers to the Darling, eventually joining the Murray, Australia's longest river. The Murray River travels through several lakes to enter the sea in large estuarine wetlands in South Australia.

In 1990 the Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) Ministerial Council launched a strategy of “integrated catchment management,” in response to the declining health of the system of water. Over 10 years later, they reported that water quality and ecosystem health were continuing to decline (MDB, 2001, p. 2). Significantly, they emphasized “the importance of people in the process of developing a shared vision and acting together to manage the natural resources of their catchment” (MDB, 2001, p. 1). A scoping study on Aboriginal involvement in the proposed initiatives found a “chasm between the perception of the available opportunities for involvement and the reality experienced by Aboriginal people” (Ward, Reys, Davies, & Roots, 2003). The study found, “Aboriginal people are concerned and angry about the decline in health of the Murray-Darling Basin” (Ward et al., 2003, p. 21) and that there was a strong case for involving Aboriginal people because of the “collective and holistic nature of Aboriginal people's concerns about the natural environment and their Country” (Ward et al., 2003, p. 29). The most significant barrier to Aboriginal involvement was identified as a “lack of respect and understanding of Aboriginal culture and its relevance to natural resource management” (Ward et al., 2003, p. 8).

The situation continued to decline. The Murray River was described as dying in 2007 due to decreasing flows of water downstream (Sinclair, 2008) and the Darling was reduced to a series of toxic puddles in some places, with towns threatened with loss of water supply. The Narran Lake, a Ramsar listed wetlands of international significance in the middle of the system of waters was on the verge of irreversible decline (Thoms, Markwort, & Tyson, 2008). The Murray-Darling Basin Commission proposed further draining of wetlands, building more dams and complex water trading schemes to address urgent and highly contested needs for water. Flooding rains in 2011, and again in 2012, brought some relief to the urgency, but even then when the federal government decided to buy back land and irrigation licenses, there were angry and violent protests. The question remains unchanged: How can we transform our stories and practices of water in this old dry land, and indeed globally?

Different Maps and Forms of Knowledge Production

Aboriginal people continue to inhabit all of the lands and waterways of the Murray-Darling Basin but the stories and practices through which they have survived since the last Ice Age are largely unknown in mainstream Australian culture. The processes through which this knowledge might become visible have not been developed because of fundamental paradigm differences between Aboriginal understandings of Country, and Western knowledge frameworks. A map of the Aboriginal languages of the Murray-Darling Basin offers a potential beginning point for new understandings.

Australia had over 200 distinct Aboriginal languages with around 600 different dialects at the time of white settlement. A number of linguists have mapped the distribution of these languages. Most notably Norman Tindale traveled throughout Australia to develop the first maps from extensive linguistic research and David Horton produced the most recent digital versions from archival research (see AIATSIS website). Even though these maps of the territory of Aboriginal languages are already artifacts of print literacy, they still allow us to begin to imagine the possibility of a different reality. The portion of Horton's map labeled the Riverine Language Group shows 40 patches of different colors of variable sizes and shapes outlined with an irregular line of dark pink to indicate their linguistic coherence. The pink line delineates the territory of the Riverine Language Group which overlaps almost exactly with the map of the Murray-Darling Basin. The fuzzy lines where the different patches of color meet and merge indicate that language territory boundaries are determined by complex ecological and human relations and negotiations.

The stark difference between the standard map of the Murray-Darling Basin and the map of the Aboriginal Riverine Language Group draws attention to the difference between positivist scientific research about natural phenomena and qualitative studies about people and their relationships to place and to each other. While both make important contributions to our understanding and knowledge of the world, qualitative research is grounded in an understanding of “the other” originating historically in ethnographic research.

Ethnography is at the heart of qualitative research as method. Derived from the Greek ethnos, meaning people, and grapho meaning to write, it fundamentally concerns the relationship between the study of peoples and the ways we write about them. Based in anthropology as a disciplinary field, however, ethnography emerged in parallel to the colonization of many indigenous peoples of the world. By the mid-1980s critiques were mounting about the colonizing nature of anthropological knowledge, and the impossibility for the colonizer to represent the lives of the colonized other. In response to the recognition of complicity in the processes of colonization, a fundamental critique of ethnographic practice emerged. The “death of ethnography” was announced.

The tradition of auto/ethnography sprang from this response. The ethnographic study of the self produced a wide array of diverse texts of self-experience. The tradition of auto/ethnography has yielded important methodological innovations in storytelling and art-based practice, but has been criticized for its inward looking focus. In auto/ethnography there seems to have been a retraction from the necessary, difficult, and challenging work of understanding the mutual entanglement of self and other in the constitution of subjectivity. The act of inhabiting the slash between auto, the self, and ethno, the other, is one of the most difficult things to do in research.

Another possibility is opened by researcher “reflexivity”—acknowledging, interrogating, and disrupting the presence of the researcher “I.” Enduring questions for researcher reflexivity are: Where am I in this research and how do my actions as a researcher shape the knowledge made possible through this research and its representations? As a female, Antipodean, third generation Scottish immigrant, I research in the context of the relations between Indigenous and non-In...