- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Aperture is a dedicated end-to-end workflow tool for photographers and this book guides the reader through the complete process from capture to output.

The beauty of Aperture is that - unlike Adobe's rival workflow software, Lightroom - it doesn't force a particular structure or workflow on to the user. This more open-ended approach means it is becoming increasingly popular with photographers - but also means that there is a lot to learn for a newcomer to the software.

Whether you are cataloging, organising and adding Metadata to thousands of RAW files; selecting, cropping and correcting an individual image or preparing files for final output to web or print, this book provides a complete reference for producing high-quality results with Aperture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Apple Aperture 3 by Ken McMahon,Nik Rawlinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Digital Media. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| CHAPTER 1 | |

| |

| Camera Raw | |

Introduction

First and foremost, Aperture is a Raw converter. You can use it to organize, annotate, edit and output TIFF, JPEG and other RGB file formats and it does a great job, but this is to ignore its most useful function.

Aperture’s Raw decoder is designed to help you squeeze the last ounce of quality from your digital images. From the Raw Fine Tuning controls that allow you to influence how Aperture’s decoder interprets the data in your Camera Raw files, to the tonal adjustments that allow you to recover apparently lost highlight and shadow detail, Aperture’s tools are designed primarily to work with Camera Raw files.

Knowing what Camera Raw files are, how they differ from RGB file formats like TIFF, JPEG and PSD, and how Camera Raw data are produced and stored will influence every aspect of your digital imaging workflow – from your choice of exposure to how and when you apply Sharpening to your images.

In this chapter we begin by taking a look at what Camera Raw is and the advantages and disadvantages of adopting a Raw digital imaging workflow. If you’re not currently shooting Raw, and aren’t sure that it’s for you, this information may help you come to a decision.

FIG. 1.1 The Raw Fine Tuning adjustment on Aperture’s Adjustments Inspector.

Following that we take a fairly technical look at how imaging sensors record the data in a scene and how that information is stored in a Camera Raw file. It’s not essential to know this, but it will help you make shooting and editing decisions that produce the best possible final image quality.

The second half of the chapter deals specifically with the Adjustment controls found in the Raw Fine Tuning adjustment of Aperture’s Adjustments Inspector (Fig. 1.1). These are only available when working with Camera Raw files and determine how Aperture’s Raw decoder interprets Raw data to produce an RGB image ready for further editing. If you’re new to Aperture you might want to fast forward to Chapter 2 to familiarize yourself with the workspace and how Aperture works with images and Versions before returning here.

The chapter ends with an explanation of Adobe’s DNG Raw format and the advantages it offers in an Aperture-based Raw workflow.

What is Camera Raw?

The first thing to understand about Camera Raw is that it is not one file format, but many. Camera Raw formats are proprietary, developed by camera manufacturers to best handle the data produced by individual models. Hence, the Raw file format produced by Canon’s EOS 1D Mark IV will differ from that produced by the Nikon D3S and even from other Canon dSLRs.

Though there are some important differences, Raw is just another file format, like JPEG or TIFF. The major difference is that Raw files contain unprocessed data from the camera sensor. Before Raw data can be viewed as an RGB image they have to undergo a number of processes. If you shoot in an RGB format, such as TIFF or JPEG, this processing is done in the camera. If you shoot Raw, it’s done by Raw decoder software like that used in Aperture.

Raw Support

The proprietary nature of camera Raw formats has a number of important implications for the photographer whose livelihood may depend on the integrity of and future access to a library of images.

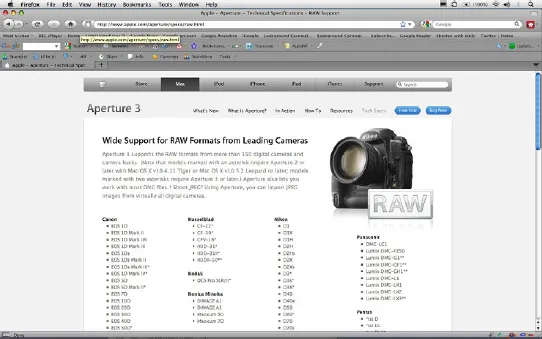

In practical terms, your ability to view and manipulate Raw files from your camera depends upon the availability of software which is able to read those files. Camera manufacturers usually supply a software utility for this purpose and, as well as MacOs X and Aperture, an increasing number of applications developed by third-party vendors now support a wide range of proprietary Raw formats. Apple maintains a list of Camera Raw formats supported by Aperture 2 on its website at http://www.apple.com/aperture/specs/raw.html (Fig. 1.2)

FIG. 1.2 You’ll find a list of all the Raw formats supported by Aperture at http://www.apple.com/aperture/specs/raw.html.

Raw file formats tend to adapt and change in order to keep pace with hardware developments. So when a camera manufacturer releases a new model it’s possible that the Raw file format will differ in some respect or other from that used on previous models.

The practical consequences of this are two-fold. Firstly, it means that if you buy a newly released camera model and shoot Raw with it, you may not be able to import those files to Aperture, or any other third-party application, until they are able to provide support for it. Given the proprietary nature of Raw formats, this process can take time. In the meantime you may be forced to rely on the manufacturer’s software to read and convert Raw files into a format that your software can handle.

A second, more long-term issue concerns image archiving. Given the pace of change of digital hardware, it’s not unlikely that in the course of, say, the next decade, you’ll own and use a variety of cameras, each with its own flavor of Camera Raw file format. At the end of that period, and for the foreseeable future beyond, it would be reassuring to know that you could rely on the availability of software to allow you to open and manipulate those images the way you can today.

Regrettably, if past history is anything to go by, this is by no means a certainty. Camera manufacturers, software companies, hardware platforms and operating systems come and go. Even assuming they are still around in 20 years’ time, how likely is it they will be willing to support a format for a camera that nobody has used for decades?

There are, however, ways in which you can future-proof your images from this risk. Simply by importing your photos to Aperture you are providing one means of defense. It’s fair to assume that Aperture’s library and vault backup files will continue to be readable by future versions of the program. Another means of ensuring future readability of your Raw files is to convert them to Adobe’s published ‘digital negative’ DNG format. This option is discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

FIG. 1.3 Support for new Camera Raw formats is provided in the MacOs operating system. Owners of recently introduced digital cameras like the Canon EOS-1D Mark IV will need Aperture 3 to handle their Raw image file format. Other cameras that require Aperture 3 include Nikon’s D3 and D3s, the Olympus E3, Sony’s Alpha dSLR range and the Hasselblad CF line of digital camera backs. You can get a full list at http://www.apple.com/aperture/specs/raw.html.

The Pros and Cons of a Raw Workflow

More and more, professional photographers are realizing the benefits of shooting Raw, as opposed to TIFF or JPEG. The fact that many dSLRs provide the option of saving both types of file from a single shot gives you the option of producing a Raw file ‘just in case’. It may be that your usual workflow involves very little image processing, that subjects aren’t difficult from an exposure point of view and that 8-bit JPEGs provide good quality images.

In such situations you might think of Raw files as an insurance policy to fall back on should the lighting turn out to have been problematic, or the White Balance off. You can correct RGB files in these circumstances, but Raw files will provide you with more options and generate a better quality end result.

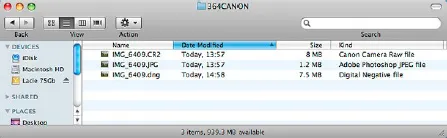

There is, of course, a downside to shooting Raw. The files are bigger than JPEGs, take longer to write and, if you’re not using Aperture, you may have to introduce at least one extra processing stage to your workflow. On balance though, we’d argue the advantages heavily outweigh the disadvantages. If you’re still undecided, the following might convince you one way or the other (Fig. 1.4).

FIG. 1.4 These three files are all from the same image shot in Raw with JPEG mode on a Canon EOS 20D. The Raw file comes in at 8MB with the JPEG occupying only 1.2MB. The third file was produced from the .CR2 file using Adobe DNG converter with lossless compression selected.

Benefits

Overall Quality

In a well-exposed image with a full range of tones that requires no processing the differences between, say, a 16-bit TIFF produced by your camera and one produced using Aperture’s Raw converter would probably be marginal. This is probably the only situation in which there is little advantage to be gained from shooting Raw, but probably not one that occurs all that regularly for most photographers.

Bit Depth

Camera Raw files use the full number of bits (usually up to 14) available in the image data. If you shoot JPEGs, this is downsampled to 8 and the camera, not you, makes the decision about how to effectively use those bits to represent the tonal levels in the image. For some images this can result in the irretrievable loss of highlight and/or shadow detail.

No Compression

Camera Raw files are not usually compressed; if they are, a lossless algorithm is employed. JPEG compression, even at the highest quality settings, removes a lot of data from your images, which can severely limit what you are able to achieve in post-processing.

Increased Latitude

Latitude describes the exposure characteristics of film emulsions or digital sensors in terms of their ability to cope with a range of light levels. When the range of light levels (called the dynamic range) in a subject is within that capable of being recorded by the film or sensor, latitude provides an indication of the degree to which the image can be over or underexposed while still producing acceptable results (i.e. details in the highlights and shadows).

In a Raw workflow, your images have greater latitude than if you’re working with RGB files. By using Aperture’s Exposure, Levels, and Highlight and Shadow tools, you can ensure that the critical tonal regions receive the most bits. In practice, this means you can pull detail from apparently blown highlights and, to a lesser degree, rescue shadow detail and produce a robust image capable of withstanding further pixel manipulation.

Future Improvements

Currently, Aperture’s R...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Camera Raw

- Chapter 2: How Aperture Works

- Chapter 3: Managing Your Images

- Chapter 4: Working with Metadata

- Chapter 5: Adjusting Images

- Chapter 6: Aperture Workflow

- Chapter 7: Working with Other Applications

- Chapter 8: Output

- Index