![]()

1 Real estate (RE)

An overview of the sector

Main sections

Learning outcomes

1.1 Definition of real estate (RE)

1.2 RE subsectors (or submarkets)

1.3 The location factor

1.4 Location and ‘authentic’ versus ‘derived’ demand for RE

1.5 Other characteristics of RE – and wider interactions

1.6 Why study RE economics?

Having gone through this chapter, a student should be able to

1 Define RE and list its main components.

2 Distinguish between ‘derived’ and ‘authentic’ demand for RE.

3 Explain how RE subsectors (or submarkets) are created.

4 List and discuss RE's main characteristics.

5 Discuss the main implications of those characteristics for (a) a cityscape, (b) financial markets and rates, and (c) the GDP.

6 Advance reasons for studying RE economics.

1.1 Definition of real estate (RE)

What is real estate (RE)? It is a name given to land, buildings, and legal rights over immovable property,1 especially when they can be priced for possible sale in an actual or potential market.2 Usually such a price reflects derived demand. The latter originates from demand for the physical good or service that is or can be produced, or sold, on a piece of land or in buildings. For example, residential land is demanded for the dwellings it can support; the dwellings, in turn, are usually demanded for the flow of ‘housing services’ (including access to work or amenities) they can generate. Agrarian land is demanded for the crop one can grow on it. Retailers demand sites as gateways to customers (see Chapter 6).

In some cases (e.g., landscapes of pristine beauty, conservation land, or monuments), land is demanded as is, i.e., for itself rather than as a means to an end. This type of land, however, is often subject to protection (meaning that its current use becomes legally exclusive of all others), and can easily become priceless too, even though one can still evaluate it in terms of opportunity cost. Of course, any such evaluation would almost certainly result in lower opportunity cost estimates than the value of land in its current state: that of an exceptionally beautiful landscape or as location of a monument, like the Acropolis of Athens, England's Stonehenge, the Taj Mahal in India, or – maybe! – Elvis Presley's Graceland mansion in Memphis, Tennessee.

1.2 RE subsectors (or submarkets)

Derived demand for RE is the rule rather than the exception. Its existence is one way whereby RE subsectors or submarkets are created.3 As an example, agrarian land competes with residential land, and the latter with commercial (offices, hotels, retail outlets) and industrial (including warehousing), since all these different land uses are defined by different goods or services, which, moreover, sell at different prices. A structure of land prices is thus created that is very much determined by the highest price that can be paid for the ‘best’ land use.

A second way whereby subsectors or submarkets come about involves the specific characteristics of land (its location, its features and properties, and its relative scarcity) and of the general environment – which means that even within the same broad land use (e.g., residential), different prices and different subsectors or submarkets will emerge (e.g., ‘good’ versus ‘bad’ neighbourhoods). A third way relates to the characteristics of buildings, giving rise, for example, to the markets for new versus old buildings. A fourth way is generated by the diversity of legally recognized property rights pertaining to RE assets. Examples of such rights are ownership versus renting versus in-between4 tenures or freehold versus leasehold (see Box 1.1). All four ways interact, creating a fluid plethora of RE subsectors or submarkets.

In this universe, the broadest possible distinction is between housing and non-housing RE. Both are extremely important. Both interact. But of course the largest part of the so-called urban environment is made up of housing, whether rented or owner-occupied. The sum of housing-related transactions constitutes the housing market.5

Box 1.1 Freehold versus leasehold

Freehold (or fee simple or fee simple absolute) is the right to own land in perpetuity (IVG, 2003).

Leasehold is the right to hold or use property for a fixed period of time at a given price, without transfer of ownership, on the basis of a lease contract (www.investorwords.com).

A lease is a contract arrangement in which rights of use and possession are conveyed from a property's title owner (called the landlord, or lessor) in return for a promise by another (called a tenant, or lessee) to pay rents as prescribed by the lease (IVG, 2003).

In the UK residential sector, a lessee who buys the freehold of the house he/she has been renting from a lessor achieves enfranchisement. So do lessees of flats who collectively buy the freehold of their building. The process creates a marriage value (an increase in the value of the property resulting from the joining of the freehold and leasehold interests), which under law is split between landlord and (enfranchised) tenant(s). Marriage value is also created from the granting of a lease extension. (For details and analysis, see www.lease-advice.org.)

Because housing submarkets obviously exist, some authors have gone as far as to ask whether it is legitimate or meaningful to speak of a single, homogenized market in housing at all (Alhashimi and Dwyer, 2004). This is perhaps too extreme; by analogy, one shouldn't speak of the market for chocolate, because there are different brands and kinds of chocolate. It is more fruitful, and also more helpful to policy makers, to determine why and how housing submarkets arise in the first place, or whether they persist over time. To this end, an interesting question is whether the definition of a housing submarket should be limited to instances where obviously different dwellings (in terms of location, the physical and socio-economic environment, and/or structural attributes) have different prices, or should be extended to instances where the same, or a ‘standardized’, dwelling, or an attribute of a dwelling, is found at different prices (see Robinson, 1979: 33–7; Jones et al., 2002; Pryce and Evans, 2007).6

Not only do housing submarkets exist (see Munro and Maclennan, 1987), but, moreover, they persist over time (Jones et al., 2002). This is not a trivial conclusion. For, in theory, price differences could be eliminated, and submarkets vanish, if developers built in high-price areas and households relocated to low-price ones (Jones et al., 2002: 3). Since this is not happening, housing submarkets can be interpreted as a measure of housing market imperfections, relating to things such as search and transaction costs, moving inertia, insufficient information, and inelastic supply, to name but some of standard economic theory's culprits. Such ‘imperfections’, however, may be inevitable, impossible to remove, and even desirable: for example, households of a certain social class may be more than willing to pay a premium for a ‘standardized’ dwelling in order to congregate away from other groups (see Kain and Quigley, 1970; Maclennan and Tu, 1996).

1.3 The location factor

The defining characteristic of RE is that it is specific to location. Again, location is usually demanded as a means to an end, but very often it is also demanded for its own sake – without in fact becoming priceless. For example, when one says, ‘I like this neighbourhood because I grew up here’, how can one separate location from what location gives one in terms of feelings or social contacts? Is this a case of demand for the item or of derived demand for what the item is associated with? In truth, the one is subsumed under the other, and an attempt at separation would be tantamount to hair-splitting, with little, if any, practical significance or implications.

What is more important is that location imparts a monopoly element, i.e., an element of ‘uniqueness’ or ‘exclusiveness’, to any particular piece of RE. The monopoly element can be weak, as when many different locations convey fundamentally the same cost (or revenue, or utility)7 advantage of access to work, amenities, feelings and social contacts, markets, suppliers, or clienteles; or, alternatively, it can be strong, as when a small number of locations (or one, at the limit) confer such an advantage.

Still, in the vast majority of cases, a RE market cannot be truly monopolized, even though any particular location can be or is so. The reason is that there usually are substitute locations to choose from; possibly at a lower land cost to the interested user, but at a higher transport cost or at a higher opportunity cost of foregone revenue or utility. Thus, the RE market is a typical example of monopolistic competition (many buyers and sellers, each seller offering more-or-less different versions of fundamentally the same good, and, therefore, extensive – even though not perfect – substitutability between RE assets).

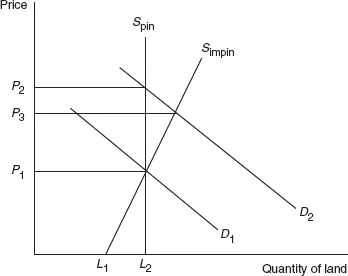

Whether weak or strong, the monopoly element exists, and is the decisive factor making the supply of land inelastic. In turn, inelastic land supply implies that increases in demand for RE will result in higher than otherwise RE prices (see Box 1.2, Figure 1.1, and Box 1.3). It also implies that price rises in RE are, most of the time, demand-, rather than supply-, driven.

Box 1.2 The supply of land is inelastic

Land's inelasticity of supply means that on any given geographical area the percentage change in the quantity of land supplied is smaller than the percentage change in land price; if no amount of change in price causes the quantity of land supplied to change, then inelasticity is perfect, and the supply of land in a typical price–quantity diagram graphs as a vertical line (see Figure 1.1).

Perfect inelasticity of land supply would occur only in two cases: (a) over land as a whole, i.e., all the land in a country or even on the planet; (b) over land at a specific location. However, the supply of land in a given area or for a specific use will usually be imperfectly inelastic, since, given the ‘right’ price, more land can be attracted away from other areas or uses. As a special case, improvements in high-rise building technology may increase the elasticity of land supply even in a vacant plot, i.e., a specific location. (‘Vacant’ here also means a plot where a standing building has exhausted its economic value.)

Figure 1.1 An increase in demand from D1 to D2 causes price to rise from P1 to P2 when supply is perfectly inelastic (Spin), but only to P3 if supply is imperfectly inelastic (Simpin).

In Figure 1.1, ...