![]()

CHAPTER 1

Arcs – Organic Movement/Natural Motion

Very few living organisms are capable of moves that have a mechanical in and out or up and down precision.

The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation – Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston

In this chapter, we’ll be looking at the basis of natural movement – arcs. Arcs are present in the majority of motions in the natural world; this is due to the effects of mass, weight, and inertia on objects, whether living or not. Think of an object traveling through the air, such as a ball being thrown; although the ball may follow a straighter line at the start of the throw, it will naturally follow more of an arc, as it loses speed and gravity takes hold. The natural phenomenon of arced motion needs to be replicated convincingly in animation to add believability, if the motion is not arced or the timing is even, it will look unnatural and the illusion will be lost.

Natural arcs can be seen in the animation exercises throughout this book. The following are some examples where you would see arcs in motion in the other tutorials exercises:

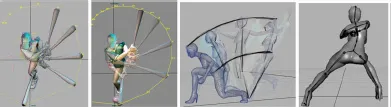

Bat Swing – In the baseball bat swing animation that we’ll look at in later chapters, a clear arced motion can be seen on the swing; this is because the bat swings from the wrist, which is a fixed pivot on the hand. This pendulum type motion is typical in human or organic motion and also applies to the limbs on the body (see Fig. 1.0.1, left screens).

Jump Landing – In the jump animation that we’ll look at in Chapter 11, there are natural arcs on the body throughout the animation, from the start through the motion in the air and on the landing. At the landing phase of the sequence, the body pivots around the foot that’s planted on the ground, with natural arcs visible on the hips and torso (see Fig. 1.0.1, third screen from left).

FIG 1.0.1 Arcs – bat pendulum swing, hip rotation, and body pose.

Character Posing – Organic arcs are also visible in the body’s form and shape in real life, even when the body is not in motion. This is due to the curvature of the spine and weight distribution on the body. Typically, the body distributes weight off center, which creates natural arced shapes running across the body (see Fig. 1.0.1, fourth screen from left).

If the body is posed with purely straight lines or blocky square shapes, the pose will look unnatural and robotic. This is something, which is common in many novice animations. Throughout the book, we will look at how to pose the body with natural arcs that give the animation weight and balance. We will look in detail at character posing specifically in Chapter 9.

Arcs in Object Motion

In the first two tutorials in this chapter, we’ll look specifically at arced motion for object animation. As in the jump animation example that we touched on, objects moving through the air should have a natural fluid arced motion due to momentum, inertia (or loss of speed), and the effect of gravity.

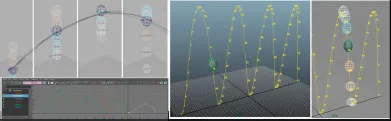

Ball Bounce – In the first tutorial, we’ll look at a ball bounce animation. Arcs are apparent in the motion in both the timing of the animation as the ball’s momentum is lost and in the motion as the ball bounces across the ground (see Fig. 1.0.2, left screens).

Plane Trajectory – In the tutorial of Chapter 2, we’ll look at a takeoff animation for an F16 fighter plane. Although the F16 fighter is being driven into the air by the rocket jets on the plane, there are still natural arcs that should be apparent on both liftoff (due to momentum and gravity) and flight as the plane maneuvers (see Fig. 1.0.2, right screens).

FIG 1.0.2 Arcs – object trajectory.

Localized Arcs – Human Motion

The third and fourth tutorials in this chapter will focus specifically on arcs in human motion. For these exercises, we will look at arcs on a couple of localized areas on the body. These tutorials will introduce common character animation concepts including posing and Inverse Kinematics.

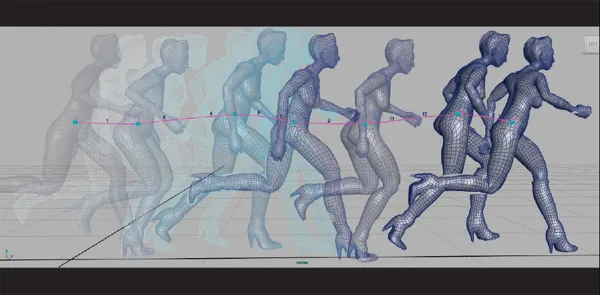

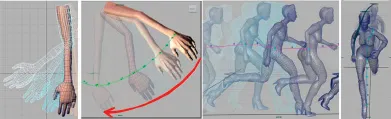

• In the arm swing tutorial, we will look at the pendulum swing on the arm; in addition to analyzing the arc on the arm swing, we will also touch on a couple of other principles of animation including follow-through and Ease In & Ease Out to mimic real-world motion through animation (see Fig. 1.0.3, left).

• In the run cycle tutorial, we will look specifically at the arc on the hip trajectory in the animation. The natural arc of the hips during the weight shifts and foot plants on the run is key in creating believability in the run cycle (see Fig. 1.0.3, right).

FIG 1.0.3 Arcs – localized human motion.

Chapter 1.1 – Animation Test – Bouncing Ball

The bouncing ball animation test was originally used at Disney as a test of skill for new animators joining the studio. The test is still in use today at studios including Pixar:

no matter how seasoned you are, this is the first thing that an animator would do when they come into Pixar, because it shows timing, spacing, squash and stretch, anticipation, etc.

Andrew Cordon, Senior Animator, Pixar – 3D World Issue 130, June 2010, p. 24.

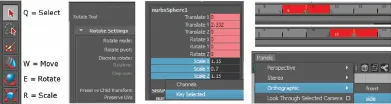

In this tutorial, we’ll be focusing initially on creating fluid blocked in movement for the ball bounce through the standard manipulation and hand-keying tools in Maya. The tutorial will first introduce you to the fundamentals of creating and editing animation in Maya including the following: Animation Preferences, the Channel Box (for viewing motion values) Transformation tools for manipulation, keyframing, and playback controls (see Fig. 1.1.01).

FIG 1.1.01 Animation basics – Transform Tools, Channel Box, Keyframes, and Orthographic View.

Other key animation principles including Ease In & Ease Out, Squash and Stretch, and Timing & Spacing will also be introduced with the use of key edits using the Time Slider, Channel Box, and Maya Graph Editor to edit motion timing. The Maya Motion Trail feature will also be utilized alongside display ghosting to validate the final arc on the ball bounce as well as the timing intervals (see Fig. 1.1.02).

FIG 1.1.02 Animation ghosting, the Graph Editor, and Motion Trail.

Animation Preferences

For our animation of the bouncing ball, we’ll work on an initial bounce cycle that can be looped. For a ball bouncing, this would be less than 1 second, with the time varying based on the height of the bounce and mass of the ball.

For the length of the animation sequence and playback rate, this can be set from Maya’s animation preferences. Let’s take a look at how to set up animation and playback range within Maya:

• Open a new session of Maya or select File > New Scene to clear the current scene.

• The preferences for Maya’s frame range can be set from a few different places:

• Animation Preferences button – This is at the bottom right corner of the user interface; it is th...