Chapter 1

African American Language

So good it’s bad

It was way back in The Day. I found myself on a hotel elevator alone with a famous National Basketball Association (NBA) superstar that I thought was the most beautiful man in the world. He was in town for a game. I was there for a national convention. He noticed my name tag and said, “So, you’re an English teacher?” Ah, my chance I thought, as I answered “Yes” in what I hoped was my most charming tone of voice. Then he said, “I better watch my grammar!” I hastened to reassure him: “No, YOU don’t have to watch anything.” But this fine baller ignored my lil attempt at mackin. Instead, he went on to tell me about how, in high school, his English teacher had always been on him about his grammar. He then proceeded to relate this looooooooong story about his struggle to learn the distinction between “who” and “whom.” It was clear that this beautiful Brotha’s whole experience with language in school brought back painful memories. As I listened, I just wanted to say: “Hey, forget about “who” and “whom.” Let’s talk about two other pronouns—“you” and “me”.

(Smitherman, forthcoming)

Since the time I joined the Academy and entered the lists of the Language Wars, I have often thought about Mr. Fine Baller. He had not only graduated from high school, he had also gone on to college before being drafted into the NBA. But for every Brotha like him, there are many thousands gone.

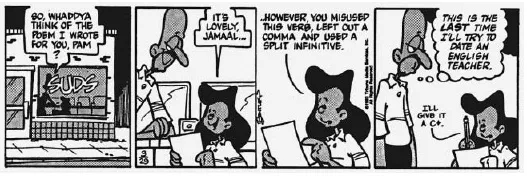

Figure 1.1 “Herb & Jamal” cartoon, by Stephen Bentley.

B.J … substitutes “who” for “whom.” And he can’t get his mouth ready for them readers written in a language all their own and talkin bout no news wouldn’t none of us kids want to play with anyhow. And time he express himself his own way, teacher jump in his chest ranting, “Don’t say ‘I don’t have no homework.’ Don’t you realize that two negatives make a positive? So you mean in fact that you do have your homework.” And B.J. know exactly what he mean and so do she. So they send him to … the speech correction officer or whatever his title is. And the creep ask a lot of dumb questions most which ain’t none of his business and then jump nasty behind B.J. brief replies and threaten to do B.J. dirty in that dossier. Sure enough he write the whole thing up in the school record. And come to find out B.J. verbally destitute. Got no language skills to speak of and mayhap no IQ. This same B.J. the neighborhood rapper. Mouth they call him since he was a little kid tellin tales on the stoop. Mackman the big guys call him cause he writes tough love letters for them. Bottom they call him in the projects he so deep … Who in his darin and inspired wordplay rival the beautifulest brothers freakin off on the basketball court with prowess that caint even be talked about less the language bust but B.J. do it. B.J. verbally destitute. And B.J. liable to find his behind in one of them special classes takin them special pills schools recommendin these days for students who don’t act specially right.

(Bambara, 1974)

In mid-June, 2004, throughout the State of Michigan, and especially in the metro Detroit community, folks were celebrating the Detroit Pistons’ victory in the NBA Finals, their first championship in fourteen years. The word, heard everywhere, from all mouths, whatever their ethnicity, age, gender, or social class was “Deee-troit.” The City’s metropolitan dailies headlined stories about the Pistons’ big win over the favored Los Angeles Lakers, with phrases like “Deee-troit Style” (Detroit Free Press). Even Detroit baseball fans and sports announcers got all up in the Deee-troit mix: “And wasn’t that Comerica’s [Detroit baseball stadium] public address announcer who at one point bellowed: ‘Dee-troit ba-a-se-ball!’” (Henning, 2004). Yet legions of Black folk who shift the stress pattern in words like “Detroit” and “police” (“PO-lice” in Black Language) have long been branded and castigated for such pronunciation. Now “Deee-troit” is on its way to becoming the linguistic norm.

“Don’t nobody don’t know god can’t tell me nothin!”

(From a middle-aged Traditional Black Church member)

We Black folks be knowin we got some unique patterns of language goin on up in here in the U.S. of A. Yet, still today, in the twenty-first century, after more than four decades–count ’em, foe decades!—of research by language scholars, it’s some people who say Black Language ain nothin but “slang and cuss words,” or “it’s just broken English.” Not to mention those who be sayin ain no such thang as Black Language! Well, I guess it’s always gon be some folk don’t believe fat meat is greasy. Dem’s the ones gon be left behind in the dustbin of history.

Black or African American Language (BL or AAL) is a style of speaking English words with Black flava–with Africanized semantic, grammatical, pronunciation, and rhetorical patterns. AAL comes out of the experience of U.S. slave descendants. This shared experience has resulted in common speaking styles, systematic patterns of grammar, and common language practices in the Black community. Language is a tie that binds. It provides solidarity with your community and gives you a sense of personal identity. AAL served to bind the enslaved together, melding diverse African ethnic groups into one community. Ancient elements of African speech were transformed into a new language forged in the crucible of enslavement, U.S. style apartheid, and the Black struggle to survive and thrive in the face of dominating and oppressive Whiteness.

Kitchen became not only the name of the room for cooking and eating, but also the hair at the neckline, very tightly curled, typically the most African part of Black hair. Yella/high yella, red/redbone, light-skinnded became references to light-complexioned Africans. Ashy was used to refer to the whitish appearance of Black skin due to exposure to wind and cold weather. Loan translations from West African languages were maintained, like the Mandingo phrase, a ka nyi ko-jugu, literally, “it is good badly,” that is, it is very good, or it is so good that it’s bad!

The Africanization of U.S. English has been passed on from one generation to the next. This generational continuity provides a common thread across the span of time, even as each new group stamps its own linguistic imprint on the Game. Despite numerous educational and social efforts to eradicate AAL over time, the language has not only survived, it has thrived, adding to and enriching the English language. From several African languages: the tote in tote bags, from Kikongo, tota, meaning to carry; cola in Coca-Cola, from Temne, kola; banjo from Kimbundu, mbanza; banana, from Wolof and Fulani. Even the good old American English word, okay, has African language roots. Several West African languages use kay, or a similar form, and add it to a statement to confirm and convey the meaning of “yes, indeed,” “of course,” “all right.” For example, in Wolof, waw kay, waw ke; in Fula, eeyi kay; among the Mandingo, o-ke.

The roots of African American speech lie in the counter language, the resistance discourse, that was created as a communication system unintelligible to speakers of the dominant master class. Enslaved Africans and their descendants assigned alternate and sometimes oppositional semantics to English words, like Miss Ann and Mr. Charlie, coded derisive terms for White woman and White man. This language practice also produced negative terms for Africans and later, African Americans, who acted as spies and agents for Whites–terms such as Uncle Tom/Tom, Aunt Jane, and the expression, run and tell that, referring to traitors within the community who would run and tell “Ole Massa” about schemes and plans for escape from enslavement. It was a language born in the crucible of Black economic oppression: tryna make a dolla outta fifteen cent–or to cast that age-old Black expression in today’s Hip Hop terms, tryna make a dolla outta 50 cent. This coded language served as a mark of social identity and a linguistic bond between enslaved Africans of disparate ethnicities, and in later years, between African Americans of disparate socioeducational classes. Today African American Language, which may also be labeled U.S. Ebonics, is all over the nation and the globe.

From enslavement to present-day, Africans in America continue to push the linguistic envelope. Even though AAL words may look like English, the meanings and the linguistic and social rules for using these words are totally different from English. The statement, “He been married” can refer to a man who is married or divorced, depending on the pronunciation of “been.” If “been” is stressed, it means the man married a long time ago and is still married.

Little first-grade Kesha’s response to her teacher’s query about Mary’s whereabouts–“She be here”–does not mean “She is here.” In fact, ignorance of how the verb “be” functions in AAL can be a major source of miscommunication in classrooms of AAL speakers. Check it:

Teacher: Where is Mary?

Kesha: She not here.

Teacher: (clearly annoyed) She is never here!

Kesha: Yeah, she be here.

Teacher: Where? You just said she wasn’t here.

In AAL, “be” does not refer to any particular point in time. Rather it conveys the meaning of an event or action that recurs over time, even if intermittent. Thus Kesha’s “Yeah, she be here” means that Mary is in class at times even though she is not there at the present moment.

Back in The Day “The Greatest,” Muhammad Ali, speaking publicly while in East Africa, caused much consternation in whitebread, non AAL-speaking U.S. with his comment, “There are two bad White men in the world, the Russian White man and the American White man. They are the two baddest men in the history of the world.” When Ali made this pronouncement, he was using the word “bad” in a particular way, and he was speaking in a Black culturally approved rhetorical style. His reference to the two “bad White men” was a metaphor that captured the powerful status of what was then the world’s only two super powers. Ali did not mean that the Russian and the American White man were “evil,” or “not good,” nor was his commentary insulting. On the contrary, it was an expression in awesome recognition of the world-wide omnipotence of the two countries in which these symbolic White men were

citizens. Such examples of Black Language rules and speaking practices illustrate the bilingualism of African Americans—or, at the very least, demonstrate that Blacks are what linguist Arthur Palacas (2001) has called “bi-English.”

Generational continuity is important to understanding the relationship between language and race. On the one hand, race does not determine what language a child will speak, there is no such thing as a “racial language,” and no race or ethnic group is born with a particular language. Children acquire their language from the community of speakers they play, live, grow up, and socialize with. This process of acquiring language and learning to speak is a universal fact of life characteristic of human beings throughout the world. Thus, regardless of a child’s race or ethnicity, she will acquire and speak the language of her community, whether that language be the Zulu spoken in South Africa, the French spoken in Paris, the Efik spoken in West Africa, the Spanish spoken in U.S. Latino/a communities—or the African American Language spoken on the South Side of Chicago.

On the other hand, since communities in the U.S. have been separated and continue to exist along distinct racial lines, language follows suit. An African American child will more than likely play, live, grow up, and socialize in any one of the numerous African American communities of the U.S. and thus will acquire the African American Language of her community. In the same way, a European American child will more than likely play, live, grow up, and socialize in any one of the numerous European American communities of the U.S. and thus will acquire the European American English of her community. Same process of generational continuity for the Zulu child in South Africa, the French child in Paris, the Efik child in West Africa, and the Latino/a child in the U.S. Even though race does not determine what language a child will speak, race does determine what community a child grows up in, and it is that community which provides the child with language. Of course this process accounts only for the primary or first language of a child, what Old Skool linguists call the “mother tongue.” The process does not preclude the possibility of a child learning an additional language, or languages, in the process of schooling or growing up. Such bi- and multilingualism is the norm in societies beyond the borders of the U.S. And it is a vision and a worthy goal for future generations of American youth.

Linguistic push-pull

Borrowing from DuBois’s concept of “double consciousness, “I coined the term “linguistic push-pull” back in the 1970s to characterize ambivalence about what was then called “Black English.” In that famous passage from The Souls of Black Folk (1903), DuBois stated:

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

Linguistic push-pull: Black folk loving, embracing, using Black Talk, while simultaneously rejecting and hatin on it—the linguistic contradiction is manifest in both Black and White America. Of course we done come a long way from the 1970s when Black leaders like Roy Wilkins, representing the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), railed against the language spoken by millions of Black people as well as the emerging research by linguists and educators who showcased the systematic nature of “Black English.” Indeed, in that era, educational programs that acknowledged even the existence of this language were lambasted, even though such programs always had as their goal the teaching of the Language of Wider Communication (LWC) in the U.S., that is, “standard American English.” But peep this: the LWC ain decreed by the Divine One from on High. Naw, “standard American English” is a form of English that gets to be considered “standard” because it derives from the style of speaking and the language habits of the dominant race, class and gender in U.S. society.

In 1971, the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, billing itself as “a record of the darker races” (how bout dat?) published an editorial essay attacking linguist-educator Carol Reed and her colleagues in the Language Curriculum Research Group at New York’s Brooklyn College. These language educators, with funding from the Ford Foundation, had launched SEEK (Search for Elevation, Education and Knowledge), an instructional program designed to teach students college level writing skills by contrasting the differences between the students’ “Black English” and the language required in college writing. I still rate SEEK as the most creative and educationally sound language education program for AAL-speaking college students that has ever been developed. (Big ups to Carol Reed, Milton Baxter and all they peeps that worked in the SEEK Program.) The Crisis editorial, as well as Wilkins in his pronouncements in Ebony magazine and in other Black media venues, dismissed SEEK as “black nonsense.” The editorial argued that these Black Brooklyn College students’ language is

merely the English of the undereducated . . . basically the same slovenly English spoken by the South’s under-educated poor white population . . . It is time to repudiate this black nonsense and to take appropriate action against institutions which foster it in craven capitulation to the fantasies of the extreme black cultists and their pale and spineless sycophants.

(p. 78)

Wild-ass, reactionary isht like this sounded the death knell for SEEK, and its initial success with New York Black students was short-lived.

Wonder what Wilkins and company would think of today’s positive response to “Deee-troit.” To say nothing of the thousands of other examples of Black linguistic crossover into mainstream English–from the ever-popular Black “high five” that can be seen everywhere in White America, to words like “phat” and “bling-bling,” now comfortably housed in standard dictionaries of American English. This linguistic crossover notwithstanding, our society continues to reflect linguistic push-pull. Check it: in the same city now linguistically embracing “Dee-troit,” a young Black female journalist who was a volunteer writing coach in a Detroit middle school, bemoaned the language of the students:

Jelon . . . read his story with a nervous smile. He ended with, “It was off the hizzee foe shizee,” street talk for “It was fun.”

“Did he say ‘Off the hizee?’” I asked in shock.

“What’s wrong wit’ that?” Donna replied.

Donna . . . was quick-witted, one of the smartest kids I met . . . Donna’s language was that of the school, but the children didn’t just speak broken English. They wrote that way, too.

I dubbed Kayla the Period Assassin . . . Her ice cream story was coherent, but she used phrases such as “she be doing that” and used “and” or “so” to create unending sentences.

Like many of her peers, she focused on spilling her imagination onto the page, not attending to her punctuation.

(Pratt, 2004)

Here is an inner city classroom, in a school that has been labeled “failing” in this “No Child Left Behind” era, in which Black students are not moaning about writing and are not experiencing the terror of the blank page, but are, by Pratt’s own account, enthusiastically “spilling [their] imaginations” onto paper. Yet this journalist turned writing coach is bemoaning the use of “she be doing that,” obviously unaware that this use is grammatical in African American Language. In fact, this “showcase variable,” as linguist John Rickford has dubbed it (1999), has become a linguistic icon in AAL, differentiating the competent speakers of the language from the wanna be’s who always tryna bite the language. Functioning within the semantic parameters of aspect, Kayla’s use of “be” incorporates past, present and future simultaneously, conveying the meaning that whatever “she” is doing, it is characteristic of her— even though she may not be “doing” the thing at the particular moment that Kayla is speaking. Furthermore, the focal point of instruction in Pratt’s class is on punctuation and other low-level matters of form, rather than content, creativity, critical thinking, and style of expression. Pratt needs to take a page from her own writing, which is profoundly dynamic and engaging—and it ain got nothin to do wit...