Chapter 1

PROCESSES

Introduction

More than two-thirds of the Earth’s surface is covered by water, yet less than 3% of it is available on land at any one time to provide the means of landscape evolution and support life. It has long been clear that the water which flows down rivers to the sea must somehow return to the land for these processes to continue and from this has evolved the concept of the hydrological cycle.

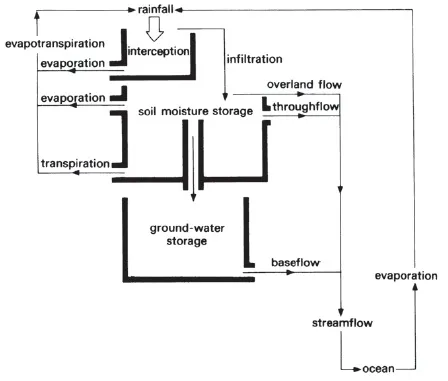

We can begin with the oceans, the great storage elements of the cycle. Evaporation from them provides the moisture for cloud formation and hence precipitation. Then, from the moment water reaches the land as rain to the moment it returns to the sea, it is engaged in a sort of obstacle course in which only a certain percentage reaches its goal. Much is returned direct to the atmosphere by evaporation, while some is held in various temporary stores such as soil or rock. Because of this it is often convenient to consider the land-based part of the hydrological cycle as a linked series of cascading reservoirs, each with a limited storage capacity (Fig. 1.1). It is the role of the hydrologist to attempt to understand each part of the hydrological cycle, but with an emphasis on those parts that are most directly connected with the land.

Precipitation

The land-based part of the hydrological cycle begins with a study of precipitation which, although largely within the province of meteorology and climatology, is introduced here in order to explain many runoff processes.

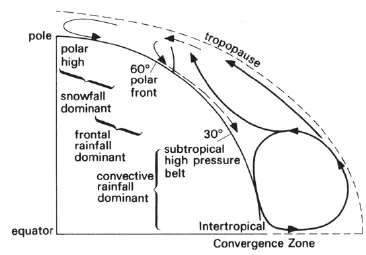

All precipitation results from atmospheric cooling and subsequent condensation of water vapour. Usually such cooling happens either at the frontal zones of depressions, or because of convection, or because an air mass is forced to rise over an area of high land. In addition the amount and distribution of precipitation depends on the global atmospheric circulation. Some regions, such as the Sahara and Antarctica, experience very little precipitation as they are permanently under the influence of the high pressure zones of the global circulation (Fig.1.2). Continental interiors such as the south-west of the USA, and central Europe, which are away from the main areas of high pressure, often become very hot in summer and produce conditions just right for convectional instability. The resultant storms are important hydrologically because of their very high intensity, localised occurrence and short duration. More persistent areas of instability occur under the influence of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and convective storms become a daily phenomenon.

Figure 1.1 The land-based part of the hydrological cycle can be thought of as a series of storage units. As each store fills after rainfall, water cascades to the next unit, eventually reaching the sea.

Figure 1.2 The general global circulation determines where rain will fall and its dominant form.

In the middle latitudes precipitation mainly results from the passage of fronts. These provide a much more uniform regime than do convectional storms, with precipitation generally of low intensity and frequent occurrence. Nevertheless within frontal systems there are usually convective cells giving higher precipitation intensities and it is such variations that often make frontal storms so complex. Further precipitation in such regions is provided by small convective showers which form in unstable polar airstreams.

The main effect of upland is to force an air mass upwards thereby promoting cooling and condensation, even without frontal or convective uplift, which increases the frequency of precipitation.

But whether precipitation is caused by fronts, convection or relief, there is often a marked seasonal pattern in the regime and this gives river flow a corresponding seasonality. Such effects are primarily caused by a shift of atmospheric circulation patterns on a global scale with the attitude of the sun as it moves between the Tropics. Such seasonality is particularly pronounced in tropical areas where the ‘wet’ season corresponds to the influence of the ITCZ and the ‘dry’ season to the subtropical high pressure belt.

Ice crystals (snowflakes) fall from most clouds in middle and higher latitudes even in summer. However the form they take by the time they reach the ground is determined by the temperature of the air through which they fall. Thus in summer, high air temperatures cause melting and rain falls, but in winter there is a greater likelihood of snow, especially in continental interiors where temperatures are very low.

It is important to understand that there is a fundamental hydrological difference between snowfall and all other forms of precipitation. This is because snow usually remains on the land surface for a long time after it has fallen; it frequently drifts; and it is only available to the hydrological cycle during spring melting. By contrast all other types of precipitation are more or less immediately available. Rainfall is measured in millimetres depth of accumulation in a specified time period. Snowfall is converted to rainfall equivalent.

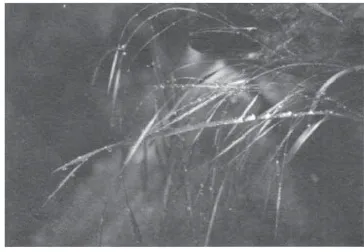

Figure 1.3 Rainfall interception on leaves.

Interception

When precipitation reaches the ground, it is intercepted by a great variety of dry surfaces which need to be thoroughly wetted before they will transmit water (Fig. 1.3). The importance of interception varies considerably depending on factors such as surface roughness. In the case of a forest cover, there are also many levels of surface to be wetted because drips from the upper wetted leaves will largely be intercepted in turn by lower leaves (Table 1.1). This is, of course, why rainfall takes such a long time to reach the ground beneath trees. By contrast in urban areas there is much less loss as the surfaces are smooth (roofs, roads, etc.). However in all circumstances it is the first part of the precipitation that will be lost to interception and this is a fixed amount for the surface concerned. After this initial loss all further precipitation will be shed so that it is relatively insignificant in a long storm but very important in a short shower. Again, because of high evaporation rates in summer, surfaces dry very quickly so that there is a full interception loss for each new shower. In winter, with lower evaporation rates, surfaces dry only slowly and a full interception loss may not occur with each new precipitation event. Interception loss is measured in millimetres per storm event.

Table 1.1. Interception and evapotranspiration losses for a mature spruce forest, Thetford, Norfolk (1975)

Evaporation and transpiration

Whenever unsaturated air comes into contact with a wet surface, a diffusion (or sharing) process operates. This process, evaporation, happens at the surfaces of lakes, rivers, wet roads, and even raindrops as they fall from clouds. When the water body is not large, as in the case of water intercepted by road surfaces, it may be evaporated completely and quickly, leaving the air still unsaturated. Precipitation leaving the cloud base also loses mass but it usually falls too quickly to be entirely evaporated. Evaporation is measured in millimetres per time period in the same way as precipitation (e.g. mm/h).

The rate of evaporation is dependent on several factors, the most important being a source of energy for vaporisation. This is largely supplied by solar radiation which is at a maximum in summer, making evaporation take place more quickly in summer than in winter. In addition, warm air will hold more moisture than cold air, and dry air will take up moisture faster than wet air. However, if air remains completely still over a wet surface, the air soon becomes saturated and no further evaporation takes place. Wind is therefore needed to bring fresh, unsaturated air into contact with the wet surface.

Evaporation takes place continually from a lake or a river and this is the maximum continual loss of water possible—the potential evaporation. However in most cases the surface area covered by water is small and most evaporation takes place from soil and plant surfaces. Water is not easily transferred from the soil body to the surface, so the surface quickly dries out. After this, although some evaporative loss does occur, it is well below the potential rate and is of minimal significance (except in arid environments).

In most humid regions the proportion of the land surface subject only to evaporation is small; for most of the year soil surfaces are covered by vegetation and in these circumstances transpiration will be the major factor determining total losses of water from the land surface. Transpiration is the process whereby water vapour escapes from living plants mainly by way of leaves. This loss of water through plant surfaces is replenished by water being drawn up through the plant tissues from the root hairs which are in contact with soil water. Transpiration is a very powerful process because it draws upon the reserves of water stored in the soil pores at depth and is in direct contrast to evaporation which simply dries out the soil surface.

The factors controlling the rate of transpiration are similar to those for evaporation. In addition, however, there are controls exerted by the soil and the plant itself. There is still no general agreement about the exact nature of the factors controlling plant transpiration, but it seems that water can move freely to leaves only if there is an unrestricted supply available to the roots. This does not mean that the soil has to be saturated, but clearly as moisture is lost from soil pores fewer roots will be in contact with water and supply to the plant will be restricted. Transpiration is really a ‘leakage’ from leaves over which many plants have very little control. As a result it continues at near the potential maximum rate until a stage of soil moisture deficiency is reached when the uptake of water no longer balances transpiration. After this the difference has to be obtained from within the plant itself and this causes wilting. The wilting point corresponds to a very low soil moisture value which is not often reached in humid regions except on very shallow or permeable soils. However in arid and semi-arid regions the wilting point would regularly be reached in plants unadapted to the prevailing conditions and so indigenous plants have special leaf configurations (e.g. cacti). Special leaf forms and the general scarcity of vegetation make the role of transpiration very much less important in arid and semi-arid regions.

Clearly it is very difficult to separate evaporation from transpiration, so the term evapotranspiration is used to describe the combined effect of the two as they influence storage of precipitation in the soil. This total loss by evapotranspiration is of major importance and may account for about threequarters of all precipitation in a year, even in humid regions.

The role of evapotranspiration in the terrestrial part of the hydrological cycle may thus be summarised as the progressive loss of soil moisture to a degree far beyond that which would occur through gravity drainage alone. A moisture deficit is thus created which has to be replenished before any fresh rain water is available for the runoff process. This replenishment takes time and is partly responsible for the lag between rainfall and runoff. Finally it is necessary to stress that the importance of evapotranspiration is dependent on a number of climatic factors and so, although clearly at a maximum in summer, losses are very variable (Table 1.1).

Infiltration, throughflow and overland flow

When precipitation has completely wetted any vegetation, the remainder is available to wet the soil or to run off over the surface (overland flow). The process whereby water enters the soil is called infiltration and it is normally measured in centimetres depth of water per time period.

Soil acts as a sort of giant sponge containing a labyrinth of passages and caverns of various sizes. The total space available for water and air is called porosity and is expressed as a percentage of the soil volume. Some of the passages and caverns (soil pores) are interlinked, although others are culdesacs and conduct no water. The passage of water from soil surface to stream bank or waterconducting rock (aquifer) thus takes place in a very tortuous way through small-diameter passages, so it is not surprising that water movement is slow. The speed of conduction of water is determined by the proportion and size of the interlinked waterfilled pores. If all pores are full, the soil is said to be saturated and the plane defining the upper surface of the saturated zone is called the water table. Figure 1.4 shows the soil saturated for a depth H above a plane XY. Under these conditions the speed of water movement varies directly with H (the hydraulic head) and is related to ...