The Modern Period Room

The Construction of the Exhibited Interior 1870–1950

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Modern Period Room

The Construction of the Exhibited Interior 1870–1950

About this book

With contributors drawn from a broad range of disciplines, The Modern Period Room brings together a carefully selected collection of essays to consider the interiors of the modern era and their more recent reconstructions from a variety of different viewpoints.

Contributions from leading design historians, architects and curators of the history of the domestic interior in the UK engage with the issues and conventions surrounding the modern period room to expose the conflicting tensions that lie beneath the conceptual and physical strategy of the modern period room's representational technique. Exploring themes and examples by prestigious architects, such as Ernö Goldfinger, Truus Schroeder and Gerrit Rietveld, the authors reveal the specific coding of presented interior spaces.

This illustrated new take on the historiography of twentieth century show interiors enables historians and theorists of architecture, design and social history to investigate the contexts in which this representational device has been used.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

The modern period room –

a contradiction in terms?

Jeremy Aynsley

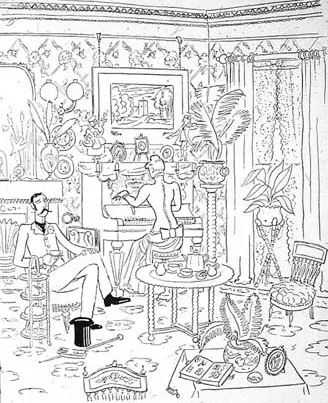

In 1939, the British cartoonist Osbert Lancaster (1908–86) published Homes Sweet Homes. This book confirmed, if confirmation were needed, that conventions of interior decoration were fully understood and the idea of a period room could become a topic of humour broadly understood by the general public. As his well-known illustrations reveal, Lancaster was keen to connect people’s choice of interior design with lifestyle – there was an assumption that manners and interiors could be associated and in so doing, he demonstrated their comic potential. In the context of the outbreak of the Second World War, Lancaster wrote:

Lancaster’s gender bias aside, his choice of categories can be taken as symptomatic of a broader understanding of how the domestic imagination could be captured in an assured and acutely rendered graphic style for popular consumption. In his book, Lancaster took familiar period styles such as Rococo, Regency and Art Nouveau, and combined them with more finely tuned terms, such as Greenery Yallery, a term that poked fun at the Aesthetic Movement, the Earnest Eighties and those of his own invention, such as Stockbrokers’ Tudor, coined for the first time in this volume. And in terms of the modern, he had no problem bringing his series up to date with ‘the modernistic’, ‘the functional’ and what Lancaster called ‘the even more functional’, which in this case, was an air-raid shelter (Figure 1.1).

From Homes Sweet Homes, John Murray, London, 1939

Museological conventions

In the field of museums, the period room ended the twentieth century with an ambivalent press. For example, in his introduction to the volume Period Rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1996, the museum’s director Philippe de Montebello wrote:

In this extract, we immediately encounter the two key issues that recur in the commentaries on the period room – authenticity and preservation. Extending this commentary, Christopher Wilk, Keeper of the Collection of Furniture, Fashion and Textiles at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), has suggested that the acquisition of period rooms by the museum has been informed by a number of impulses.6 Broadly, these fall into four categories, not mutually exclusive; first are those rooms that demonstrate histories of style, or conform to the collecting trends in the decorative arts, usefully demonstrating characteristics in other furniture forms in a total arrangement. Second, the museum has acquired rooms saved from structures about to be demolished or threatened by their owners. A third category Wilk outlined are those rooms that tell national stories; so, for example, the history of the English interior at the V&A. Finally, certain rooms illustrate particular decorative techniques, such as gilding or panelling, which are of special interest to decorative arts specialists.

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustration Credits

- Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Modern Period Room – A Contradiction In Terms?

- Chapter 2: Interiors Without Walls: Choice In Context At MoDA

- Chapter 3: Stopping the Clock: The Preservation and Presentation of Linley Sambourne House, 18 Stafford Terrace

- Chapter 4: The Double Life: The Cultural Construction of the Exhibited Interior In Modern Japan

- Chapter 5: The Restoration of Modern Life: Interwar Houses On Show In the Netherlands

- Chapter 6: ‘A Man’s House Is His Art’: The Walker Art Center’s Idea House Project and the Marketing of Domestic Design, 1941–7

- Chapter 7: Domesticity On Display: Modelling the Modern Home In Post-War Belgium, 1945–50

- Chapter 8: Kettle’s Yard: Museum or Way of Life?

- Chapter 9: Two Viennese Refugees: Lucie Rie and Her Apartment

- Chapter 10: The Preservation and Presentation of 2 Willow Road for the National Trust

- Chapter 11: Photographs of a Legacy At the Dorich House Museum

- Bibliography