- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

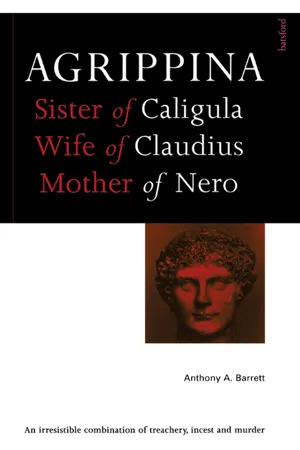

In this dynamic new biography - the first on Agrippina in English - Professor Barrett uses the latest archaeological, numismatic and historical evidence to provide a close and detailed study of her life and career. He shows how Agrippina's political contribution to her time seems in fact to have been positive, and that when she is judged by her achievements she demands admiration. Revealing the true figure behind the propaganda and the political machinations of which she was capable, he assesses the impact of her marriage to the emperor Claudius, on the country and her family. Finally, he exposed her one real failing - her relationship with her son, the monster of her own making to whom, in horrific and violent circumstances, she would eventually fall victim.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Agrippina by Anthony A. Barrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1: Background

The republic that was established in Rome after the expulsion of its kings, an event traditionally dated to 510 BC, served its purpose well for some four centuries. But its final century was one of increasing chaos and disorder. The growth of an overseas empire, in particular, created opportunities and temptations too attractive for most to resist, and the political scene was dominated by a succession of military commanders with their own excessive personal ambitions. The most famous of these commanders was without doubt Julius Caesar, whose assassination in 44 BC heralded the republic’s end.

Caesar belonged to a distinguished family, the Julians, whose name would be invoked repeatedly by generations of his successors. In the funeral oration that he gave for his aunt Julia in 68 BC he reminded his audience of the tradition that the Julian gens had existed since the foundation of Rome and was descended from the goddess Venus, through her son Aeneas and her grandson Julus, a happy fiction that was later to be given a veneer of respectability by the poet Vergil in his great national epic, the Aeneid. The Julii attained prominence in the fifth and fourth centuries, but then, despite their splendid divine ancestry, sank into obscurity for 200 years. By the time of Caesar they had once again come to prominence.1

Caesar’s ultimate political ambitions are something of a mystery, and whether or not he aimed at the restoration of a monarchical system is far from clear. But it was nature that denied him the ultimate satisfaction of a monarch, that of being succeeded by his own son. He married several times and had a reputation among his soldiers for sexual prowess but despite all these assets he produced only one legitimate child, a much-loved daughter, who on her death left no surviving offspring. Caesar’s sister Julia did better, with two granddaughters and a grandson, Octavius. This sickly and unprepossessing youth was Caesar’s closest male descendant. He was destined to change the course of history.

The custom of great Roman families who faced extinction through a lack of male heirs was the very practical one of simply acquiring a son from another prominent family. Hence Caesar adopted his great-nephew Octavius, who in the Roman manner assumed his adoptive father’s name, technically followed by a modified form of his own, Octavianus (although he in fact avoided use of this final part of his name, which would have drawn attention to his adopted status). Few men can be said to have used their inheritance more effectively than did Octavian. Styling himself the son of the deified Caesar, he made claim at the age of 18 not only to his adoptive father’s estate but also to his political legacy.

The fact that the republic was now little more than a fiction was demonstrated just over a year after Caesar’s death by the legal establishment of a triumvirate, or committee of three men, who divided the Roman world between them with virtually absolute powers. The rivalry between the most powerful two, Octavian and Marc Antony, persisted for over a decade. The battle of Actium in 31 BC, however, saw the defeat of the combined forces of Antony and his mistress Cleopatra, and left Octavian the undisputed master of the Roman world, a position that he was to maintain until his death in AD 14. The durability of his power was due in no small part to the remarkable constitutional changes he initiated.

After Actium, Octavian began the process by which the institutions of the republic could theoretically be confirmed, while he, for all practical purposes, remained in control. He accordingly handed back the extraordinary powers that he had accumulated. In return he received other powers nominally bestowed by the senate and the Roman people, as well as a new title, Augustus. It was the constant preoccupation of Augustus to present himself as princeps, the ‘first citizen’, a magistrate whose office might involve major responsibilities but who remained in the end essentially no different from other magistrates. By holding significant offices concurrently, with special privileges attached to them, he succeeded in controlling political and military affairs throughout the Roman empire for the rest of his life. This change was regretted by some leading families, who resented the surrender of their political power, but most Romans no doubt welcomed the peace and stability that the principate brought with it.

Under the Augustan settlement, the main deliberative and legislative body remained the senate, which by now consisted essentially of about 600 former magistrates of the rank of quaestor or above. The quaestorship, like the other magistracies, was open only to men, in this case men who had reached at least the age of 25, and the position generally involved financial duties. Twenty were elected annually. It might be followed by one of two offices, either that of aedile, concerned mainly with municipal administration, or of tribune, appointed originally to protect the interest of the plebeians. By this period the old political distinctions between the plebeians and high-born patricians had disappeared for practical purposes, and the tribune was concerned chiefly with minor judicial matters. The quaestor could, if he chose, pass directly to the next office in the hierarchy, the praetorship (twelve elected annually) and be generally responsible for the administration of justice. Finally, he could be elected to one of two consulships, the most prestigious office in the state and one that was eagerly sought after. Formally this could happen only after the age of 42, but an ex-consul in his family line enabled a man to aspire to the office at a much earlier age, possibly by 32, and members of the imperial family sooner still.2 The holding of a senior magistracy, possibly the consulship itself, elevated the holder’s family, whether patrician or plebeian, to the rank of the nobilitas. Once he had held the appropriate office, a man could usually expect to serve as senator for life. But there were exceptions. In the early republic the position of censor was established, to maintain the official list of citizens. He could expel from the senate those members whose conduct was deemed wanting on legal or moral grounds. The office had begun to lose much of its prestige by the late republic and its powers were assumed by the emperors.

On the expiry of their term, consuls and praetors would often be granted a province, which by this period generally indicated a territory organized as an administrative unit. In their provinces the ex-magistrates would continue to exercise their authority in the capacity of their previous offices, that is as propraetor or proconsul. In 27 BC Augustus placed his own territories at the disposal of the senate. They for their part granted him control over a single huge ‘province’, involving at its core Gaul, Syria and most of Spain, for a period of ten years, with the possibility of renewal. It was in these ‘imperial’ provinces that the Roman legions, with some minor exceptions, were stationed. Augustus received the power to appoint their governors (legati Augusti) and the individual legionary commanders (legati legionis), and was thus effectively commander-in-chief of the Roman army, a position fortified by the establishment of a central state fund to provide pensions for retired soldiers. The élite of the army were the praetorians, essentially the emperor’s personal guard, stationed in Rome and other parts of Italy, and enjoying special pay and privileges. The acme of the soldier’s career, the ‘triumph’ that followed a major military victory and involved a splendid military parade through Rome, became the prerogative of the imperial family. The victorious commander, who had achieved his success as viceroy of the emperor, had to be satisfied, unless he was a member of the imperial family, with the lesser honour of triumphal insignia. Governors of the remaining ‘public’ provinces (proconsules) were normally chosen by lot. Egypt was in a special position, legally assigned to Augustus but in effect looked upon almost as a quasi-private domain where he ruled as successor to the Ptolemies.

The smooth operation of the Augustan system required a steady supply of administrators, which would in turn depend ultimately on a healthy birth rate. To encourage stable marriages and the procreation of legitimate children among upper-class families, Augustus enacted a body of social legislation. This provided incentives in the form of improved career prospects and other advantages for both men and women willing to assume their responsibilities, and corresponding penalties against those who were not.

From 31 BC to 23 BC Augustus held a continuous consulship. After the latter date he held the office on only two occasions. This change reflects a growing confidence in his position, but also a desire not to block the ambitions of others or to limit the potential pool of administrators of consular rank. Also, to this end, from 5 BC it became usual for consuls to resign office in the course of the year, to allow replacements (‘suffects’). In return for giving up his consulship in 23 BC, Augustus was granted ‘greater authority’ (imperium maius); since it was ‘greater’ than that of other magistrates, this authority prevailed in the public as well as imperial provinces, and did not lapse when he passed within the boundaries of the city of Rome. It was probably in 23 BC also (there is some disagreement on the matter) that he assumed the traditional authority of the plebeian tribunes, the tribunicia potestas. This conferred certain privileges, such as the right to convene the senate and popular assemblies, and to initiate or veto legislation. It would also make more logical the grant of sacrosanctitas, a privilege associated with the tribunes, which had been conferred on him earlier and which had made an attack on his person an act of sacrilege. The symbolic importance of the tribuncian potestas is illustrated by the practice adopted by emperors of dating their reigns from the time of its assumption.

Below the senators, rated on the basis of their financial worth, stood the equestrians, roughly the entrepreneurial middle class, who had before this period generally found themselves excluded from service to the state. The Augustan settlement opened up major opportunities for the equestrians, including the government of certain smaller provinces, with the rank of prefect or procurator (the latter became the usual title during the Claudian period). At the pinnacle of the equestrian career were the four great prefectures of Egypt, the praetorian guard, the annona (corn supply) or the Vigiles (city police).

Nothing better exposes the fiction that the emperors were essentially regular magistrates than the law that dealt with treason (maiestas). The precise nature of this crime, which predates the imperial period, is unclear. In about 100 BC a Lex Appuleia de Maiestate was enacted, apparently to punish the incompetence of those who had mishandled the campaign against the hostile Germanic tribes, the Teutones and Cimbri. The charge seems to have involved negligence rather than criminality. Somewhat later, under the dictator Sulla, a Lex Cornelia de Maiestate was aimed at preventing army commanders from taking their armies out of their provinces. Under Caesar this law was replaced by a Lex Julia de Maiestate. The actual misdemeanours covered by Caesar’s legislation are not clear, nor is the penalty—it may technically have been death, but in practice resulted in a form of exile. Caesar’s law was replaced by a later Lex Julia under Augustus, one that resulted in significant changes. The Augustan law was interpreted to include verbal abuse and slander in its definition of maiestas laesa. It protected the state against ambitious army commanders, and from threats against the security of the state, much as it had done during the republic. But there was now a new element. It protected the emperor against personal attacks, both physical and, more significantly, verbal; lèse majesté as we know the expression. Gradually the penalties became more and more severe, leading to death. The imprecision of the crime and the inducement offered to the original complainant, in the form of a portion of the fine imposed in the case of conviction, inevitably encouraged the proliferation of the semi-professional accuser (delator). Maiestas trials were the most hated feature of the principate, and on accession each Julio-Claudian emperor after Tiberius foreswore at least those cases that involved slander (an undertaking that inevitably proved impossible to sustain). Given the imprecise nature of the crime, it was open to serious abuse, especially since the princeps had the power to conduct proceedings in camera. There was a common belief that influen`tial figures in court, especially the imperial wives, were heavily involved in many of the trials.3

The formal involvement of women in public life was limited essentially to certain priestly offices and, in particular, to membership in the Vestal Virgins. Vesta was the goddess of the hearth, and her state cult was established in the round temple near the Regia in the forum. It housed a sacred fire and the community of Vestals (who numbered six in the Augustan period) were charged with tending it. A Vestal was expected to remain chaste for the duration of her service (normally thirty years), after which she was free to marry (but rarely did). She was removed from the control of her paterfamilias (see below) but came under the authority of the pontifex, who could punish her by scourging for letting out the sacred fire or by death for violation of her chastity. She enjoyed several privileges, such as special seats at the games and sacrosanctity; these special privileges would gradually be acquired also by prominent women of the imperial family.

The only other quasi-political role for an upper-class Roman woman was to strengthen family alliances through marriage. Daughters, even wives, would find themselves used as political tools. As Pomeroy has observed, even the nation’s founding hero Aeneas of Troy, according to tradition, broke off an affair with Queen Dido of Carthage, whom he loved, and planned a dynastic marriage with the daughter (whom he had never met) of the Italian King Latinus. This practice became very common in the late republic. Thus Caesar sought to cultivate Pompey’s adherence by offering him marriage with his daughter Julia. Octavian broke off an earlier engagement to become betrothed to Marc Antony’s daughter, but in turn broke this pact to marry Scribonia, who was connected to Pompey’s renegade son, Sextus Pompeius. He also arranged the marriage of his sister, Octavia, to Marc Antony.

At first sight the Augustan reforms might seem to have no political significance for a woman like Agrippina. As a result of the changes he initiated, a man as humble as a freedman (a liberated slave) could aspire to the governorship of a province, as happened to Felix, the procurator of Judaea, before whom Saint Paul was granted his famous hearing. But such opportunities remained barred to women, no matter how high born or accomplished. All the same, in its own curious way the imperial system did allow a limited group of women certain political advantages. From 27 BC men who held office did so as servants of the emperor. Power, in the sense of the ability to influence ‘policy’, resided in the first instance with the emperor. Beyond this, as in any quasi-monarchical system, it was exercised by those lucky enough to win his ear. Such individuals might be holders of high office, like powerful army commanders, governors of important provinces, prefects of the imperial guard or even able freedmen performing key tasks within the emperor’s chancery. But they might also be personal friends, either foreign or Roman, and they might also be wives. The involvement of the imperial wives in this process caused deep bitterness among contemporary Romans, and this resentment had a serious impact on the way such powerful women are presented by the literary sources. The ill-feeling had its roots in long-held views about the role that women should properly expect to play within the framework of the Roman state.4

By the Augustan age some Roman women had managed to acquire personal wealth and independence undreamt of in Classical Athens and still regularly denied them even in many otherwise progressive states before the twentieth century. The ancient form of Roman marriage, whereby a bride was passed over to the total authority (in manus) of her husband was by this time little more than a historic relic, and from a relatively early period women had acquired the power to inherit, own and bequeath property. Nominally this power was administered under the direction of a man. A daughter remained under the authority of her paterfamilias (usually her father, but possibly her paternal grandfather or even great-grandfather if he was alive). On the death of the paterfamilias, custody over her passed technically to a guardian, normally the closest male relative. The wealth and prominence of a number of women in the late republic show that this apparently draconian control was less irksome in practice than in theory, and could be avoided by a range of devices, such as an appeal to a magistrate. Even the formal and legal restrictions were removed under Augustus from those women who had borne three or four children.

In one particular respect the Romans were relatively enlightened—in their attitude towards the education of young girls. Unlike boys, girls generally did not study outside the home with philosophers or rhetoricians, largely for the simple practical reason that they tended to be married by the time such arrangements would normally come into force. But they did share domestic tutors with their brothers before marriage, and the evidence indicates that in Agrippina’s day husbands encouraged their wives after marriage to continue their intellectual and artistic pursuits. Pliny the Younger, for instance, was pleased to find his young wife reading and memorizing his writing, and setting his verses to music. Cornelia, the wife of Pompey, was well versed in literature, music and geometry, and in the habit of listening to philosophical debates. Caerellia, a friend of Cicero, was interested in philosophy and was so anxious to get a preview of his De Finibus that she used the copyists hired by Cicero’s friend Atticus to get unauthorized access to it.5 One of the most celebrated speakers of the late republic was Hortensia. She belonged to a large group of wealthy women whose male relatives had in 42 BC been proscribed, and who were taxed to provide revenues for the triumvirs. The women congregated in the forum to protest, and Hortensia gave a celebrated speech on their behalf. Almost a century and a half later Quintilian testifies to the eloquence of her oratory and says that her works were still read on their own merits and not just because of the novelty that they were written by a woman.6 The phenomenon of the educated woman is confirmed by the remarks of the misanthropic Juvenal, who declares his horror at females who pontificate on literature, discourse on ethics, quote lines of verse that no-one has heard of and correct your mistakes of grammar.7 Thus when we hear of the younger Agrippina writing her memoirs, and of the emperor Tiberius responding to her mother’s taunts in Greek, presumably expecting to be understood, it should come as no surprise that both mother and daughter had developed sophisticated literary skills.

This enlightened attitude did, to some degree, have an ulterior motive. Quintilian advocates that mothers should be educated so that they might educate their sons in turn.8 In the Dialogus attributed to Tacitus, Vipstanus Messala fondly recalls worthy women of the old republic. For such women the highest praise was that they devoted themselves to their children.9 First in the list of those Tacitus admired (it includes also the mothers...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Stemma I: The Julio-Claudians

- Foreword

- Significant Events and Figures

- 1: Background

- 2: Family

- 3: Daughter

- 4: Sister

- 5: Niece

- 6: Wife

- 7: Mother

- 8: The End

- 9: Sources

- Appendix I: The Year of Agrippina the Younger’s Birth

- Appendix II: The Husbands of Domitia and Lepida

- Appendix III: The Date of Nero’s Birth

- Appendix IV: The Family of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

- Appendix V: Agrippina’s Movements in Late 39

- Appendix VI: The Date of Seneca’s Tutorship

- Appendix VII: The Decline in Agrippina’s Power

- Appendix VIII: The Patronage of Seneca and Burrus in 54–9

- Appendix IX: SC on Gold and Silver Coins of Nero

- Appendix X: The Final Days of Agrippina

- Abbreviations

- Notes and References

- Bibliography