![]()

CHAPTER 1

• • • •

The comparative approach

Bob Brotherton

Objectives

The general objectives of this chapter are to introduce you to the comparative approach to studying the hospitality industry, and provide you with an opportunity to explore some of the basic conceptual issues associated with this approach. Therefore, when you have read this chapter you should be able to:

1 Explain the difference between simply making comparisons and using the comparative approach.

2 Recognize the differences between comparative and other types of study.

3 Identify the features necessary to make valid comparisons.

4 Distinguish between different approaches to, and types of, comparative study.

5 Explain the difference between contextual and generic factors.

6 Explain what is required to establish an appropriate comparative base.

7 Distinguish between transferability and generalizability in comparative studies.

Introduction

As you will see in this chapter, and indeed the book as a whole, the comparative approach is potentially a very ‘broad church’ which can range from studies explicitly designed to compare two or more individuals to cross-national studies comparing an issue across at least two countries. In this sense it is an approach capable of embracing a wide range of possibilities in relation to the scope and specific focus of the study. For example, Nebel’s (1991) study of the attributes associated with successful hotel general managers (see Case 1.1) was designed to make comparisons between individual general managers in order to establish those attributes common to all of them.

Case 1.1

What are the common characteristics of successful hotel general managers?

This was perhaps the key question this study sought to answer. To achieve this Nebel got ten very successful general managers (GMs) of American hotels to participate in his study. In selecting this group of ten he attempted to create a sample of GMs who were all highly experienced and successful, from both large and small hotels, national and international chains, and one independent hotel. By doing this he was hoping to be able to produce results which could be generalized to the wider community of hotel GMs. However, you may wish to question the extent to which this could be achieved, given the fact that the group chosen for the study was numerically small, based solely on American hotels, only contained one independent hotel GM and was comprised of males only.

The approach Nebel took to collecting his data was one that could be described as qualitative in nature, and the techniques he used would normally be described as non-participant observation and field interviewing. So what do these mean? Studies are generally grouped into two different types – quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative studies are designed to gather numerical or statistical data, whereas qualitative studies seek to obtain ‘softer’ data relating to perceptions, feelings, interactions between people etc. Though Nebel did gather some quantitative data on the GMs’ backgrounds, careers etc., what they did, and how frequently etc., his approach was predominantly qualitative in nature. The non-participant observation and field interviewing techniques Nebel used are best illustrated by his own words:

I stayed as a guest at each hotel, joined the GM as he proceeded through his normal work day; observed and recorded his every activity. I attended the meetings he did, listened in on his phone conversations, watched him do paperwork, and lunched with him. I was, in effect, his shadow … I also conducted extensive interviews with each GM … I conducted additional interviews of about one hour each with the GMs’ key division heads … The field research … resulted in over 700 pages of field notes.

One of the issues Nebel attempted to explore in this study was what the personal characteristics of an ‘ideal GM’ may be. As you might imagine this is a very difficult task because such a person is unlikely to exist! However, Nebel did recognize this problem and justified his decision to attempt this as follows:

No one manager will possess equal measures of each characteristic. But, characteristics that can be shown to be important to the effectiveness of hotel managers are important to know. So the process of trying to discern important, personal, success characteristics lends insight to what it takes to be successful in the hotel business.

In this sense Nebel was trying to recognize the influences arising from the personal characteristics of the GM’s and reconcile this with those emanating from the nature of the job and hotel environment. In short, he was focusing attention on both content and context to identify the general and specific factors influencing the success, or otherwise, of the hotel GM.

By contrast, the study conducted by Kara, Kaynak, and Kucukemiroglu (1995) on consumer perceptions of fast food restaurants in three cities in the USA and Canada (see Case 1.2) was one concerned with more aggregate issues, used a questionnaire survey and was undertaken on a much larger scale.

Case 1.2

Marketing strategies for fast food restaurants

This study was interested in exploring consumers’ perceptions and preferences for fast food outlets and how they differ across cultures/countries. The reason for this being that any similarities or differences could have implications for how the same type of fast food restaurants should be promoted and marketed in different countries. The overall aim of the study was ‘to determine whether the same fast food restaurants are perceived similarly/differently across the two countries [the USA and Canada] and whether their positioning can be improved/changed through careful and selective promotion’.

To implement the study Kara, Kaynak and Kucukemiroglu first reviewed the relevant literature and identified nine fast food restaurant brands specializing in different types of fast food; including McDonald’s, Burger King, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Pizza Hut, to compare across the two countries. In addition to this they also identified eleven attributes that could be used as a ‘common’ basis to ask the different sets of people how they perceived these restaurants. Together these two things helped to establish a common basis for comparison across the two countries, as the same types of restaurant and questions were used in both countries. To extend this comparability further the cities/regions chosen to select the samples and the method used to implement the questionnaire were also ‘matched’ in the two countries. The combination of all these aspects acting to create a common and consistent basis to compare the responses of the US and Canadian consumers.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the results obtained from this study showed a number of significant differences between the perceptions and priorities of the American and Canadian consumers. It would not be appropriate to try and detail all of these here but the following examples will give you a flavour. While older (aged forty-six to fifty-five and above fifty-five) American consumers emphasized the importance of cleanliness, nutritional value and quality of taste, the same category of Canadian customers considered nutritional value and seating capacity to be the most important. On the other hand, the two sets of consumers did not differ in terms of the preferred time to consume fast food.

In practical terms the type of results obtained from a comparative study of this kind could be used to identify different segments of the fast food market and different consumer preferences and behaviours associated with these segments. This knowledge could help the company and/or the unit manager to develop more targeted and effective promotional messages. At an international level there would also be important issues raised over the extent to which a particular brand and product/service format could be exactly replicated, without any modifications, across a number of different countries. The key to making sensible decisions in any of these respects would be the identification of similarities and differences, and their implications.

Thus, at one extreme, the comparative approach may be used to explore an issue associated with particular types of individuals and, at the other, one associated with particular types of hospitality operations or activities across differing countries. In short, the scope for comparative study ranges from the individual to the international. In practice most comparative studies are conducted at a level between these two extremes. Studies that compare two or more companies in the same type of business are quite common, as are ones designed to compare one sector of an industry with another, and those concerned with comparing companies operating in different industries. These types of comparative study are often referred to as intra-sectoral, inter-sectoral, and inter-industry respectively. We shall return to these types later in the chapter and explore some examples of each.

The nature of the comparative approach

At a basic level the comparative approach is simply one of making comparisons, something we do constantly in our everyday lives. Indeed, as Swanson (1971:145) succinctly pointed out many years ago: ‘Thinking without comparison is unthinkable. And, in the absence of comparison, so is all … thought.’ Thinking and learning by making comparisons is a very natural and intuitive process for us. We use comparisons extensively in our daily thinking and interactions with people and various objects. However, making comparisons is not necessarily easy or without its pitfalls. Any comparison may be appropriate and valid, or it may not. A comparison made between things that have some similarity to each other is more likely to be appropriate and valid than one trying to compare things that are totally different. Indeed, everyday expressions such as ‘they are as different as apples and pears, or chalk and cheese’ imply that it is very difficult to make useful comparisons between things that do not have any common features or characteristics. Therefore, this provides our first clue to what may be regarded as a useful and valid comparison, and what may not.

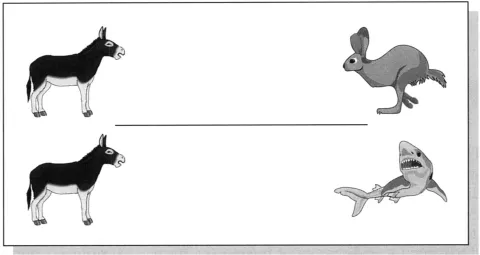

Conceptually we could view this situation as that shown in Figure 1.1. Here we have the two extremes of something being either identical or totally different. Any attempt to make comparisons between things lying at either of these extremes is likely to be a fairly pointless exercise. If two or more things are totally different, in every respect, then there is no basis to make a comparison. Similarly, if two or more things are identical this is all we can say about them. What is more interesting is the intermediate area between these two extremes, within which any things being subjected to comparison will not be either identical or totally different. In short, they will have some features or characteristics which are similar and others which are different.

Figure 1.1 Making comparisons

It is the exploration of these similarities and differences that makes the comparative approach so interesting. This now raises the issue of the extent to which the things are the same or different. For example, we might ask questions such as: is the process of producing food for a hotel restaurant the same as it is in school canteen or a burger restaurant? Are there any differences in the reservation systems used by hotels, airlines, or leisure centres? Do employment practices differ between contract catering and restaurant companies? In seeking to explore questions such as these we begin to adopt a comparative approach to study. However, we must be careful to do this in a meaningful and valid way.

To achieve this it is important that we do not fall into the trap of making surface or superficial comparisons. Things that may initially appear to be either very similar or different on the surface are often seen very differently when a more detailed, and in-depth, analysis is conducted. For example, at first sight a public house and a supermarket may appear to be totally different types of business operation with nothing at all in common. However, a more considered analysis of these two types of business may begin to indicate that they have more similarities than such a superficial analysis would suggest. Both have public and private areas, or a front and back of house, are involved in the retail sale of products to the customer, and regarded as ‘service’ businesses exhibiting direct service staff contact with the customer. In view of this you can see that it may be possible to undertake a valid comparative analysis of some aspects of public house and supermarket operations.

In addition, even where contexts have few, if any, similarities or common features they may still be used to conduct a comparative study where the issue to be studied becomes the ‘constant’ across these contexts. Perhaps one of the best known examples of this is the Peters and Watermans’ (1982) In Search of Excellence study conducted in the USA. Case 1.3 contains a brief overview of this study and illustrates how such a comparative study may be designed and implemented in a valid manner.

Case 1.3

In search of excellence

The aim of this work was to study the most successful companies in America in order to discover why they were so successful and explore the possibilities for transferring their ‘recipes for success’ to other businesses. To study such a wide range of businesses from different sectors of the American economy clearly involved many varied contexts, and raised the question, how could such comparisons be made in a valid way? The first solution to this was to produce a defi...