- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inclusive Educational Practice

About this book

First Published in 2001. An inclusive education is one which seeks to respond to individual differences through an entitlement of all learners to common curricula. (Armstrong and Barton 2000). This book attempts to respond to this definition of inclusion by examining the principles of the literacy curriculum and a range of pedagogic practices. The complex relationships between inclusion, literacy and learning are acknowledged and it is argued that quality learning in language and literacy can work towards increased equity and involvement within the classroom community.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Reading – Shared, Guided and Independent: Principles

The Colour of my Dreams, by Peter Dixon

I’m a really rotten reader the worst in all the class, the sort of rotten reader that makes you want to laugh. | I make these super models, I build these smashing towers that reach up to the ceiling – and take me hours and hours. |

I’m last in all the readin’ tests, my score’s not on the page and when 1 read to teacher she gets in such a rage. | I paint these lovely pictures in thick green drippy paint that gets all on the carpet – and makes the cleaners faint. |

She says I cannot form my words she says I can’t build up and that I don’t know phonics – and don’t know c-a-t from k-u-p. | I build great magic forests weave bushes out of string and paint pink panderellos and birds that really sing. |

They say that I’m dyxlectic (that’s a word they've just found out) but when I get some plasticine I know what that’s about. | I play my world of real believe I play it every day and teachers stand and watch me but don’t know what to say. |

I make these scary monsters, I draw these secret lands and get my hair all sticky and paint on all me hands. | They give me diagnostic tests, they try out reading schemes, but none of them will ever know the colour of my dreams. |

As the poet Peter Dixon suggests, the uniqueness of each child needs to be acknowledged, their talents and interests identified, their reading skills and strategies assessed, and their attitude to reading and range and preferences recorded. In most cases schools do review their planned provision for readers who struggle, but targeting specific support through IEPs should not involve a narrowing of the curriculum, a reduction in the range of opportunities experienced or a diet of impoverished texts. On the contrary, a rich engaging reading curriculum is every child’s entitlement, a prerequisite for developing readers who can and do choose to read independently. It is therefore encouraging that the National Curriculum requirements for reading highlight interest, enthusiasm and independence.

During Key Stage 1, pupils’ interest and pleasure in reading is developed as they learn to read confidently and independently. They focus on words and sentences and how they fit into whole texts. They work out the meaning of straightforward texts and say why they like them or do not like them.

During Key Stage 2, pupils read enthusiastically a range of materials and use their knowledge of words, sentences and texts to understand and respond to the meaning. They increase their ability to read challenging and lengthy texts independently. They reflect on the meaning of texts, analysing and discussing them with others.

(DfEE 1999a)

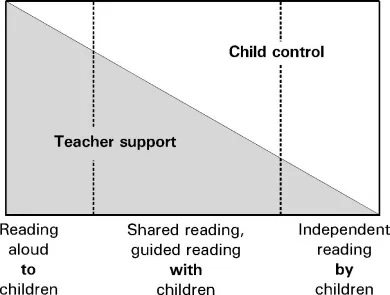

In both these National Curriculum statements, children’s interest and pleasure in reading is appropriately foregrounded, for without such pleasure and enjoyment, children will not develop as readers. Books need to be read to children, with children and by children in order for them to make meaning and develop independence (Clay 1991 a), as the NLSF acknowledges in requiring read aloud time (to), the literacy hour (with) and independent reading time (by themselves) (Figure 10).

Figure 10 The relationship between teacher support and child control (adapted from Norman, K. (1990) Teaching, Talking and Learning in Key Stages 1 and 2. National Association of Teachers of English (NATE) and National Curriculum Council (NCC))

The planned reading curriculum needs to be predicated on interest and motivation since children need to learn what reading can do for them. A rich diet of ‘involved read aloud’, interactive shared reading, supported guided reading discussions and a plethora of independent reading activities must be enthusiastically offered to all readers. The experience of learning to read, and the satisfaction and rewards offered by reading, motivate learners to apply the skills they have been taught and extend their reflective reading, confidence, competence and pleasure. However there are challenges.

There is a clear danger that, in some classrooms, the important pleasures and understandings, which gradually evolve through the experience of reading could be lost if the ‘penalty’ for reading together is too much close textual analysis. It takes great skill and sensitivity by teachers to achieve an acceptable balance between the macro-and micro-features of particular texts.

(Furlong 1998)

It also takes great skill to teach the reading strategies and skills in an interactive manner that involves the integration of reading, writing, speaking and listening and ensures that practice is not reduced to discrete tasks that mostly relate to sentence/word level work (Frater 2000). As research into effective literacy teachers has shown, these teachers continually and explicitly make connections for their pupils between text, sentence and word level features (Medwell et cil. 1998). A balance between these features needs to be maintained, while bearing in mind two key concerns in English teaching: the exploration of meaning and the evaluation of quality.

Text, Sentence and Word Level Work

At text level, the focus is on comprehension: response to text. This will involve both the personal responses of readers, and critical reflection on those responses in order to understand why and how the text provoked that response. Children need to examine the text closely to support and justify their response, so that ‘the parts played by both the text and the reader are recognised and given status in the classroom’ (Martin 1999). Understanding the purpose, audience and form of the text will contribute to this comprehension, as will sentence and word level knowledge and a range of reading strategies. If comprehension is viewed as an active, informed and reflective engagement with texts then the involvement of the children and the quality of the text are critical. Comprehension activities are essentially interactive and discursive, since through this interaction the reader uses both themselves (their life experience, personality, thoughts, interests and values), and their developing knowledge of how the text is crafted (and its conventions) to make meaning.

The organisational and structural features of text, content, themes and language, all need to be explored, attended to and understood for children to develop conscious and justified preferences and a deeper understanding of the craft of writing. A range of fiction, poetry and non-fiction must be shared, enjoyed and actively examined. A range of comprehension activities can be employed including, for example, drama, role play, performance, discussion, retelling, re-enactment with puppets, questioning and a variety of written responses. These will draw on the text as a model and illuminate its meanings and its construction. They may also seek to represent it in another genre or use it as a basis for creating an imaginative alternative or parody.

At sentence level, the focus is on the grammatical features and punctuation used and how these contribute to the meaning of the text. Work highlighting these aspects will mostly be embedded in the text itself and will involve the teacher and pupils identifying, discussing and interpreting the specific use of grammar and punctuation in different genres. While much grammatical knowledge will remain unconscious, it is important that readers can call on some explicit knowledge of grammar and punctuation when they meet a difficulty in their comprehension. Rereading to check for sense, reading on to the end of the sentence and so on, are some of the many self-correction strategies that readers need to learn. Active participation and involvement is essential to make reading-writing connections explicit (Corden 2000). Through these activities children can learn more about the linguistic features and this understanding can be transferred to their own writing. In attending closely to a shared text and noticing, say, exclamation marks and discussing how they are used, children can identify these in other texts (particularly their own reading book), and try them out in writing. As with all language skills, however, it is likely that young or inexperienced readers’ appreciation of punctuation will precede production, but with contextualised teaching that encourages discovery, discussion, participation and investigation in shared, guided and independent contexts, their appropriate use of it will grow. Children receive mixed messages from printed matter around them. For example, Oxford Reading Tree uses single quotation marks but many schools teach the use of double quotation marks; ‘sixty-six and ninety-nine’ (Scott 1997). In one book sample, 74 per cent of the children’s texts studied had sentences that ended at the end of a line (Robinson and Hall 1996). Such issues need to be attended to in selecting texts for shared work.

At word level, the focus is on the teaching of phonics; sounds and spelling. Grapho-phonic decoding skills will be taught, practised and applied in shared and guided reading, and in time set aside for this purpose. This involves the explicit teaching of phonic skills, word recognition, graphic knowledge and vocabulary at KS1, and spelling and vocabulary work at KS2. Again, empty mechanical exercises are to be avoided and engaging focused activities are recommended. Some of this work will be drawn out of shared texts, and some will be undertaken separately using investigations, explorations and language play in quick ‘game’ based learning encounters. A high profile structured approach to phonics teaching is articulated in the NLSF, which builds on the work of Adams (1990), who concluded that successful teaching approaches include both systematic code instruction and the reading and writing of meaningful text. The need for grapho-phonic teaching is clear (e.g. Beard 1993; Dombey 1998a) and an inclusive approach is argued for (Bielby 1998; Dombey 1999). This would include onset and rime and chunking (e.g. Goswami and Bryant 1991; Goswami 1999), one-to-one relationships (e.g. Watson and Johnson 1998; McGuiness 1998) and the study of morphemes. A useful conceptual framework for phonics learning is provided by Frith (1985), who argues that there are three stages in children’s progress in reading and spelling:

- the logographic phase – whole word recognition, and more attention to the letters that words are composed of, but not yet associated with the speech sound;

- the alphabetic phase – of onset learn about the alphabet letters and correspondence, awareness and rime, and learning by analogy;

- the orthographic phase – no longer process new words bit by bit, the major spelling patterns are internalised.

Frith (1985)

From this framework explicit whole-to-part phonics instruction has grown, teaching parts of the words after a story has been read to, with and by children, rather than before the story is read (Moustafa 1999). Children must receive balanced phonics instruction and need to be encouraged to see patterns, draw inferences and make inductions and analogies for themselves, so they will be equipped with a systematic but flexible grapho-phonic approach to word identification, which enables them to take an active role in their own learning. As the NLS argues:

Phonics can and should be taught in interesting and active ways that engage young children’s attention, are relevant to their interests and build on their experiences.

NLS (DfEE 1998b)

All word level work should be relevant to learning needs, involve explicit teaching and demonstration, investigation and enquiry, a synthesis of understanding and practice and consolidation. In learning to spell, for example, children need to be encouraged to investigate words, to discover rules and definitions for themselves through problem solving and to accept responsibility for their own learning. In studying words in shared reading, spelling patterns and meanings of word structures become more explicit, and children can develop a stronger word consciousness, which builds on their use of a range of reading and spelling strategies.

The Reading Environment and the Texts

The reading environment and the texts made available to children make a substantive difference to their reading development. However, teachers must not confuse the provision of a wealth of quality texts in a print rich environment with t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Language, literacy and learning in context

- Inclusive Educational Practice – Literacy

- Assessment and target setting

- Speaking and listening

- Reading – shared, guided and independent

- Writing – shared, guided and independent

- ICT, enabling literacy and learning

- Working collaboratively with parents

- Working collaboratively with LSAs

- Finally

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Inclusive Educational Practice by Teresa Grainger,Janet Tod in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.