![]()

Chapter 1

What is linear editing?

Before considering nonlinear editing, it is necessary to define what linear editing is. Linear editing is usually used to describe videotape editing. The term linear editing arrived after the advent of computerized nonlinear editing and, while the designation may well have originated from some sales pitch, it has stuck and is in many ways an appropriate term.

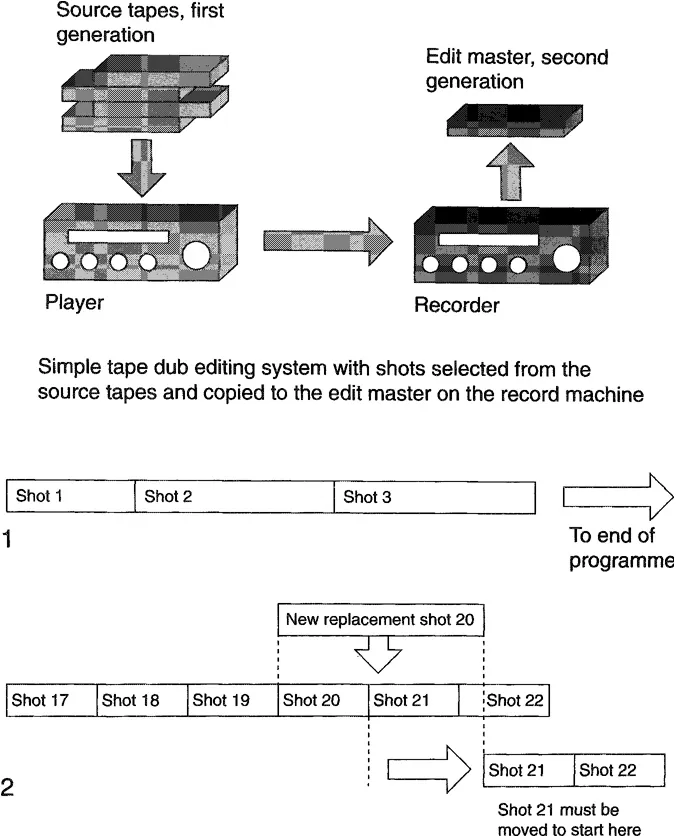

Linear videotape editing is the copy or dub editing process where shots are selected and copied from the source tape to the record or edit tape. The term linear highlights the straight-line principle of editing on tape, where typically an editor will start with shot one of a sequence and then add shot two, then shot three and so on until the programme is complete. What must be remembered is that tape-to-tape editing is a real-time process, which means that a 10-second shot will take 10 seconds to copy from the source tape to the record tape. In fact the actual process is longer than real time when one adds pre- and post-roll times.

This in itself is fine, but problems start to arise when changes are made. For example, suppose there is a 50 shot sequence and the decision is made to replace shot 20 with a new longer shot, but at the same time shots 21 to the end of the sequence are to remain the same length.

There are solutions, but the two most common do impose penalties. One approach is to take the whole programme down a generation and at the appropriate point add in the new material, then continue with the rest of the programme. In effect the original programme becomes a source tape, known as a sub-master. This process unfortunately takes time and results in loss of quality especially when using analogue tape – although with digital tape multi-generation losses are not so much of a problem. The second solution is to add in the new shot at the appropriate point on the original record tape and then re-edit all subsequent shots to complete the programme. This process preserves quality but imposes a major time penalty.

The limitations of tape

(l) Shots edited in a straight-line process.

(2) Making changes to a videotape edit can be time consuming and impose quality penalties.

What’s good?

• For just a few shots, tape-to-tape ‘cuts’ only editing can be very quick.

What’s bad?

• As editing requirements go beyond cuts only, tape-to-tape editing can get expensive.

• If you change your mind then time and quality penalties will beimposed.

Using sub-masters

Using sub-masters saves time, but in an analogue environment can lead to picture degradation.

What is nonlinear editing?

In some ways nonlinear editing is similar to linear editing. The common area is that source material (rushes) must be copied from tape to a new recording medium. The difference is that the new recording medium is a hard disk drive. During this process the off-tape video is converted to a digital format and recorded onto a hard disk drive. In effect the video is edited to the hard disk drive. The hard disk drives are usually external to the computer platform with sizes ranging from 2 GB to 23 GB. It is possible to daisy-chain a number of drives together to increase storage capacity. We shall see later that it is these hard drives that are one of the major limitations of nonlinear systems because you cannot have unlimited storage. This means nonlinear systems are not usually suitable for archive purposes. Wherever possible a programme will be loaded in, edited, downloaded for transmission and then the digitized programme material removed from the hard disk drives.

From here all similarities cease to exist. With all the rushes on the hard disk drives, an editor working on a nonlinear system enjoys the same increased flexibility that a typist does when changing from a typewriter to a computerized word processor. Just as one can copy and paste, duplicate, and move text around in a word processor, so one can manoeuvre sound and vision in a nonlinear editing system.

This cut and paste environment offers tremendous flexibility and speed. At the click of a button a shot can be replaced, lengthened or shortened at any time. Another advantage that these hard disk-based editing systems offer is access to multiple audio and video tracks and sophisticated editing tools. Editors transferring to this new technology may initially be apprehensive but invariably reach a point where they never want to see tape again.

When comparing linear and nonlinear, cost is also a factor. A typical linear videotape edit suite capable of performing simple effects, in addition to basic cuts, requires at least three videotape machines (i.e. two playback machines and a recorder). The installation also needs vision and sound mixing desks and an edit controller. The nonlinear system requires only one player/recorder and the editing system (usually a desktop computer). Overall the nonlinear system is cheaper to both purchase and run.

A basic nonlinear editing system

Usually the installation will include two computer monitors, audio monitoring and sound mixing and a video monitor.

What’s good?

• it is fast and flexible.

• It involves lower cost.

What’s hart?

• There is a new and sometimes steep learning curve.

• Storage is a limitation and needs to be carefully managed.

A nonlinear editing system

Professional systems offer two computer monitors – screen real estate is often at a premium. For quick access to all source material a dedicated monitor is recommended as a resource monitor. The video monitor provides real-time monitoring for quality control. In addition, video waveform monitors and vectorscopes will be installed

![]()

Chapter 2

Editing is primarily about telling a story, using pictures and sound to entertain, inform or educate. But if the quality, that is technical quality, is sub-standard the story may never get told. It could be that a broadcaster will not transmit a programme due to illegal colours being produced, or a client might object to distortion on audio. Whatever the reason, video editors need to have an understanding of the television system and the engineering criteria that apply to video and audio.

The interlaced scanning system

Video images are generated using an interlaced scanning system. An image is scanned from left to right and from top to bottom. Each complete scan from top to bottom is known as a field, which is designated as field 1 or field 2. The combining or interlace of two fields creates a frame. For the UK and most of Europe, the PAL system (Phase Alternating Line) has 312½ lines in each field and as a frame consists of two fields it is therefore made up of 625 scanning lines. The American NTSC system (National Television Standards Committee) uses 262½ lines per field and two fields per frame giving a total of 525 lines per frame. For the PAL system there are 25 frames per second and for NTSC there are 30 frames per second. In fact the NTSC system has a defined frame rate of 29.97 frames per second (see the discussion on timecode in Chapter 5 for more details). There is also the French system called SECAM (Sequential Couleur a Memoire), which uses 625 scanning Sines with a repetition rate of 25 frames per second.

The television scanning

Two-fie!d interlaced scanning. For PAL there are 312% lines per field, 625 line per frame. The field repetition rate is 50 fields per second, and the frame rate is therefore 25 per second. For NTSC there are 262J4 lines per field, 525 lines per frame. The field repetition rate is 60 fields per second and the frame rate is therefore 30 frames per second.

In the analogue world the signals generated are further defined to exist within certain parameters. Ignoring these parameters can lead to a loss of picture quality, which cannot be recovered.

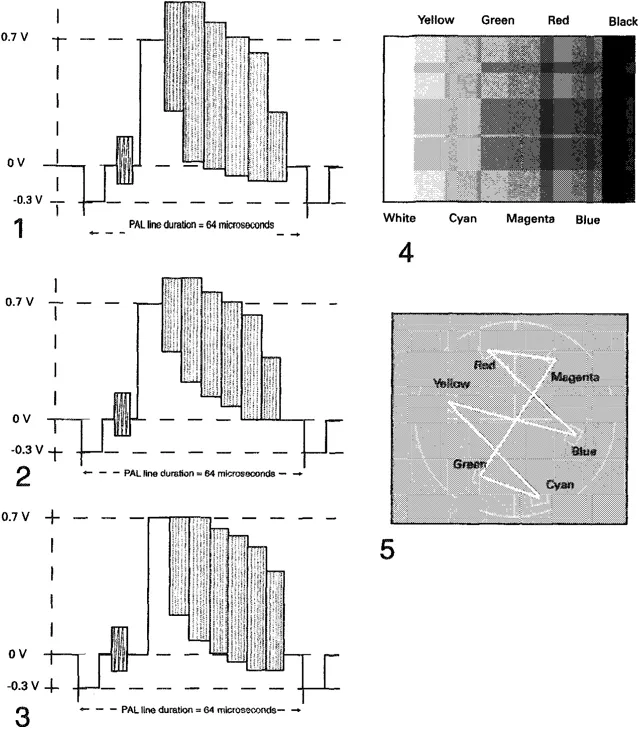

The waveform monitor

A waveform monitor measures the brightness, or luminance, of the video signal. This device is used to confirm that illegal levels of luminance are not being generated, which is an important issue whether recording to tape or hard disks. The parameters of the PAL system define a 1 V signal with peak white at a maximum level of 0.7 V, colour black at 0 V and sync bottom at -0.3 V. While the scales and graticules vary from manufacturer to manufacturer, the essential criterion is that the maximum excursion of peak white should be no greater than 0.7 V from black level.

The vectorscope

The vectorscope is another electronic window into what is happening with the video signal. Its primary function is to measure levels of the colour, or chrominance, part of the signal. The most common signal to use as a reference is colour bars and there are a number of internationally agreed standards for a range of colour bar test signals. For PAL there are three: 100% bars, 95% bars and 75% bars. There should be one set of colour bars at the beginning of each tape, usually 75% or 100% bars. When viewed with a vectorscope the colour bars should conform to defined levels for hue and saturation, where hue is the colour and saturation is the depth of colour. For both PAL and NTSC there are prescribed safe colours and defined maxima for the saturation. A vectorscope is very important to check that the above parameters are not exceeded otherwise the reproduced colour in a domestic TV will not match that at the point of origination.

Colour bar waveforms

(1) 100.0.100.0 colour bars more commonly known as 100% bars.

(2) 100.0.100.25 colour bars more commonly known as 95% bars. (3) 100.0.75.0 colour bars more commonly known as 75% bars.

(4) Colour order as seen onscreen. Note: 100% and 75% bars are the two most common line-up signals found in post-production. Many colour bar types exist but they will normally offer a similar set of line-up reference points. (5) Colour bars as viewed on a vectorscope.

The video monitor

The TV monitor provides a representation of what the viewer will actually see. It is a quality indicator of both source material and completed programmes. The video monitors in any edit suite should be the best that can be afforded as, if the monitor is old or poorly lined up, it can give a misleading and inaccurate reproduction of the image. Some editors have been known to apply colour correction to overcome perceived problems on the...