![]()

PART I

TECHNOLOGY’S RITUALS

![]()

STILL SPEED

with Elizabeth Dungan

Dungan: We work with being, but nonbeing is what we use,” said Lao Tzu. Considering your move to the digital format, how might The Fourth Dimension relate to nonbeing, or emptiness?

Trinh: It’s great to open with Lao Tzu. Although that statement can be addressed in many ways in relation to my work, the fact that you relate it to the digital format and to The Fourth Dimension gives us a more specific direction.

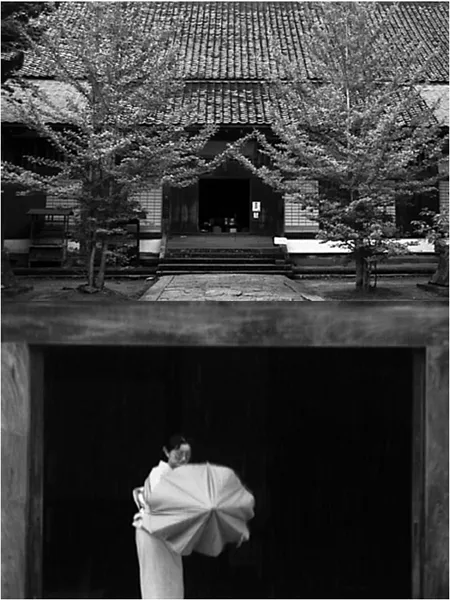

The classic example for this I and not-I relation is that of a splendid cart whose wheels are made with a hundred spokes, and whose truth raises questions among Tao and Zen practitioners as follows: if one takes off both front and rear parts and remove the axle, then what will this grand cart be? The same question underlies the making of The Fourth Dimension, whose subject is not exactly Japan or Japanese culture, but the Image of Japan as mediated by the experience of “dilating and sculpting time” with a digital machine vision. What characterized the digital image is its inherent mutability—the constant movement of appearing and vanishing that underlies its formation. In today’s electronic space of computerized realities, the sage’s words would fare quite well, for one can hear in them all at once: the practical voice of ancient wisdom, the dissenting voice of postcoloniality, and the visionary voice of technology.

Paradoxically, being is not being, and nonbeing is not a negation of being. The spokes’ use for the cart is there where they are not. My work can be said to lie as much at the junction of form and content, as of form and no form. What are intensely present on screen are there actually to address specific absences. Bringing into visibility the invisible would only gain in scope and in dimension if, for example, the film takes as part of its subject of inquiry the invisible forces and relations at work in the creative process. The challenge is to find a way to let the film perform the holes, the gaps, and the specific absences by which it takes shape. Sound and silence, movement and stillness are also not opposed to one another. Silence can speak volumes, especially when it is both individual and collective. Sometimes in speech one clearly hears silence and sometimes what one says is a form of silence. Just as awareness in non-action is the texture that defines a sage’s every action, the musical quality of an instrument and its ability to resonate largely depend upon its internal emptiness.

In the visualizing of Japan, the non-Japan is constantly activated. As it is said, presence gives each event its values, but absence makes it work. For me, realizing a film in the highly advanced technological and economical context of Japan is, in a way, to move ahead into the age of digital compositing so as to return anew to the initiatory power of “pathmaking.” (A term, as stated in the film, used in reference to the name of a Korean refugee who initially introduced the art of gardens in Japan as we know it today. The outside- or the non-Japan is here defining the inside-Japan—what we identify as characteristically Japanese). Such power can be found, for example, in the many existential arts of Japanese culture: the craft of framing time, the skill of behavior, the rites of daily activities, the way of land and water, the calligraphy of visual and architectural environment, or else the time performances of social and theatrical life.

Images of the real, produced at the speed of light, are made to play with their own reality as images. There, where new technology and ancient Asian wisdom can meet in all “artificiality” is where what is viewed as the objective reality underneath the uncertain world of appearance proves to be no more no less than a reality effect—or better, a being time. With digital systems taking part in our everyday thought and work, and with the advent of virtual reality, we are witnessing a profound reality shift, one that radically impacts upon the foundations of our knowledge, and upon our perception of the world.

D: Your response, and your attentiveness to presence and absence, seems to resonate with the very process of digitalization: a translation into a series of zeros and ones, or “on and off.” The underlying foundation of 01010101 relates to these productive couplings of being and nonbeing, absence and presence. In fact, with the digital medium, one can never isolate a “still” image: the image seen on screen is always “in the making” or always incomplete—partially present and partially absent. You’ve written elsewhere about the cinema’s limits. How might The Fourth Dimension transcend, resist, or revise these limits? Can you describe, for example, the role of color in your digital work?

T: I’ve spoken at length on the limits of established categories in cinema. These categories—narrative, documentary, experimental—define the way a film is made and received, and hence its limits. Rather than coming back to these, I will expand a bit on the limits of the visual, the verbal and the musical that constitute cinema’s fabric. Although these three realms are tightly related in my films and are created with similar principles and concerns, they also remain independent in their processes. In deciding “what cinema is all about,” any tendency to favor one of these realms over the other and to establish a relation of domination in which ear, mouth or hand is subordinated to eye, for example, would precipitate one’s encounter with the medium’s limits—if one works intimately with it. The question then is not so much to transcend as to discern them, so as to work with each of them independently and interactively. And the challenge is to operate right at the edge of what is and what no longer is “cinema.”

Cinema is commonly thought of as being essentially visual. As it is practiced in the film industry and in the experimental arena, digital cinema tends to reinforce such a definition, even though the two milieux may differ radically in their eye-dominant treatment of film. On the one hand, you have the story-image—an image re-produced so as to advance the plot or to illustrate the story most efficaciously—and on the other, you have the painting-image—an image activated in its plastic form, or de-formed and made unrecognizable so as to claim its status as pure vision. Steeped in photographic realism and representation, the former has been referred to as being “anti-visual” by those who abide by the latter but, as I’ve discussed elsewhere, I find more relevant the difference made between working in the visual mode, for which legibility is central, and in the image mode, for which alterity is the defining factor. In other words, one may look at images with eyes wide open and yet not see the image and its nature.

Today, altering, dis-figuring, animating, morphing and trans-shaping the familiar in the image has become most popular, thanks to computer technology. Digital production and postproduction have opened doors at many levels in filmmaking, but the one I will briefly mention here is that of special effects. There’s much talk about digital media restoring to us what has been repressed in cinema: visual techniques relegated to the realm of animation and of special effects. Shooting live-action footage is now just a small step in the process. The recorded image has been used primarily as raw material for further compositing. Reality has become “elastic.” The digital format, which is much more capacious and compressible, hence more flexible and versatile than analog, is not only offering a bridge between film and video; it is also displacing fixed boundaries set up between film and animation or computer games, for example. If today’s Hollywood blockbusters are driven by special effects, digital experimental wizardry is obsessed with effects that appeal first and foremost to the retina.

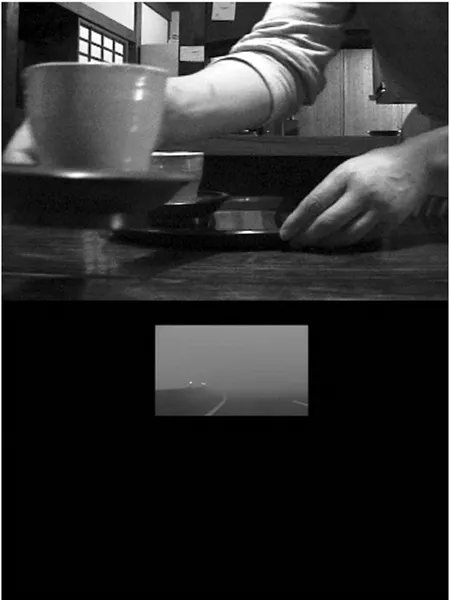

The Fourth Dimension departs from such popularized expectation because its approach to new technology neither indulges in the virtuosity of special retinal effects nor does it rely on distorting, fracturing, or transfiguring images in order to defamiliarize the subject it is engaged with. On the contrary, what partly constitutes the unseen dimension underlying the images offered of Japan is the mutability of relations between the ordinary, the extraordinary and the infraordinary as captured in the mutability of the digital image itself. To call attention to the creative process in the instance of consumption, I did something very simple: I added layers—layers often made visible as they come at precise moments, in selected shapes and colors on top of the image. Working intensely with what I used to hate in video—the unavoidable moiré and iris effects that are exacerbated by video light, and a tabooed color such as bright red, in relation to green—I also emphasize the lightness and portability of the camera in the shooting phase. (The movement of a camera carried on the shoulder is very different from that of a camera held in the palm of one’s hand.) Images are thus shown in their shifting light and traveling motion as well as in their temporal sequencing and mobile framing.

Viewers have commented on the way the screen is turned into a canvas in The Fourth Dimension. As one said, “I like the hand-held shifts. You are painting and veiling with lights as you move.” Although I think that digital compositing has presented us with a host of capabilities in working with the painterly image, I am not at all working under the specter of painting, as a number of experimental filmmakers tend to do. Rather than using digital technology to reinforce the domination of the visual and the retina in cinema, one can certainly use it to propel image making into other realms of the senses and of awareness. Compositing in multiple layers is one of the features in digital editing, whose inventive potential is most appealing, not merely in the crafting of images, but even more so in the designing of sound. This is the one process I truly enjoy while working on the film. The possibilities are indefinite. While I was trained as a music composer, I prefer to work with the local people’s music for the sound track, to which I add improvised music realized by Greg Goodman, who played the prepared piano and a range of other musical objects; and by Shoko Hikage, who performed both the Japanese vocals and the bass Koto. To work with their music not as finished pieces, but as “unedited” sounds the way I work with unedited footage in the montage process—dismantling, splitting, inserting, layering, spacing, joining, trimming and repeating—is a way of continuing their improvisation work in old and new rhythms. This is exciting and very demanding because improvisation requires that we become first and foremost “listeners” in our creations (as differentiated from “sound makers” for example). New technology has made working with audio tracks so much easier. It has given me a lot of freedom in designing sound.

Further, my films are conceived musically—as light, rhythm and voice. I’ve spoken at length elsewhere on the determining role that rhythm plays in social, ethical and political relations. In The Fourth Dimension, I can say, for example, that the two main “characters” and the two most powerful rhythms that I’ve experienced during my stay in Japan are: the train, as it regulates time (the time of traveling and of viewing); and the drum, as it is the beat of (our) life (significantly played by women in the film). The role of music, especially the one performed for the film, is not merely to underscore the action or the visual, but to create a multifunctional space in which many relations between seen and heard are possible. Rather than producing linear, homogenized time, digital sound designing allows me to work intensely with other speeds, those that come not only with the diverse motions in an image, but also with stillness, or with an image emptied of visible action.

D: You’ve described before the ways that artists in ancient China might focus equally on mountains, persimmons, or horses, highlighting the ways in which none of these are static. Nature is always in the course of things. In contrast, representation, by its own “nature,” is an arrested moment, but the quality it represents is always in flux. Can you expand on these insights?

T: Very nice link. For me, filmmaking is really working with relations in the play of senses—among the ear, eye, and hand; the present and the absent, the different elements of cinema; among filmmaker, filmed subject and film viewer; as well as among components of the cinematic apparatus. Relationships are not simply given. They are constantly in formation—undone and redone as in a net whose links are indefinite. And working on relationships is working with rhythm—the rhythms, for example, that determine people’s daily interactions; the dynamics between sound and silence; or the way an image, a voice, a music relates to one another and acts upon the viewer’s reception of the film. Rhythm is a way of marking and framing relationships. Through music, we learn to listen to our own biorhythms; to the language of a people, the richness of silence; and hence to the vast rhythm of life.

This is how I see the link with the tradition of Asian arts, which you evoke in your question. In working with other speeds, the singular and the plural meet on the canvas of time. Artists of ancient China decided, for example, to devote themselves single-mindedly to only bamboo, bird, tree, persimmon or orchid painting during their entire lifetimes. This is not a question of “expertise” as we know it today. If they paint mountains all their lives, it’s not because they want to become an expert in mountains. Rather, I would say, it’s because they receive the world through mountains. Even if one comes to exactly the same place and looks from the same point of view everyday, the mountain is never the same. It would change every single second. In other words, there is no such thing as “dead nature” or what in the tradition of Western arts is considered a still life.

There is no concept of nature morte in ancient Eastern Art. Nature is alive, always shifting. It should be shown in its course. So you can draw thousands of mountains and you can devote your life to painting this single subject, yet each painting shows a unique mountain-instance. Painting here is inscribing the ever-changing processes of nature—that are also one’s own. Painter and painted are, in a way, both caught on canvas in the act of painting. To paint nature is to paint one’s self-portrait. (Although the tradition of Western arts tends to be anthropocentric, Francis Bacon’s self-portraits can be said to be similar in spirit). So this is one way of taking in the world: being so intimately in touch with oneself that every time one returns deep inside, one opens wide to the outside world.

The other approach, which my work may seem at first to exemplify, is to work with multiplicity in an outward traveling mode. But such a distinction is temporary, because ultimately, the two approaches do meet and merge as in my case. I travel from one culture to another—Senegalese, West African, Vietnamese, Chinese and Japanese—in making my films. This may fit well with today’s transnational economy, in which the crossing of geophysical boundaries is of wide occurrence, whether by choice or by political circumstances. But for the notion of the transversal and the transcultural to take on a life in one’s work, traveling would have to happen also in one place, or inward. One can evoke here the depth of time, a notion that is particularly relevant to digital reality. Home and abroad are not opposites when traveling is not set against dwelling and staying home. In a creative context, coming and going can happen in the same move, and traveling is where I am. Where you are is where your identity is; that’s your place, your home and your being now.

D: Constructions of time, and re-imaginings of time, seem to be an important aspect of your work. How might traveling conjure this notion of time and relate it to space? I am also thinking here of one of Paul Virilio’s books entitled The Lost Dimension. Among other things, this book explores an accelerated perspective, a discussion of vanishing points, a sense of displacement, the doubling of space and time. For these and other reasons, Virilio’s work seems very resonant with your own. Given this rhyming of titles between The Fourth Dimension and The Lost Dimension, how might you describe your work in relationship to Virilio’s work?

T: Although I’ve not thought of Virilio in choosing the title—which refers primarily to the dimension of time, of light and of “non-being”—your association is very relevant and refreshing, especially in view of the more common tendency to associate my films with Chris Marker’s films, and this one in particular with Sans Soleil.

I’ve expanded earlier on how, in weaving this mutable light tapestry that is film, I work with uneven and heterogeneous speeds, rather than with a homogenized space of linear time. This can be related to Virilio’s d...