![]()

Chapter | one

Properties of Gases

Chapter 1 is based on an original draft prepared by Mr E.W. Berry

INTRODUCTION

This first volume of the manual deals with the elementary science or ‘technology’ which forms the foundation of all gas service work. It outlines the principles involved and explains how they work in actual practice.

To do this it has to use scientific terms to describe the principles of things like ‘force’, ‘pressure’, ‘energy’, ‘heat’ and ‘combustion’. Do not be put off by these words – they are simply part of the language of the technology which you have to learn. Every activity from sport to music has its own special words and gas service is no exception. While the football fan talks of ‘strikers’, ‘sweepers’ and ‘back fours’ the gas service man deals with ‘calorific values’, ‘standing pressures’ and ‘secondary aeration’.

It is necessary for him to know about these things so that he can be sure that he has adjusted appliances correctly. He must also know what actions to take to avoid danger to himself or customers or damage to customers’ property.

GAS: WHAT IT IS?

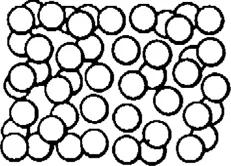

Every substance is made up of tiny particles called ‘molecules’ (see Chapter 2). In solid substances like wood or metal, there is very little space between the molecules and they cannot move about (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Molecules in a solid.

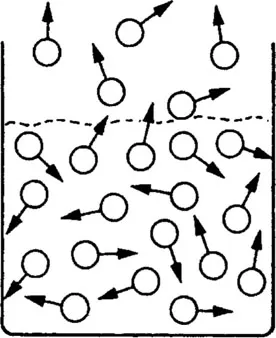

In liquids, there is a little more space between the particles, so that a liquid always moves to fit the shape of its container. The molecules cannot get very far without bumping into each other, however, so they do not move very quickly and only a few get up enough speed to break out of the surface and form a vapour above the liquid (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Molecules in a liquid.

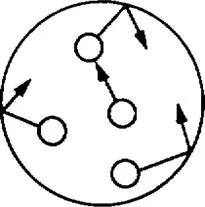

A gas has a lot more space between its molecules. So they are able to move about much more freely and quickly. They are continually colliding with each other and bouncing on to the sides of their container. It is this bombardment that creates the ‘pressure’ inside a pipe (Fig. 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Molecules in a gas.

Because the molecules are as likely to move in one direction as in any other, the pressure on all of the walls of their container will be the same. Gases must, therefore, be kept in completely sealed containers otherwise the particles would fly out and mix, or ‘diffuse’, into the atmosphere (see section on Diffusion).

The word ‘gas’ is derived from a Greek word meaning ‘chaos’. This is a good name for it, since the particles are indeed in a state of chaos, whizzing about, colliding and rebounding with a great amount of energy.

KINETIC THEORY

‘Kinetic’ means movement or motion, so kinetic energy is energy possessed by anything that is moving. A car has kinetic energy when it is moving along a road. The effect of this can clearly be seen if it collides with another object! Similarly gas molecules are in motion and possess kinetic energy at all normal temperatures. The amount of energy increases as the temperature increases. The Kinetic Theory states that:

1. The distance between the molecules of a gas is very great compared with their size (about 400 times as great).

2. The molecules are in continuous motion at all temperatures above absolute zero, −273 °C (see Chapter 5).

3. Although the molecules have an attraction for each other and tend to hold together, in gases at low pressures the attraction is negligible compared with their kinetic energy.

4. The amount of energy possessed by the molecules depends on their temperature and is proportional to the absolute temperature (see Chapters 5 and 8).

5. The pressure exerted by a gas on the walls of the vessel containing it is due to the perpetual bombardment by the molecules and is equal at all points.

DIFFUSION

If a small amount of gas is allowed to leak into the corner of an average-sized room, the smell can be detected in all parts of the room after a few seconds. This shows that the molecules of gas are in rapid motion and because of this, gases mix or ‘diffuse’ into each other.

Graham’s Law of Diffusion

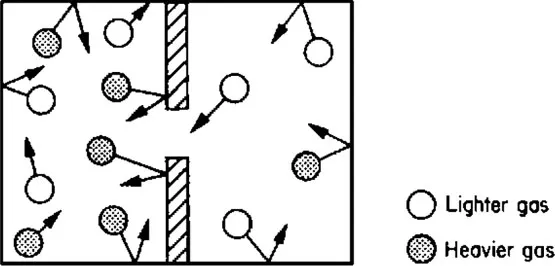

If two different gases at the same pressure were put into a container separated by a wall down the centre and a small hole made in the wall as shown in Fig. 1.4 then, because the molecules are in continuous motion, some molecules of each gas would pass through the hole into the gas on the other side. The faster and lighter molecules would pass more quickly through the hole into the other gas.

Figure 1.4 Diffusion of two gases.

After studying the rates at which gases diffuse into each other, Graham discovered that the rates of diffusion varied inversely as the square root of the densities of gases. Or,

Thus a light gas will diffuse twice as quickly as a gas of four times its density (see section on Specific Gravity).

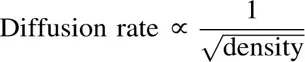

The effect can be demonstrated experimentally by filling a porous pot, made from unglazed porcelain, fitted with a pressure gauge, with a dense gas such as carbon dioxide. Then place it in another vessel and fill that with a lighter gas such as hydrogen (see Fig. 1.5). The pressure inside the inner pot will be seen to rise, proving that the lighter gas is getting into the pot faster than the heavier gas that is getting out.

Figure 1.5 Experiment to demonstrate the effect of diffusion.

CHEMICAL SYMBOLS

Symbols are often the initial letters of the name of the substance, like H for hydrogen, O for oxygen. These symbols are not only a form of shorthand and save a lot of writing, they also show the amount of the substance being considered.

Each single symbol indicates one ‘atom’, which is the smallest chemical particle of the substance (see Chapter 2). So H indicates one atom of hydrogen, O is one atom of oxygen and so on.

It has previously been said that substances are made up of tiny particles called ‘molecules’. This is true, but the molecules themselves consist of atoms. Sometimes a molecule of a substance contains only one single atom, like carbon, which is denoted by C. Often the molecules have more than one atom, like those of hydrogen and oxygen which both have two atoms. So while an atom is indicated by H, the smallest physical particle of hydrogen gas which can exist is shown by H2. The ‘2’ in the subscript position indicates that the molecule of hydrogen is made up of two atoms.

Some substances are made up of combinations of different kinds of atoms. Water is an example. Water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen and its formation is described in Chapter 2. The chemical formula for water is H2O. This shows that a molecule of water has two atoms of hydrogen and one of oxygen combined together. Similarly, methane gas, which forms the main part of natural gas, is made up of one atoms of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen. So its formula is CH4.

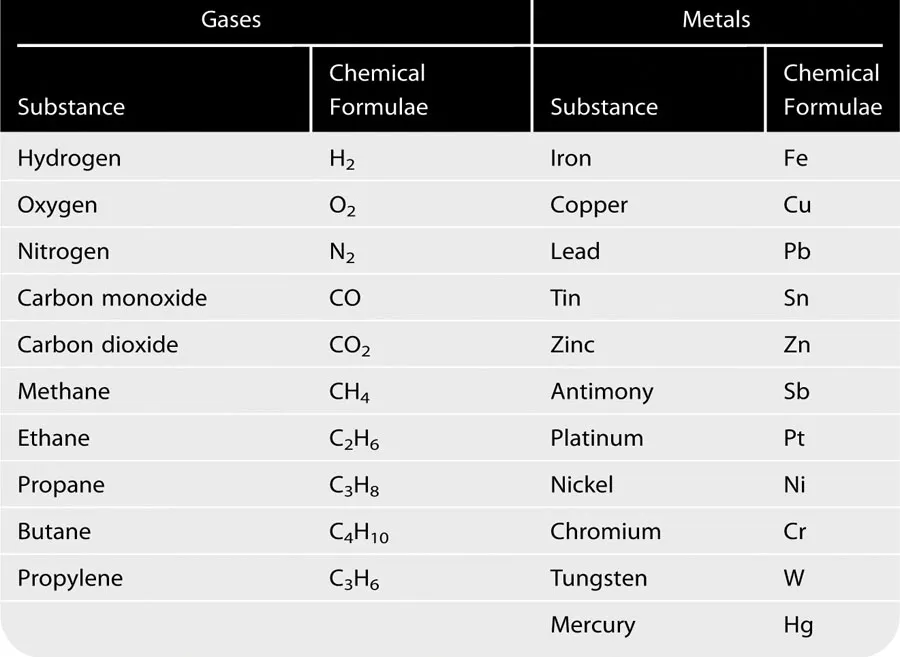

Table 1.1 shows the chemical symbols and formulae for some of the substances met with in gas service work.

Table 1.1 Chemical Symbols and Formulae for Substances Commonly Used During Gas Service Work

ODOUR

Gas can, of course, be dangerous. It can burn and it can explode. Some gases are ‘toxic’ or poisonous. But all fuels are potential killers if not treated properly. Coke and oil both burn and can produce poisonous fumes. Electricity causes more domestic fires than any other fuel and the first indication you get of its presence could be your last!

Gas has the advantage of having a characteristic smell or ‘odour’ so it is easily recognisable. Several of the combustible gases, including hydrogen, carbon monoxide and methane, are colourless and odourless and could not easily be detected without elaborate equipment. To make it possible for customers to find out when they have a gas escape or have accidentally turned on a tap and not lit the burner, a smell or odour, is added to the gas.

Gas manufactured from coal has its own smell, natural gas does not. But suppliers of natural gas are required to add a smell to it before sending the gas out to the customers. So an ‘odorant’ is used, originally a chemical called tetrahydrothiophene. Only a very small amount is added, something like 1/2 kg to a million cubic feet of gas. Odorants now in use contain diethyl sulphide and e...