- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Transport Terminals and Modal Interchanges

About this book

This is the first book to review a trend in transport systems which has only recently come of age: the multi-modal interchange. Separate modes of transport are being linked through 'joined-up thinking', and transport designers and authorities are only now able to exploit interchange opportunities. This book presents examples of how these new opportunities have been planned and designed, and outlines how transfer and mobility can be improved in the future.

Blow takes the airport as the focal point of true multi-modal passenger terminals and presents the development of these buildings as representing a new experience in travel. The book shows that the success of the experience of transferring from one mode of transport to another depends on the many factors, including congestion in an already overloaded system, and the way that designers and managers have addressed contingency planning. International examples are drawn from areas where mobility is most concentrated and the demands on design are at their highest. The book also addresses important issues of rebuilding and redevelopment, where once separate modes of transport are being linked to each other, and where short-term inconveniences rectify past wrongs in the long term. It is a compendium of architectural and engineering achievement.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

| 1 | Introduction |

This book is the first of its kind to review a trend in transport systems which has been active since the advent of mass travel but has only recently come of age. The author takes the airport as the focal point of most truly multimodal passenger terminals, and the book is therefore complementary to many books about airports and airport terminals, capturing the interest in these buildings as representing a new experience in travel.

Whether that experience is wholly satisfactory is dependent upon the exigencies of weather and congestion in an already overloaded system, as well as the way designers and managers have addressed contingency planning. Ease of transfer between different modes of public transport is a great contribution to mobility which can be made by the transport industries. This is the future to which the book points.

In many ways, the future of the movement of goods or cargo also depends upon modal transfer. The warehousing and distribution industries address the assembly and breakdown of loads between individual consumers, town centres, factories and airport cargo terminals with different degrees of containerisation. Only where passenger and goods systems can converge are they addressed in this book: an innovative idea for using rail stations as distribution points for deliveries to towns is shown in Chapter 4.1.3.

The author recognises the organic nature of modern technologically-derived buildings with a taxonomy, a classification of passenger terminal buildings as if they were bio-forms, with integral structures or linked and contiguous forms.

Examples are culled from Britain and the rest of Europe as well as North America and the Far East, where personal mobility is most concentrated. Other case studies from Australia, for example, illustrate the breadth of opportunity worldwide.

Most cities have evolved separate land-based, air and, in some cases, waterborne transport over the years, and their very separateness may have been their salvation in the face of organisation, responsibility and physical constraints. But now, with transport coming of age, that separation is being replaced by ‘joined-up thinking’ and transport authorities are able to exploit interchange opportunities.

Integration is often only achieved by rebuilding and replacing dis-integrated facilities. Therefore, the book captures potent examples of four-dimensional design and construction, redevelopment projects which inconvenience in the short term but rectify past wrongs in the long term. The ‘grafting on’ of rail systems to airports, rather than vice versa, has been achieved at Heathrow Central Area, Manchester, Schiphol and Lyon, for example.

Airport interchange means not just getting to the airport by public transport. It means ‘choice’ and synergy. A hub airport gives better choice of flights. A real interchange point gives more – it gives choice of modes.

European examples are Paris Charles de Gaulle, Zurich, Vienna, Lyon (both Aeroport St Exupéry and Perrache rail/bus station), Schiphol, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Manchester (both airport and Piccadilly rail station), Birmingham, Heathrow, Gatwick, Stansted, Southampton, Luton, Ashford Station, the Channel Tunnel terminal at Cheriton (rail interchange), St Pancras and Stratford in London, and Enschede and Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

There are several examples in the USA (Chicago, Portland, Atlanta, Washington and San Francisco), but Seoul and Hong Kong are pre-eminent in the Far East and there are interesting ones in Australia, including Perth WA.

Special cases are Circular Quay in Sydney (which combines ships, ferries, rail and bus) and Yokohama in Japan.

Many common and converging standards apply to the three modes of transport operative at the interchanges with which this book is concerned: bus or coach, rail and air transport. Functional requirements and processes particular to each interface in the interchange are reviewed briefly and illustrated.

The book therefore aims to promote modal interchange as an increasingly essential feature of passenger transport terminal buildings.

| 2 | History – landmarks in the twentieth century |

Taking as a starting point the inheritance of the great railway building age of the nineteenth century and the start of reliable bus and tram operations, where did the twentieth century take us?

For the reasons highlighted in the previous chapter, not very far in the direction of ‘joined-up’ transport, apart from the ubiquitous bus serving the less ubiquitous railway station. For several decades, air transport had little effect, but by the time when the number of passengers in the UK, for example, using airports becomes commensurate with every single member of the population arriving or departing from an airport several times a year, that is no longer true.

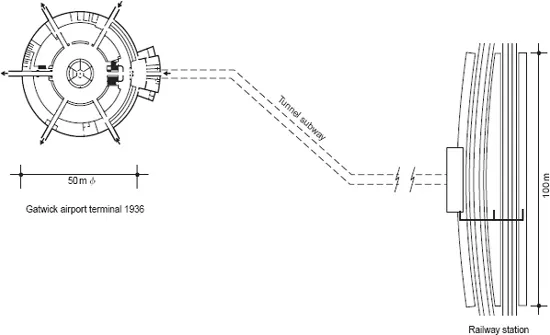

2.1 Gatwick, 1936

The original satellite at London's Gatwick Airport is a generic form of circular building serving parked aircraft. A fascinating story surrounding the design of an airport terminal in 1934 is told in Gatwick – The Evolution of an Airport by John King. It concerns the birth of the idea of a circular terminal building by Morris Jackaman, the developer of the original Gatwick Airport in Sussex.

One problem which particularly concerned Morris was the design of the passenger terminal. He considered that conventional terminal buildings such as Croydon, which had been described as only fit for a fifth rate Balkan state, were inefficient and not suited to expansion of passenger traffic … It is believed that one idea he considered was building the terminal over the adjoining railway. The result of his deliberations was ultimately the circular design which is a feature of the 1936 passenger terminal, now generally known as the Beehive. How this came about is intriguing. Morris was working late one night at his parents’ Slough home when his father came into his study. ‘Oh, for heaven's sake, go to bed,’ his father urged. ‘You're just thinking in circles.’ Instantly Morris reacted. ‘That's it, a circular terminal.’ Morris quickly put his thoughts on the advantages of a circular terminal on to paper. Using the patent agents E. J. Cleveland & Co., a provisional specification was submitted to the Patent Office on 8 October 1934. Entitled ‘Improvement relating to buildings particularly for Airports', the invention sought ‘to provide a building adapted to the particular requirements at airports with an enhanced efficiency in operation at the airport, and in which constructional economies are afforded'.

Various advantages of a circular terminal were detailed. They included:

1 Certain risks to the movement of aircraft at airports would be obviated.

2 More aircraft, and of different sizes, could be positioned near the terminal at a given time.

3 A large frontage for the arrival and departure of aircraft would be obtained without the wastage of space on conventional buildings.

Morris's application went on to describe the terminal as ‘arranged as an island on an aerodrome’ and

The building thus has what may be termed a continuous frontage and the ground appertaining to each side of it may be provided with appliances such as gangways, preferably of the telescopic sort, to extend radially for sheltered access to aircraft. It will be observed that by this arrangement the aircraft can come and go without being substantially impeded by other aircraft which may be parked opposite other sides of the building. This not only ensures efficiency of operations with a minimum delay, but also ensures to some extent at any rate that the aircraft will not, for example, in running up their engines, disturb other aircraft in the rear, or annoy the passengers or personnel thereof. In order to give access to the building without risk of accident or delay of aircraft, the building has its exit and entrance by way of a subway or subways leading from within it to some convenient point outside the perimeter of the ground used by aircraft, leading to a railway station or other surface terminal.

In fact, Morris Jackaman's concept was built at Gatwick to a detailed design by architect Frank Hoar, complete with the telescopic walkways referred to in the patent application and adjacent to and linked by tunnel to the Southern Railway station built adjacent. The first service operated on Sunday 17 May 1936 to Paris: passengers caught the 12.28 train from Victoria, arriving at Gatwick Airport station at 13.10. They mounted the stairs of the footbridge, crossed to the up platform, walked through the short foot tunnel, and completed passport and other formalities in the terminal ready for the 13.30 departure of British Airways’ DH86. They left the terminal through the telescopic canvas-covered passageway to board the aircraft steps. Ninety-five minutes later they reached Paris. The whole journey from Victoria had taken two-and-a-half hours and cost them £4-5s-0d, including first class rail travel from Victoria.

2.1 Gatwick Airport Terminal, 1936.

2.2 Gatwick Airport, the flight boarding (courtesy of John King and Mrs Reeves (née Desoutter)).

2.3 Gatwick Airport, showing the railway station.

REFERENCES

Hoar, H. F. (1936). Procedure and planning for a municipal airport. The Builder, 17 April–8 May.

King, J. (1986). Gatwick – The Evolution of an Airport. Gatwick Airport Ltd/Sussex Industrial Archaeological Society.

King, J. and Tait, G. (1980). Golden Gatwick, 50 Years of Aviation. British Airports Authority/Royal Aeronautical Society.

2.2 Other successful multi-modal

interchanges (see Chapter 6)

interchanges (see Chapter 6)

The four London airports of Heathrow (6.1.4, 6.1.5, 6.3.4), Gatwick (6.2.4), Stansted (6.2.3) and Luton (6.4.1) have all become multi-modal, with differing degrees of success. Others in Britain include Birmingham (6.3.2), Manchester (6.3.3) and Southampton (6.3.5).

The same pattern is repeated throughout the world, except that the greater the car usage, the less railway and bus usage and the fewer multi-modal interchanges.

| 3 | The future development of integrated transport |

Most cities have evolved separate land-based, air and, in some cases, waterborne transport over the years. The very separateness of these transport systems may have been the key to their viability in the face of logistical and physical constraints. Major cities like London and Paris have national rail and coach networks radiating from many stations, and both central and peripheral to their inner hearts. Despite the theoretical opportunities for riverborne transport linking other stations, the more universal solution of underground railway lines has been adopted. Only for waterside cities like Venice and Sydney can ferry systems make a real contribution. New low-density ‘cities’ like Milton Keynes in the UK in the 1960s and national capitals like Canberra and Abuja created in their planning networks of roads, bus-ways, etc., but high-density cities are not by definition planned from scratch.

3.1 Resolution of complexity of transport systems caused by dis-integration

First, we examine particular modes, why they demand inherent complexity, and compare air and rail.

3.1.1 Air

Why should an airport terminal be so complicated and ultimately so expensive? Why should a terminal be designed around the baggage system, and an ever more complicated one at that? Why should baggage handling be so? Because in the early days, air travel was for the rich few who could not take their flunkeys with them – so the airlines and airports doffed their caps and dealt with the cases. Conversely, rail travel, even transcontinental rail travel, was never like that. As far as is known, no airport or airline has attempted the railway system.

The reason lies with the aircraft. Boeing in the mid-1970s announced the 7 × 7, which became the 757 and 767, and one aim was to increase, or allow airlines to increase, the cabin baggage capacity, because that was thought to be a desirable option. The outcome was that ‘bums on seats’ were more important than eliminating a ground-level problem, and so the necessity for security-conscious ground-level baggage handling has escalated to the costly and high-t...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: History - landmarks in the twentieth century

- Chapter 3: The future development of integrated transport

- Chapter 4: Two particular studies point the way

- Chapter 5: Twenty-first-century initiatives

- Chapter 6: Taxonomy of rail, bus/coach and air transport interchanges

- Chapter 7: Common standards and requirements

- Chapter 8: Bus and coach interface

- Chapter 9: Rail interface

- Chapter 10: Airport interface

- Chapter 11: Twenty-first-century trends

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Transport Terminals and Modal Interchanges by Christopher Blow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.