- 238 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Architecture of Schools: The New Learning Environments

About this book

This is the standard design guide on schools architecture, providing vital information on school architecture.

Mark Dudek views school building design as a particularly specialised field encompassing ever changing educational theories, the subtle spatial and psychological requirements of growing children and practical issues that are unique to these types of building.

He explores the functional requirements of individual spaces, such as classrooms, and shows how their incorporation within a single institution area are a defining characteristic of the effective educational environment.

Acoustics, impact damage, the functional differentiation of spaces such as classrooms, music rooms, craft activities and gymnasium, within a single institution are all dealt with. More esoteric factors such as the effects on behaviour of colour, light, surface texture and imagery are considered in addition to the more practical aspects of designing for comfort and health.

Chapter 4 comprises 20 case studies which address those issues important in the creation of modern school settings. They are state of the art examples from all parts of the world. These examples include: Pokstown Down Primary, Bournemouth; Haute Vallee School, Jersey; Heinz-Galinski School, Berlin; Anne Frank School, Papendract, Netherlands; Seabird Island School, British Columbia and The Little Village Academy, Chicago.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Architecture of Schools: The New Learning Environments by Mark Dudek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Origins and significant historical developments

DOI: 10.4324/9780080499291-1

Introduction

The naturalistic settings sought for education at the beginning of the century, seen in early examples such as the open-air, Steiner and Montessori schools, all carried within them themes which run throughout the history of twentieth century school architecture. Initially viewed as an issue relating merely to hygiene and the spiritual well-being of underprivileged children in the newly industrialized cities, the desire to make the experience of education more suitable to young children broadened to encompass other concerns. From the 1920s these included a growing interest in child psychology and a more enlightened approach to the educational needs of large pupil numbers within the expanding cities.

To balance these radical impulses, it can be said that the more privileged private education systems tended to maintain an approach to buildings for education which deliberately set out to make them institutionalizing in their own right. This could be seen particularly in the English public school tradition, where strict hierarchies were reflected by an architecture which changed little within the intervening decades of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. How to de-institutionalize the institution can be seen as a significant topic within the evolving theory of school design elsewhere.

Within this chapter I explore some of the more enduring themes represented by both the radical and the traditional wings, viewed through the most influential buildings and architects. I do not set out to present a detailed account of the history of school architecture. Rather, I describe some of the recurring educational and social concepts which enabled architects to respond in specific and distinctive ways to the needs of children in mass education.

To begin I consider briefly the roots of an architecture for education, not by way of the first dedicated school buildings, but within the framework of an anthropological view of space as defined by Edward T. Hall and his analysis of the house:

People who ‘live in a mess’ or a ‘constant state of confusion’ are those who fail to classify activities and artefacts according to a uniform, consistent or predictable spatial plan. At the opposite end of the scale is the assembly line, a precise organization of objects intimeandspace.1

Hall’s dialectical arguments may quite easily refer to contemporary school design, which has reached a point where rooms and spaces are intended to meet precise functional needs, and the function of school is framed in neat periods of time, dedicated to specific subject areas. If a modern secondary school comprises as many as twenty specific areas for teaching (aside from numerous smaller ancillary areas), although the outcome of education may be predictable, it also suggests that the range of activities is encouraging a broad and interesting form of education, which nevertheless encompasses large measures of control. It is, however, far removed from the mono-functional spaces of the factory floor or, as we will see, the first schools with their provision of large schoolrooms in which hundreds of children could assemble for instruction at one time.

The implication of Hall’s analysis of function relating to the house, where there are special rooms for special functions, does however determine a modernist conception of how people should live their lives. Rooms in the house are allocated specifically to cooking, eating, lounging/entertaining, rest, recuperation/procreation and sanitation. These are functions so precise that they might set the agenda for life. They can impose mental straitjackets. Life is framed by the environments within which it is set; an order is established levelling and stultifying the possibility for wider social interaction, the source from which education springs. Seen in these terms, there is little or no possibility for the form to be interpreted imaginatively. If the school is based upon a similar mono-functional model to the house, it may also have a negative effect on the personal development of the child.

Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger, who has made a significant contribution to the architecture of schools, puts it this way: ‘… a thing exclusively made for one purpose, suppresses the individual because it tells him exactly how it is to be used. If the object provokes a person to determine in what way he wants to use it, it will strengthen his self identity. Merely the act of discovery elicits greater awareness. Therefore a form must be interpretable – in the sense that it must be conditioned to play a changing role.2 This defines the essential dialectic at work within the history of school design during the nineteenth and the early part of the twentieth century: on the one hand, the urge to impose discipline and control through a resolute set of spaces; on the other, the emerging desire to encourage individual creativity by the production of buildings which were not enclosing and confining. Rather they opened themselves up to the surrounding context, its gardens and external areas, which themselves became a fundamental part of the ‘learning environment’. Social interaction, rather than autonomous isolation, became the educational strategy embodied in Hertzberger’s influential school buildings of the 1980s.

As with the school, the house as a functional layout with a deterministic programme, which is now taken for granted, is a relatively recent interpretation. Philippe Aries’ Centuries of Childhood points out that rooms in European houses had no fixed function until the eighteenth century. He asserts that, before this time, people came and went relatively freely within dwelling houses. Beds were set up whenever they were needed. There were no spaces that were specialized or sacred. Certainly there were no rooms or buildings dedicated to the education and development of younger children. The ‘school’, for most children of the middle ages, was the everyday world they inhabited.

Nevertheless, in eighteenth century western societies the home began to take on characteristics of its present form. Rooms were identified as being bedrooms, dining rooms and kitchens, each having their own function. Furthermore, the concept of the corridor came into being. This was a rationalization of the communal meeting place (around the entrance) or hall, which had been the original all-purpose living/sleeping/eating area. The corridor enabled private activities to evolve and the house took on the form of an internal street, with rooms arranged in an orderly form along either side. The children’s playroom or nursery would often double as their sleeping area, enabling children’s games to develop and evolve over extended periods of time.

Often it would be treated as a private territory, a little house in its own right. The room was a secure microcosm of the home itself, with its own social hierarchies played out between brothers, sisters and childhood friends. It would become an important mechanism in the development of social competence, safe from the outside world yet capable of replicating some of its difficulties and complexities. According to Hall, man’s knowledge and control of space, which he describes as being ‘orientated’ is a fundamental characteristic of this social development. Without this sense of control of one’s environment, to be disorientated in space, is the distinction between survival and sanity: ‘To be disorientated in space is to be psychotic’.

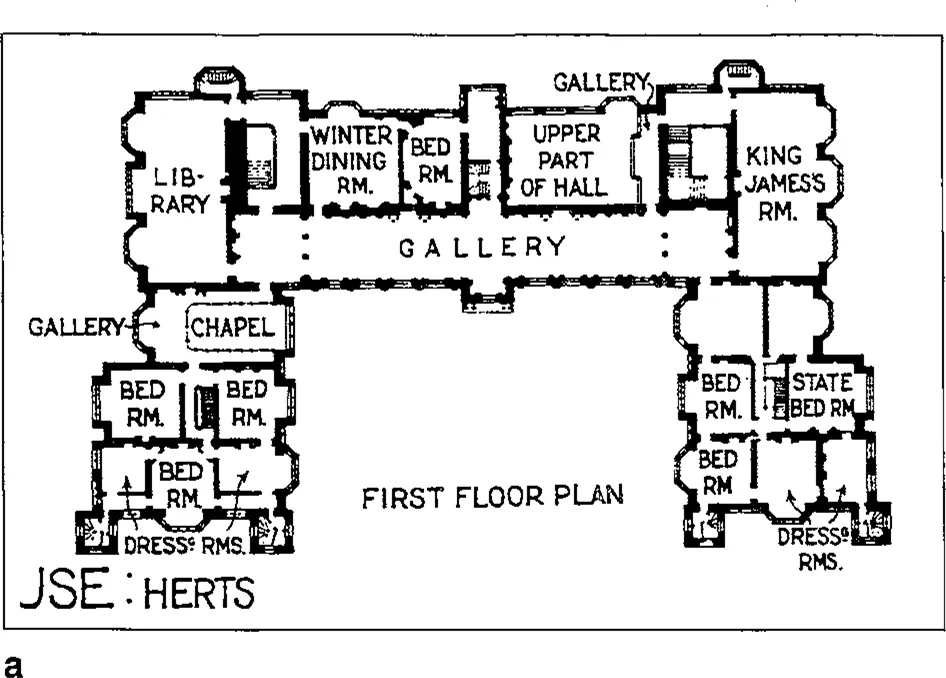

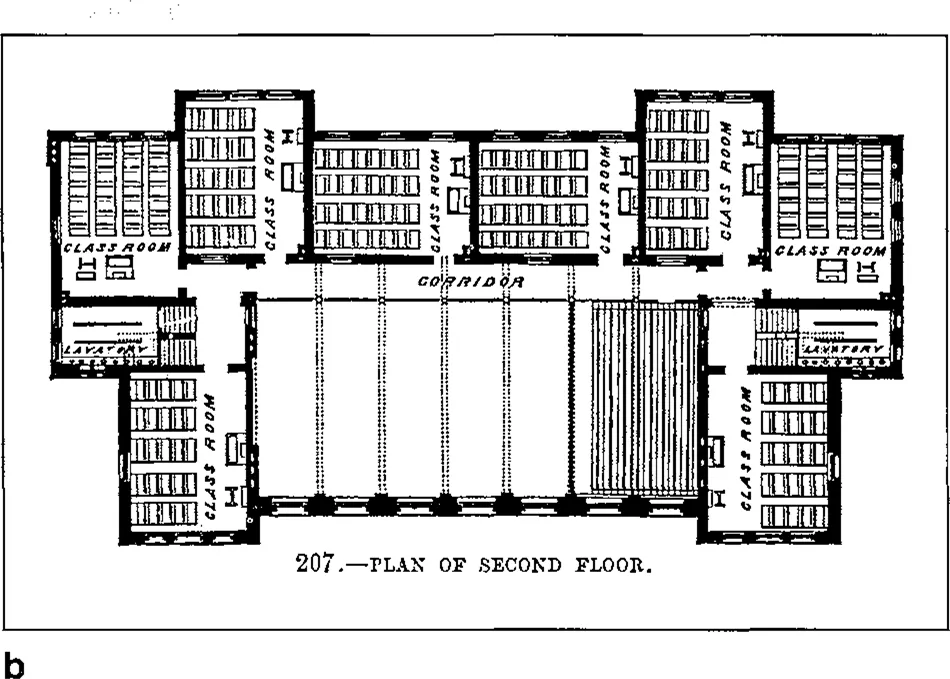

Hall describes this conception as fixed feature space. There is no denying the effect this has upon the psychology of the child, indeed on our society as a whole. Winston Churchill’s oft repeated dictum, ‘We shape our buildings and they shape us’ is never more apposite than when it is applied to the first schools.3 Austere they may have been, but the first board schools designed by E.R. Robson inadvertently adopted a model based around the form of the eighteenth century house, with individual (class) rooms, clearly articulated circulation routes and a large assembly hall at its heart. They had an ordered configuration which was an essential characteristic of the educational process itself, establishing a framework for both. Many aspects of this conjunction prevail to this time.

(School Architecture, E.R. Robson.)

This interpretation can also be applied to the wider urban environment. For example, the ways in which civic buildings such as town halls, churches, prisons and recreational buildings assumed a particular architectural language, which helped to impose a social hierarchy upon the nineteenth century city. This could be seen particularly in the architectural styles adopted for the earliest elementary schools in England at that time, with the use of Tudor gothic for the Anglican Proprietary schools in towns such as Sheffield, Liverpool and Leicester. This was often countered by nonconformist schools in the same towns adopting italianate or Palladian styles. Whatever the style, the end result was one of calm, slightly overbearing order, a reflection perhaps of the existing social hierarchy.

Although the styles reflected an interdenominational rivalry, the school spaces themselves were essentially similar, exhibiting the primary characteristics of that most essential example of fixed feature space, the nineteenth century schoolroom. For urban children, exuberance and pure unadulterated play were the domain of the pre-school, the home environment and the street. The school house was intended to be a sober antidote to this, with a single school master imposing strict discipline. The extent to which it is appropriate to determine the form of a classroom on the basis of control is a debate which will be developed in more detail in Chapter 2. However, the notion of a fixed feature space as deterministic as the early schoolroom was, I will argue, central to the actual form of the education.

If the school is essentially concerned with imposing discipline, this conjures up the notion of children being moulded through education to be factory fodder, which would clearly neutralize the potential for school to develop creativity and freedom of expression as part of the educative process. Relating a specific range of functions to a particular space, such as a classroom, in too precise a structure is analogous to the architectural design guide complete with its so-called ‘generic plans’. It can smother creativity for both the architect designing the space and the teacher who must use it as the context for teaching, since the plans can be copied to create a single model which takes no account of the context, the physical and social particularities of the site or the creative aspirations of its designer.

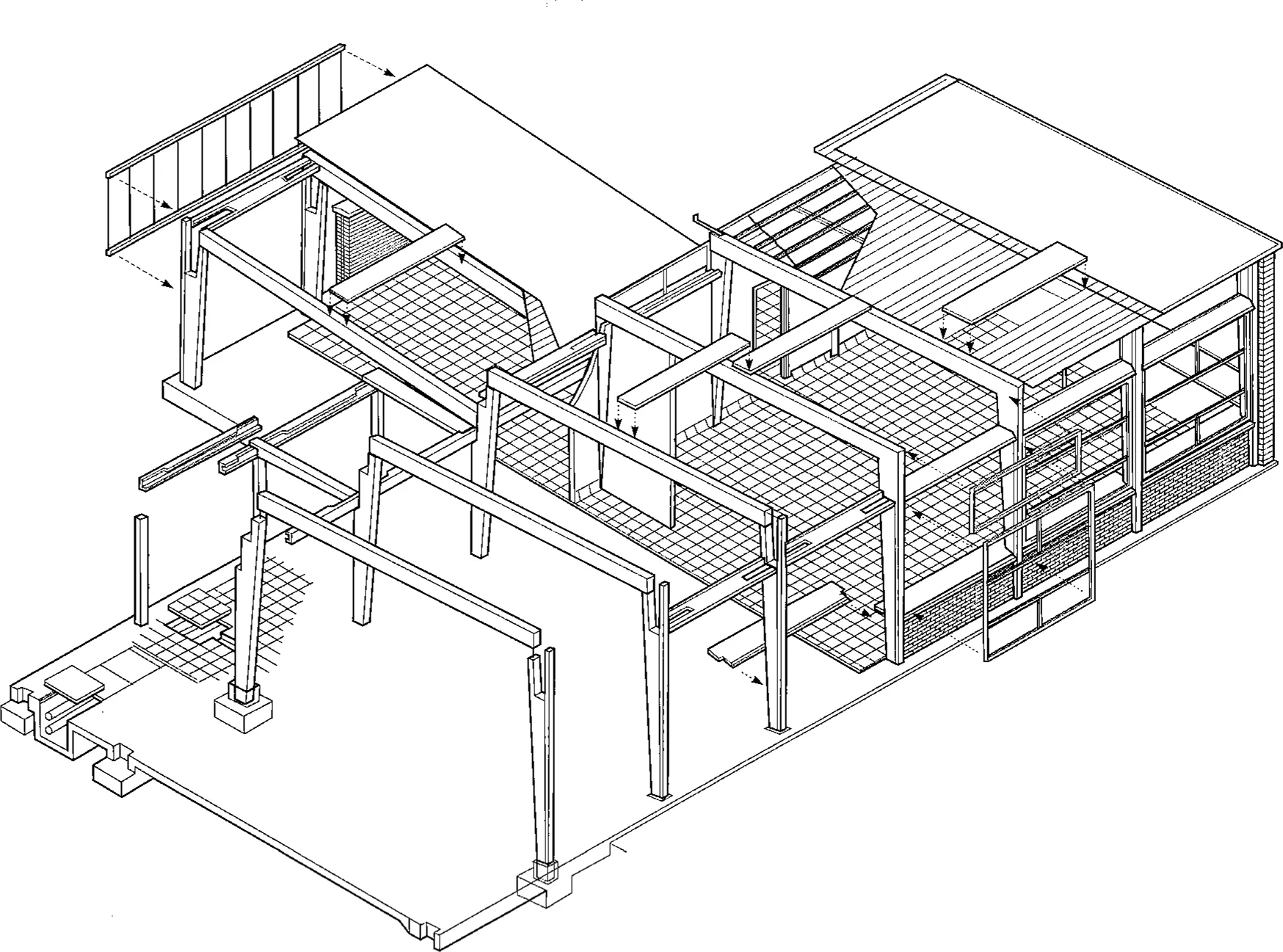

To reiterate, the overriding need to provide for large numbers in education is and remains the prevailing requirement throughout the first two hundred years of school design. The constructional technology adopted ranged between two extremes: on the one hand, heavy traditional structures, which were robust but inflexible. On the other extreme, lightweight modernist conceptions which were quick and relatively cheap to build, but had all kinds of constructional and environmental shortcomings. A similar educational dic...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword by Bryan Lawson

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part A Education and the Environment

- 1 Origins and significant historical developments

- 2 The educational curriculum and its implications

- 3 Making the case for architecture in schools

- 4 The community in school and the school in the community

- Part B Case studies

- 1 The Speech and Learning Centre, Christopher Place, London

- 2 Seabird Island School, Agassiz, British Columbia

- 3 Strawberry Vale School, Victoria, British Columbia

- 4 Westborough Primary School, Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex

- 5 Woodlea Primary School, Bordon, Hampshire

- 6 Anne Frank School, Papendrecht, The Netherlands

- 7 The Bombardon School, Almere, The Netherlands

- 8 Pokesdown Primary School, Bournemouth

- 9 Ranelagh Multi-Denominational School, Ranelagh, Dublin

- 10 Little Village Academy, Chicago, Illinois

- 11 Saint Benno Catholic Secondary School, Dresden

- 12 Haute Vallée School, Jersey

- 13 Elementary School, Morella, Spain

- 14 Admiral Lord Nelson Secondary School, Portsmouth, Hampshire

- 15 Heinz Galinski School, Berlin

- 16 North Fort Myers High School, Florida (Additions and Renovations)

- 17 Albert Einstein Oberschule, Berlin

- 18 Barnim Gymnasium, Berlin

- 19 Odenwaldschule, Frankfurt (Extension)

- 20 Waldorf School, Chorweiler, Cologne

- Index