- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introducing Race and Gender into Economics

About this book

Economics has tended to be a very male, middle class, white discipline. Introducing Race and Gender into Economics is a ground-breaking book which generates ideas for integrating race and gender issues into introductory eocnomics courses.

Each section gives an overview of how to modify standard courses, including macroeconomics, methodology, microeconomics as well as race and gender-sensitive issues. This up-to-date work will be of increasing importance to all teachers of introductory economics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introducing Race and Gender into Economics by Robin L Bartlett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Integrating race and gender: a framework

This part of the book is an introduction to integrating race and gender issues

into an introductory economics course. Robin Bartlett, in “Reconstructing

Economics 190 R&G: Introductory Economics from a Race and Gender

Perspective,” discusses a way to begin reconstructing an introductory economics

course within the framework of course development. This chapter reviews

the four elements of course design and discusses where race-and gender-related

issues may play a part in encouraging or discouraging students in the subject.

It includes an examination of how economics is communicated to students

on the first day of class through the demographic characteristics of the professor,

the course syllabus, and textbook. It looks at the interactions between the

professor and the student and how those first impressions are important,

particularly for the non-traditional student of economics.

Next, the Macintosh model of integrating race and gender into any course

is presented. The five interactive stages of the Macintosh model are developed

and a new, more inclusive course syllabus for introductory economics is presented.

The new course syllabus not only explicitly mentions race and gender issues,

but also outlines how the material will be presented and how students will

be evaluated. A unique feature of the course is its pedagogy. Students are

given the option of taking the course by themselves or as part of a cooperative

group as a team.

While the syllabus presented is still work in progress, it provides some

suggestions of the changes it is necessary to make with respect to content,

methodology, and pedagogy.

1 Reconstructing Economics 190 R&G: Introductory Economics course from a race and gender perspective

Robin L.Bartlett

On the first day of introductory economics, students form impressions of their instructor and of economics. Their first reactions to instructors and their more visible characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, age, dress, and able-bodiness are important. From these reactions, students form opinions and expectations about their instructors. On the first day of class, students also form first impressions about economics and whether or not they will like it. They form these opinions and expectations from reactions to the course syllabus and from the required textbook(s). Students examine these documents and try to figure out what they will learn, how they will learn it, and what will be expected of them. Finally, students watch how the instructor interacts with different students, and in particular, with themselves. They do a quick cost/benefit analysis and either keep the textbook(s) or fill out a drop-add slip.

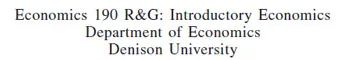

AN INTRODUCTORY ECONOMICS COURSE SYLLABUS

While little can be done to change students’ first impressions of their instructor, this book will focus on students’ impressions of introductory economics and how it is taught from a race and gender perspective. The course syllabus displayed in Figure 1.1 is typical of ones for one-semester introductory economics courses. Syllabi for two-semester or two-quarter courses focus on either introductory microeconomics or macroeconomics each term and tend to cover more topics. Independent of course length, however, most syllabi look remarkably similar. Key bits of information about the time, meeting place, and instructor are located at the top of the first page. Course objectives, if explicit, are outlined under the course title and number. A list of required texts follows, along with a schedule of dates and chapters to be covered on these dates. Sometimes the chapter headings are included to indicate topics. At the end of the syllabus are course requirements: the number of exams to be taken, the weight given each exam in calculating the student’s final grade, and other course assignments such as readings, quizzes, short papers, bonus points, etc. Course syllabi often read as if they were legal documents. Rarely do introductory economics course syllabi paint a very exciting and inclusive picture of what students will learn in coming weeks and how they will go about learning.

Figure 1.1 A syllabus: Economics 190 R&G: Introductory Economics

Instructor: Robin L.Bartlett

Office: Knapp 210

Office Hours: 1:30–2:30 MTWR

Phone: X6574

Required Texts:

Bailey, Jennifer L. and Thompson, Judy A. Understanding Economics Tomorrow, tenth edition (Granville, OH: Doers, 1996).

Course Goals:

- To learn the basic concepts and definitions used by economists.

- To learn the basic models of supply and demand used by economists.

- To learn how to apply the basic models of supply and demand to economic issues and problems.

Course Outline:

August 29 to September 2

- Day 1 Introductions and Expectations

- Day 2 The Science of ChoiceChapter 1

- Day 3 ScarcityChapter 2

- Day 4 Global ScarcityChapter 2

September 5 to September 9

- Day 1 The Law of DemandChapter 3

- Day 2 Changes in DemandChapter 3

- Day 3 The Elasticity of DemandChapter 3

- Day 4 The Law of SupplyChapter 4

September 12 to September 16

- Day 1 Changes in SupplyChapter 4

- Day 2 The Elasticity of SupplyChapter 4

- Day 3 Supply and DemandChapter 4

- Day 4 Market AnalysisChapter 5

September 19 to September 23

- Day 1 Price Controls Chapter 5

- Day 2 Quantity Controls Chapter 5

- Day 3 Review for Hourly Exam Chapter 5

- Day 4 First Hourly Exam

September 26 to September 30

- Day 1 Return and Discussion of First Hourly Exam

- Day 2 Production Chapter 6

- Day 3 Profits Chapter 6

- Day 4 Marginal Analysis Chapter 6

October 3 to October 7

- Day 1 Marginal Costs Chapter 6

- Day 2 Marginal Costs and Price Chapter 6

- Day 3 Monopoly Chapter 7

- Day 4 Monopoly vs. Competition Chapter 7

October 10 to October 14

- Day 1 Factor Markets Chapter 8

- Day 2 Changes in the Demand for Labor Chapter 8

- Day 3 Unions and Wages Chapter 8

- Day 4 Market Failures Chapter 9

October 17 to October 21

- Day 1 Government Intervention Chapter 9

- Day 2 Poverty Chapter 9

- Day 3 International Trade Chapter 10

- Day 4 Free Trade Chapter 10

October 24 to October 28

- Day 1 Review

- Day 2 Second Hourly Exam

- Day 3 Return and Discussion of Second Hourly Exam

- Day 4 Aggregate Economic Activity Chapter 11

October 31 to November 2

- Day 1 Past Periods of Growth Chapter 11

- Day 2 Business Cycles Chapter 12

- Day 3 The Circular Flow Chapter 12

- Day 4 No Class

November 7 to November 11

- Day 1 Government Policies Chapter 13

- Day 2 Taxes and Outlays Chapter 13

- Day 3 Money and Interest Rates Chapter 14

- Day 4 The Demand for and Supply of Money Chapter 14

November 14 to November 18

- Day 1 The Fed Chapter 15

- Day 2 Monetary Policy Chapter 15

- Day 3 Review for Third Hourly Exam

- Day 4 Third Hourly Exam

November 21 to November 25-Thanksgiving Break!

November 28 to December 2

- Day 1 Return Third Hourly Exam

- Day 2 Economic Disagreements Chapter 16

- Day 3 Who is Right? Chapter 16

- Day 4 No Class

December 5 to December 9

- Day 1 Inflation and Unemployment Chapter 17

- Day 2 Growth Chapter 18

- Day 3 Stabilization Chapter 19

- Day 4 Wrap-up and Evaluations

December 12 to December 16

- Day 1 Final Exam 9:00–11:00 am (Section 04)

- Day 2 Final Exam 9:00–11:00 am (Section 06)

Course Requirements:

- Three Hourly Exams (100 Points Each) 300

- A Final Exam (200 Points) 200

- Class Participation (100 Points) 100 TOTAL POSSIBLE POINTS 600

Calculation of Course Grade:

| Percent of Total | Minimum Point | Grade |

| 97–100 | 582+ | A+ |

| 92–96 | 552+ | A |

| 90–92 | 540+ | A− |

| 87–89 | 522+ | B+ |

| 83–86 | 498+ | B |

| 80–82 | 480+ | B− |

| 77–79 | 462+ | C+ |

| 73–76 | 438+ | C |

| 70–72 | 420+ | C− |

| 67–69 | 402+ | D+ |

| 63–66 | 378+ | D |

| 60–62 | 360+ | D− |

When planning a course, introductory instructors usually find an old syllabus from a previous semester or borrow one from a colleague who has just taught the course. Before putting pen to paper, or fingers to key-board, however, take a close look at an introductory economics course syllabus or the one found in Figure 1.1. Use a highlighter pen to mark those places in the syllabus where race and gender issues are explicitly mentioned. If the syllabus is like the one presented above, this task will not take long.

Next, open any introductory economics textbook and count the number of times race and gender issues are mentioned in the first chapter, or even in the next ten chapters. Go to the textbook’s index and find where race and gender issues are mentioned. How often do the words “women,” “race,” or “ethnicity” appear? Feiner and Morgan (1987) did such an analysis and found that race and gender issues were rarely mentioned in introductory economics textbooks, and when they were, they were often found in separate chapters on “women’s issues” or “minority concerns.” Feiner and Morgan also found that, while sexist language was avoided, women and people of color were often included in stereotypic ways when economic concepts were illustrated. An update of the Feiner and Morgan study showed that little progress had been made (Feiner 1993). An unbalanced representation of women and people of color is not unique to economics. Rosser (1990) found the same problems in a select set of science textbooks in which gender-neutral presentations were accompanied by examples and illustrations which were frequently stereotypical.

The introductory economics course syllabi and textbook are two important vehicles for communicating to students what economics is all about. The syllabus serves as a road map—informing students of what road the instructor is going to take them down (what topics will be covered) and how they are going to travel it (the pedagogy). The text serves as a reference manual—a reservoir of economic concepts—a detailed write-up of the terrain to be covered. A quick look at the introductory economics syllabus and a flip through the pages of an introductory economics textbook may give students the wrong impression of economics as a subject with little to say about race and gender-related issues. If the subject with its limited textbook applications is still of interest to them, the graphical or mathematical presentation of economics may be less attractive to some students than the methods of theorizing in other subjects. As a result, good students may shy away from economics (Bartlett 1995).

The introductory economics course syllabus and textbook are not the only vehicles for communicating economics to students. Instructors “talk” in a variety of ways to students. An instructor communicates both verbally and non-verbally to students enthusiasm about the subject matter, about which students the instructor values, and about which students the instructor expects to succeed. Students who decide to give economics a try may find that the actual day-to-day classroom experience is one that tells them that economics is not a welcoming or supportive classroom for them.

The literature shows that many of the interactions between instructor and student are predicated upon gender- and race-related stereotypes, encouraging preconceived ideas about certain students’ abilities and talents. Thus, the classroom dynamics between the instructor and the students, and among the students themselves, play significant roles in determining which students find economics of interest.

Inclusive teaching is about improving lines of communication through printed materials and better student/faculty and student/student interactions. Inclusive teaching is about communicating a realistic picture of our economy, effectively, to all students.

Facing the fears and “What if” questions

Incorporating race and gender issues in the classroom is challenging. A whole array of fears and “What if” questions surface. For example: Where do I find material on race and gender issues without going back to graduate school? When will I find the time to read, understand, and assimilate the new literature on race and gender differentials? Don’t race and gender issues belong in an economics of discrimination or labor economics course? I am not a racist, yet race is a “touchy” subject to bring up in class. I have two daughters, so I don’t treat female students any differently than I treat male students. If I spend time on race and gender issues, my students will not know the material they need to go on. Key topics have to be covered, so my students are ready for intermediate microeconomics and macroeconomics. If I start discussing “women and minority issues” in introductory economics, my colleagues will think I am being too political. What if I use a politically incorrect term? What if someone wants to talk about sexual orientation? And the “what ifs” go on.

How to proceed

Since introductory economics instructors have a wide range of backgrounds in course development and women’s and minorities’ studies, this discussion starts with a focus on issues of course design and how race and gender can be introduced with a variety of delivery and evaluative strategies. This section will look at pedagogical strategies for delivering the course content and methodology and for evaluating students’ comprehension of the material. Then the McIntosh model of integrating race and gender issues into a discipline will be developed as one way to integrate race and gender issues into the present course content and methodology of introductory economics. This section will present a revised introductory economics course syllabus that more effectively...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Preface

- Part I Integrating race and gender: a framework

- 1 Reconstructing Economics 190 R&G: Introductory Economics course from a race and gender perspective

- Part II Integrating race and gender topics into introductory microeconomics

- 2 Protective labor legislation and women’s employment

- 3 Market segmentation: the role of race in housing markets

- 4 Gender and race and the decision to go to college

- 5 The labor supply decision—differences between genders and races

- 6 The economics of affirmative action

- 7 Risk analysis: do current methods account for diversity?

- Part III Integrating race and gender topics into introductory macroeconomics

- 8 Race and gender in a basic labor force model

- 9 General vs. selective credit controls: the Asset Required Reserve Proposal

- 10 A critique of national accounting

- 11 A disaggregated CPI: the differential effects of inflation

- 12 An active learning exercise for studying the differential effects of inflation

- Part IV Additional considerations in integrating race and gender into Economics 190 R&G

- 13 Gender and the study of economics: a feminist critique

- 14 Integrating race and gender topics into introductory microeconomics courses

- 15 Thoughts on teaching Asian-American undergraduates

- 16 Some thoughts on teaching predominantly affective-oriented groups

- 17 Race, gender, and economic data