- 355 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

EuroDiversity

About this book

How has cultural diversity affected the business climate of the growing European Union? What are European institutions and enterprises doing to manage it? In 'EuroDiversity,' Dr. Simons gathers issue-centered perspectives on how Europe's entwined past, present, and future have made it the most strikingly diverse part of the world and what this means for doing business there. 'EuroDiversity' provides:

* Insights into Europe's cultural challenges of globalization, diversity dilemmas, and opportunities

* Case studies, best practices, and resources for finding the common ground and developing the competence needed to succeed

'EuroDiversity' addresses how cultural diversity affects the business climate of the growing European Union and describes what European institutions and successful organizations are doing to manage it. The book's multinational team of authors gives us issue-centered perspectives on how Europe's entwined past, present and future have made it the most strikingly diverse part of the world and what this means for doing business there. They address Europe's cultural challenges of globalization and provide abundant insights into diversity dilemmas and opportunities. They point to the best practices and resources that will assist both European enterprises and those actively present in or trading with Europe to find the cultural common ground and competence they need to succeed.

Contributors: Arjen Bos, Marie-Thérèse Claes, Ph.D., Elena A. A. Garcea, Ph.D., Nigel Holden, Ph.D., Michael Stuber

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

BetriebswirtschaftSubtopic

Business allgemein1

Patchwork: The Diversities of Europeans and Their Business Impact

Historically, Europe, or “the Old World,” is different from the lands in which European emigrants settled and made their own. Europe has always been very diverse, and Europeans are fully conscious of their diversity. They differ from North Americans in what to do about it. In the best of times, Europeans believe that “good fences make good neighbors.” In the worst of times, those who attempt to create or reshape these boundaries discover that they have been painted in blood.

At the outset, particularly for non-Europeans, it is important to keep telling ourselves that “Europe is a continent not a country!” As U.K. diversity specialist Graham Shaw reminds us, Europe contains many different models of social and political organization—including the European Union, to which not all states adhere. Each differs in its commitment to the social support of its population, and legal systems differ both in style and content when it comes to if and how they regulate what we may identify as diversity issues (Shaw, 2000, p. 12).

Diverse by nature, the European Union got its start in the search for peace and prosperity after history's most devastating war (World War II, 1938–1945). While Canada and the United States may have discovered the bottom line challenge of diversity in the unused potential of their disadvantaged people, Europe started with the commercial bottom line as a reason for managing its differences. North American diversity started with social and government initiatives that extended into the private sector; in Europe, economic cooperation among diverse peoples was the starting point. Only later did this cooperative enterprise begin to take responsibility for a social and cultural European integration whose necessity, utility, and desirability continue to be questioned every step of the way.

Exhibit 1.1 Piet Mondrian, “Composition with Red, Yellow, and Blue” 1921, oil on canvas, cm 39.5 × 35

Patchwork. An image, a metaphor is needed to grasp the complexity of European history, culture, and the contemporary challenge of creating value from the enormous diversity of this place called Europe.

Patchwork. Something cobbled together of bits and pieces, respecting the nature and possibilities of each, and creating fresh value and utility. A patchwork quilt that keeps us safe and warm.

Patchwork. Something that can be added to; pieces that can be rearranged if necessary. The look and feel of Europe; the Mondrian perspective (Exhibit 1.1) one gets while flying over much of it; and the clear boundaries of the E.U. Member States with the now abandoned customs houses one sees when driving across borders.

Patchwork. The result of imagination and compromise, today more often hastily sewn together by corporate expansion, mergers, and acquisitions than by politics and policies.

Source: The Haag's Gemeentemuseum.

This does not mean that Europe has lacked or lacks either humanitarian motivation or social concern for its diversity. There are countless local, regional, national, and supranational governmental efforts as well as abundant NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) and private initiatives for assisting the continent's disadvantaged, its asylum seekers, and those targeted by bias and racist violence. We shall be paying attention to how these affect and support related business policies and activities.

The Challenge of Cultural Diversity

In what ways is cultural diversity a bottom-line challenge for European businesses and those doing business in Europe, and what does managing diversity involve? In European businesses these questions are being asked more and more often. Charles Black, Medical Director of NovoNordisk Europe, points out that the cultural challenge facing modern business managers is in many ways new (Black, 2001, Introduction, p. 1). He sees this fresh challenge as one brought about by globalization and the technological revolution in communications and travel. According to Black, global managers should be asking themselves,

How can I…

1. maintain strong corporate strategic alignment in the face of increasing cultural and personal diversity in the company workforce?

2. find opportunities in cultural diversity to better meet my need to be responsive to my global and culturally diverse customers?

3. learn to deal with cultural diversity in other stakeholder groups, notably my shareholders?

4. harness and manage cultural diversity to enhance innovation?

(Black, 2001, p. 2–3)

For organizations that would operate in a global environment, managing culture is also an essential part of the inevitable and constant change process. Black likens this to a child growing into adulthood:

Most companies have an organization that is derived in part from the national “parent” culture from which they originate…. [T]he globalizing company must free itself of its own home country cultural heritage with all its inherent limitations to manage a global business. In the process, it must keep the beneficial aspects of that culture while ridding itself of the negative ones.

(Black, 2001, p. 3)

Our U.S. and Canadian colleagues who have been engaged in national debates on diversity for years now look at the incredible diversity on the continent of Europe and scratch their heads in amazement that the word “diversity” itself has been, until recently, so rarely mentioned here. Equivalent terms like kulturelle Vielfalt (cultural diversity) and gerer diversite (managing diversity) have been used in Germany and France, respectively, but almost always to discuss North American diversity. Why then has diversity not been the “hot topic” in Europe that it is in North America? The answer is that the issues have been very important ones, but they have been conceived of and dealt with in a different form of discourse. We are not questioning whether diversity exists or diversity initiatives make sense for European businesses, but we are asking how and when do they do so. What are the differences? How have they been dealt with, and how should they be dealt with? To answer these questions we need to look for insights in the history and culture of Europe.

A History of Assimilation

While the E.U. as a whole is extremely multicultural, its Member States and regions are traditionally far more monocultural than are the United States and Canada, for example. This requires some qualification, as within each country there is a highly diverse mixture of assimilated ethnicity over the centuries. Wars, treaties, dislocations, and intermarriage make Europeans a very mixed bag in terms of bloodlines, but not in their sense of national and ethnic identity. It sheds little light on the subject to learn that, for example, Greeks and Turks are virtually identical at the genetic level, or that 80% of all Europeans are descended from a common ancestor. In other words, assimilation has been occurring and continues to occur as a managing diversity strategy. Even in a country with such a liberal reputation as the Netherlands, the pressure on today's immigrants to the Netherlands and other European countries to learn the national language and culture is much stronger than would be politically possible in the United States or even Canada. Businesses, of course, benefit from these policies by getting entry-level workers who are easier to communicate with and instruct.

Assimilation strategies are part of a monocultural mentality resulting from long-defended boundaries and can even be a conscious strategy in countries with plural language cultures like that of Switzerland. Where assimilation has been unsuccessful, usually as a result of forced political settlements, regional cultures assert themselves, and resentment and even open hostility are always possible. Northern Ireland and the former Yugoslavia are the most current examples of this, but smoldering resentments still exist in Belgium and Spain and wherever historical ethnicity and regional autonomy are still at odds with national unity.

Assimilation strategies have also been taking place in businesses as well, with English as the corporate language of many large organizations despite their country of origin or the location of their headquarters. Meeting each other on the common ground of English is often an important strategy for not only overcoming the Babel of languages, but for sidestepping otherwise incompatible histories and cultures. Homogenization of language and assimilation to the organizational culture, however, notes Black, may have already reached its limits, as the truly savvy global manager needs both cultural knowledge and agility to apply it both internally and externally (Black, 2001).

Paradoxically, Europeans in U.S. owned or affiliated companies often resist the arrival of diversity initiatives, seeing them as assimilationism on the part of Americans and another attempt on their part to make the world over in their own image. Indeed, U.S. missionary zeal and free market ideology may accompany such efforts, as many Americans have long been convinced that it is their role to “make the world free for (their version of) democracy,” and have thus ethnocentrically evangelized the world with it. As Juan Moriera-Delgado of the Spanish Ministry of Education points out, “The American performance in the international arena casts the image of a solid political nationalism. From the outside there is unity and American nationalism. From the inside the discussion is about multiculturalism, any reference to nationalism pointing at a foreign affair” (Delgado-Moreira, 1997, electronic document at http://www.sociology.org/content/vol002.003/delgado.html). U.S. sponsored initiatives often run aground because U.S. diversity specialists lack cultural knowledge and experience in Europe, and many Europeans have a simplistic cultural understanding of the United States.

Defense of Boundaries and Frontiers

The use of the word “frontier” provides a good illustration of how the European and North American sense of boundaries differ. Michael Berry, Docent in Intercultural Relations at the Turku School of Economics in Finland, has highlighted that when a European speaks of the “frontier,” he or she refers to the nation's borders, usually in the sense of boundaries that need to be defended (1994). Traditionally, when a soldier was assigned to a country's “frontier,” it meant literally that. Such a sense of boundaries has resulted in a stricter sense of nationality and of personal national identity than North Americans are used to. In the world of business, new forms of openness, transparency, and open-door policies can be at first bewildering to Europeans. One of the diversity challenges to the European Union and European businesses has been to create the necessary openness for cooperation across traditional boundaries and to decompartmentalize business procedures.

On the other hand, when a North American speaks of “the frontier” or even “a frontier,” it usually points to a border that is meant to be crossed or an achievement that is intended to be surpassed. Indeed, the metaphorical use of the word is more common today in such expressions as “the frontiers of cyberspace”. Labeling something a “frontier” challenges the listener to make a “breakthrough”. Of course, “frontier” in North America may not roll so pleasantly from the tongues of Latinos and Native Americans or First Nations. They experienced quite differently the belief in Manifest Destiny that led European adventurers and immigrants to possess and dominate the New World “from sea to shining sea” as if it were their own or theirs for the taking.

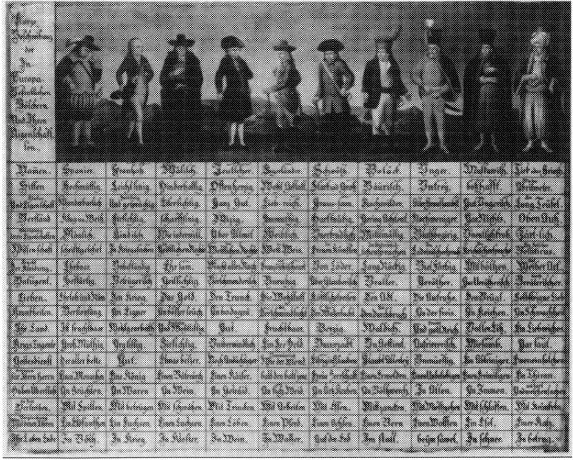

Exhibit 1.2A is an early eighteenth-century matrix showing the cultural characteristics of representative peoples found in Europe. It is interesting to note that this antique “snapshot” of Europe includes Central Europe as well as Turks and Greeks who are lumped together. German-speaking peoples are treated as a single category. Political boundaries have changed since then and, if anything, became more fiercely delineated in the twentieth century. We have attempted to translate this chart in Exhibit 1.2B, to illustrate how distinctly Europeans saw each other at that time and also to show how many of the characteristics and stereotypes mentioned then are still quite common almost two centuries later.

Exhibit 1.2 (A) Early Eighteenth-Century Description of European Peoples from the Austrian Museum of Folk Life and Folk Art, Vienna; (B) Early Eighteenth-Century Description of European Peoples (this is an English translation of Exhibit 1.2A)

(B) A Short Description of the Peoples Found in Europe and Their Characteristics

In June of 2000, the University of Central Lancashire held an international, interdisciplinary conference about current tensions in the representation of “Britishness” (Relocating Britishness, June 22–24, 2000). The themes were wide ranging, but it was clear that despite changing roles, the devolution of government in Scotland and Wales, and ambivalence about participation in the European Union, Britain contained a variety of regional and class identities that have been heightened by the need to accommodate immigration and diversity. Traditional stereotypes of Britain as the colonial power, the agent of the industrial revolution, the home of courtly society, and the tourist destination often obfuscate these real identities (see Lorbiecki and Hutchings, 2000). Simply put, a sense of identity is a contemporary hotspot in the discussion and practice of diversity, and not only for Brits, as we will show toward the end of this book. Contrary to, and perhaps as a result of the U.S. experience, in which diversity practice belatedly and grudgingly admitted white men as potential partners in and subjects of diversity initiatives, diversity work in Europe will be, and needs to be, an inclusive discussion from the beginning.

Languages as Boundaries

I recently spent over four years living and working in the Netherlands. Driving 200 kilometers from home in any direction, I was not able to speak my newly acquired Dutch with much likelihood of being understood. I grew up in Cleveland, Ohio in the United States. From my native town, I could drive a thousand or more miles in any direction with the almost sure expectation of being understood. These odds were pretty good even if I happened to temporarily find myself in rural Quebec or passing through an ethnic or immigrant enclave.

A Belgian colleague told me quite a different story:

We use over a dozen languages in the European Union. Most of us in business speak one or more second languages. The meaning of words and phrases can differ very much. We have used this linguistic diversity to protect local markets, products, and economies. Most young Europeans, in fact, do not speak another language well until they are about 14 to 16 years old, well beyond the critical age where they still influence each other at a fundamental cultural level. The dominant language groups do not subtitle films and television broadcasts but synchronize the speech. We have had wars and economic disputes to reinforce linguistic divisions and stereotypes. Religious segregation can complicate matters further.

Language reinforces boundaries in Europe. While English has, paradoxically, become the lingua franca of international business, most of Euro...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Series Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1. Patchwork: The Diversities of Europeans and Their Business Impact

- 2. The Legacy of the Past: How National and Regional Differences Continue to Effect Trade, Cooperation, Politics, and Relationships

- 3. Current Cultural Crises, Fears, Fantasies, and Foreseeable Futures

- 4. Managing Diversity to Create Marketable Value Added from Difference

- 5. Europe Online: The “New” Economy and Virtual Collaboration from a Cultural Perspective

- 6. Corporate Best Practice: What Some European Organizations Are Doing Well to Manage Culture and Diversity

- 7. The Cross-Cultural Transfer of Best Practices: Learning from European and American Experiences of Knowledge Management

- 8. Sustainable Entrepreneurship in a Changing Europe: Pedagogy of Ethics for Corporate Organizations in Transformation

- 9. Equal Opportunities for Women and Men in the European Union: The Case of E-Quality in Belgium

- 10. Who Is the European? Prognosis and Recommendations

- Resources

- Internet Resources

- Appendix 1. Declaration on Cultural Diversity

- Appendix 2. Commission of the European Communities

- Appendix 3. Declaration on a European Policy for New Information Technologies, Budapest, 7 May 1999

- Appendix 4. Survey of Diversity Challenges in the E.U. Region

- Appendix 5. Benchmarking Initiative

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access EuroDiversity by George F. Simons in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.