- 255 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The AutoCADET's Guide to Visual LISP

About this book

AutoCADet: A person who uses AutoCAD directly or indirectly to create or analyze graphic images and is in possession of one or more of the following traits: wants to learn; has an interest in improving the way AutoCAD works; is a visionary AutoCAD user; i

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Big Picture

When using a tool, it can be helpful to know where it originated, so this chapter begins with a brief history of Visual LISP. Next, you learn about the AutoCAD family of programming options

blocks and menus; scripts and DIESEL; Visual LISP, ObjectARX, and Visual Basic so that you can understand why some think Visual LISP is the best choice for most AutoCAD customizations. The chapter concludes with some advice on getting started programming in Visual LISP.

The History of Visual LISP

Visual LISP is derived from the LISP language, which was defined back in the late 1950s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). LISP was an experiment in reducing the time required to define a problem to the computer. The underlying idea was that future computers would be significantly faster and capable of handling vast amounts of data as well as processor instructions. Therefore, longer processing time and increased resource usage would not matter, but the cost of the people needed to define problems would. (This vision was extraordinary when you consider that it was made during the 1950s, when the few computers that were in existence had little processing power and disk space by today's standards.) The experiment was a modest success. Meanwhile, advances were being made with private industry tools such as FORTRAN from IBM. Because LISP required a lot more computing power than most people had at their disposal and because it was the result of university work with no company standing behind it, the language remained an idle curiosity taught to computer scientists.

LISP versus other languages

LISP differed from other languages in several ways. First, most programming languages convert source code to assembler or the machine language of the processor. LISP, however, is evaluated, which means each line of a program is read and processed as it is supplied to the computer. Although this approach is much slower during program execution, it gives a program the capability to change itself during execution. That meant LISP programs could be adapted in ways other programming languages could not.

The second way that LISP differed from other programming languages was in its syntax. Computer languages had two basic formats: machine language or algebraic. Machine language formats contained an operation followed by a single value or a memory reference to a value. Algebraic formats appeared more like written formulas of numbers and variable values. LISP combined the two formats by having an operation followed by any number of values, references, or other statements. This syntax form is often called prefix, notation.

LISP's prefix notation led to the use of another distinguishing feature of LISP: parentheses. The various logical parts of a LISP program are separated by parentheses. Each statement in LISP starts with an open parenthesis followed by the operation. If the operation includes arguments (variable values and references), they follow the operation name, separated by spaces. A closing parenthesis marks the end of the statement. The complete statement, including the parentheses, is called an expression. A key item to keep in mind about expressions is that they always return a value.

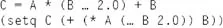

The parentheses get interesting when you consider that you can have expressions inside expressions. (This is why some people say that LISP means Lost In Stupid Parentheses.) For example, the following expressions produce the same answer, but one takes a bit longer to read:

The first example is how the expression might appear in Visual Basic, C++, or FORTRAN. The second expression is how it appears in LISP. To read the second expression, go to the innermost parentheses, (… B 2.0), which says, “B minus 2.” The operation is first, followed by the variables, values, and expressions. After computing the result, go out another level of parentheses to where that value is multiplied by the value of A. Then go out another level to where B is added to the result.

Although this approach is difficult to read, it makes good programming sense. When you provide a program expression, the computer does two things: evaluates the expression and then computes the instructions. When evaluating, the computer reads the entire expression and checks to make sure it can recognize the outermost components. All it checks at first is that you have a valid expression matching parentheses and an operation followed by values or expressions. Then it looks at the first operation. This tells the evaluator (the program running in the computer that accepts your program input in LISP) what to expect next in the way of parameters or operands.

For example, if the expression starts with (+, the evaluator expects to find at least one number following the plus operation. The evaluator puts that operation request on the system stack and examines the arguments. (A stack is a storage strategy that works like a stack of plates: the first thing stored is the last thing used.) If an argument starts with a parenthesis character, it is evaluated and the result is saved on the stack with the operation that started the process. If the next input item is a value, it is used directly. This process continues until the closing parenthesis is encountered. At this point, the data is available for the operation to take place.

Don't worry if you didn't follow all that; I discuss this concept again later in the book. For now, note that the LISP syntax allowed the computer to quickly handle program code as an evaluator.

LISP to Visual LISP

Because of LISP's memory requirements, it was not a popular programming language for the development of commercial products through the 1960s and 1970s. However, the fact that LISP had an evaluator driving the execution of programs that could change as needed was useful in a variety of application environments, including artificial intelligence, adaptive systems, and robotics.

During the 1970s and 1980s, LISP was ported to smaller and smaller computers as they became available at universities and colleges. One of these versions, written in C and called XLISP, was posted on CompuServe in the High-Level Languages forum. (CompuServe was an extensive computer network service where you could trade files and messages.) A systems programmer from Autodesk retrieved the file, which was quickly integrated into AutoCAD.

Over the next year, Autodesk continued to refine LISP, producing a powerful language called AutoLISP. The earliest releases of AutoLISP were simple versions of what is now Visual LISP. The basics of LISP were provided along with a minimal capability to interface with the user and the AutoCAD command processor. You could write a program that accepted input from the user and then drew new geometry; this in itself was powerful.

In later releases of AutoLISP, programmers could read and write data to the current drawing. This feature created a boom of new applications as engineers and architects learned the language and began to exploit the programming powers of AutoCAD.

Autodesk then released the ADS (Autodesk Development System) library, which enabled C programs to communicate with AutoLISP. ADS was followed by ObjectARX, which could do everything ADS did and more. Autodesk stated that in the future everything would be accomplished with ObjectARX — and to many this appeared to be AutoLISP's death call.

Shortly after ADS was first available, a group of European developers began using a new programming tool: a replacement for AutoLISP that became known as the European Compiler. This compiler created FAS files from LSP files, resulting in programs that were not only reported to run four times faster but were also encrypted, which helped prevent piracy of AutoLISP-based applications. But the European Compiler didn't catch on immediately, especially in the United States, because it wasn't from Autodesk and it didn't appear that Autodesk would endorse it.

Undeterred, the developers of the AutoLISP compiler continued to improve it and came out with a version called Vital LISP that was packaged more as a software utility product. Vital LISP was a vast improvement over AutoLISP. Vital LISP took advantage of ObjectARX, opening the way for expansion and improvement. Virtually all of the system-level utilities that developers found lacking in AutoLISP were provided in Vital LISP. Plus Vital LISP came with a text editor optimized for LISP program entry.

Autodesk purchased the Vital LISP technology, improved it with the introduction of more than 800 functions, and repackaged it as Visual LISP. At this time, Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) was introduced into AutoCAD. This stifled the rumors that Autodesk was phasing out AutoLISP.

The result of this evolution is a powerful programming language that requires a long time to master but also enables you to begin writing simple programs in a short time.

Programming Choices in AutoCAD

AutoCAD is expensive, and some may argue that it should not need customization. But AutoCAD is powerful because it can be customized. Out of the box, AutoCAD is a great drawing tool. Graphic design and editing are easy after you learn the basics.

If you create drawings that are variations of each other, you can save complete or partial drawings and then reload and edit them. But consider the time-savings if you could automate that task.

For example, suppose that you frequently create drawings that contain circles representing attachment points for a fixture. You want to show only the holes, not the fixture. You insert the fixture, use the through-hole locations in that drawing to locate new circle centers, and then remove the fixture block. Compared to drawing the circles one at a time from other parameters, this is a great timesaver. Now consider what would happen if you wrote a program that accomplished the same task in just a few seconds. The time you'd save would quickly add up and easily justify the time you would spend creating the program.

In your own work with AutoCAD, can you identify a repetitious task something that is time consuming but requires skill rather than a lot of thought? If so, you have identified the perfect candidate for automation.

For larger installations, automating AutoCAD can turn into a full-time job. For smaller places, automation is a way to stay ahead of the competition as well as keep the job fresh and exciting.

AutoCAD can be customized in many ways to meet the needs of designers and engineers. Each customization tool has strengths and weaknesses that are not easy to identify at a glance. Some relate to you directly. Do you already know a programming language or two? Do you know how to run AutoCAD? Do you have the time to program in addition to your other job-related tasks? Following is a quick look at each of the programming options in AutoCAD.

Blocks and menus

Blocks and menus are easy to program and are often an AutoCAD operator's first step in customizing AutoCAD. Properly constructed, block libraries can save you a lot of time when you are creating drawings that have many similar components. When combined with a menu system, block libraries can become extensive.

Menus are the primary interface for the AutoCAD operator and an important part of the user's computer environment. Menus are easy to manipulate, which is why they are one of the first programming tasks that AutoCAD operators perform. If you haven't yet customized the AutoCAD menu and created blocks, give it a try. What you learn in this book will compliment that skill nicely.

Scripts and DIESEL

Blocks are not the only tools AutoCAD operators use. A sequence of commands that you repeat frequently can be scripted and placed in a menu. For example, if you frequently copy and then rotate a sequence of geometry, you can turn those tasks into a script. A script file.

Scripting is available in two ways. You can create an SCR (script) file, which is a text file containing AutoCAD commands that you can create using a text editor or AutoCAD's scripting tools. Scripts have been very useful for plotter operations, and you can still find them in many sites. As AutoCAD's user interface evolved, however, scripts because more difficult to maintain because dialog boxes sometimes changed the sequence of commands. (AutoCAD commands that contain a dialog box often also have command-line versions as well. For example, the LAYER command displays a layer dialog box. To prevent the dialog box from appearing, you add a hyphen before the command, as in -LAYER.

Using DIESEL (Direct Interpretively Evaluated String Expression Language), you can define variables and use them in your menu design. This enables you to control more of the AutoCAD environment and command execution sequence. Scripts and DIESEL are powerful tools when programming menus.

Visual LISP

Visual LISP is a powerful programming language that you can use to automate complex sequences of AutoCAD commands, perform calculations, and much more. Visual LISP, which was derived from AutoLISP, is a full-featured programming language, supporting variables, expressions, loops, conditionals, and more. You can use Visual LISP to communicate with other systems through ActiveX as well as control almost all elements of the AutoCAD system.

Visual LISP persists today despite newer tools such as Visual Basic mainly because the legacy of AutoLISP has provided a large library of useful programs and examples that can be used to create even more powerful tools in AutoCAD.

ObjectARX

ObjectARX is a set of C++ libraries for building dynamic link libraries (DLLs) that you integrate directly into AutoCAD. ObjectARX is useful for adding new commands and functions to AutoCAD, but its complexity makes it difficult for beginning programmers to use.

ObjectARX provides a tool for adding functions (called external subroutines) to the Visual LISP environment. That means you can expand Visual LISP with new commands suitable for your application. For some applications, this is the best solution to follow.

For each new release of AutoCAD, ObjectARX applications must be rebuilt and ObjectARX modules may have to be adapted. For example, AutoCAD 2000 introduced the addition of multiple documents, which were not supported in AutoCAD Release 14. This meant that ObjectARX applications had to be reprogrammed to take into account the existence of multiple open documents. The MDI (Multiple Document Interface) change also had an effect on Visual LISP and Visual Basic, but not to the same degree that it did with ObjectARX-based applications.

Visual Basic

You can use Visual Basic to run AutoCAD. In addition, a variation of Visual Basic called VBA (Visual Basic for Applications) is supplied with AutoCAD. VBA uses the same object interfaces as Visual Basic but it starts in AutoCAD. VB and VBA are powerful programming environments that rely on the ActiveX exposure (a method of accessing subroutines and variables) of other prod...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Big Picture

- Chapter 2 The Visual LISP IDE

- Chapter 3 The Essence of Visual LISP

- Chapter 4 Working with Strings

- Chapter 5 Working with Numbers

- Chapter 6 Converting Numbers and Strings

- Chapter 7 Using Conditionals and Loops

- Chapter 8 Working with Lists

- Chapter 9 Basic User Output

- Chapter 10 Basic User Input

- Chapter 11 Introducing Dialog Boxes

- Chapter 12 Working with AutoCAD Drawings

- Chapter 13 Using Selection Sets and Tables

- Chapter 14 Saving and Sharing Data

- Chapter 15 AutoCAD Interface Programming

- Chapter 16 Event Programming

- Chapter 17 Working with the Computer

- Epilogue

- Index

- What's on the CD-ROM?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The AutoCADET's Guide to Visual LISP by Bill Kramer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.