- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Today's digital production tools empower the small team to produce multimedia projects that formerly required large teams. Orchestrating a production requires more than proficiency with the postproduction tools. Final Cut Pro Workflows: The Independent Studio Handbook offers a cookbook of postproduction workflows that teams can follow to deliver an array of products to their clients. It describes appropriate postproduction workflows, team roles and responsibilities, and required equipment for some of the most common media productions.

Combining the wisdom of traditional roles and responsibilities with an understanding of how FCP facilitates a new flexibility where these roles/responsibilities can be redistributed, this book sheds light on workflow processes and responsibilities, and includes 7 real-world workflows from a diverse range of projects:

* Money-Saving Digital Video Archive

* Long-Form Documentary with Mixed Sources

* Web-Based Viewing and Ordering System

* 30-Second Spot for Broadcast

* Multi-Part TV Series with Multiple Editors

* DVD Educational Supplement

* Music Video with Multi-Cam Editing and Multiple Outputs

The book also provides access to a companion website that features additional electronic chapters focusing on Final Cut Server, Apple's powerful new media asset management and workflow automation software.

Written with a unique iconography to better convey key points and applicable to all levels of FCP users, Final Cut Pro Workflows: The Independent Studio Handbook is a vital reference tool for every postproduction house.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Final Cut Pro Workflows by Jason Osder,Robbie Carman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 What Makes Final Cut Pro Special?

When it was released in 1999, Final Cut Pro (FCP) was a revolutionary piece of nonlinear editing software. Since then, the software (and the hardware that runs it) has matured substantially—adding features and spawning a complete suite of postproduction tools, Final Cut Studio.

Most people who were already working in postproduction knew they were seeing something special the first time they saw Final Cut Pro. To people who have entered the business since then, FCP is an industry standard.

Why is that? Why did seasoned professionals sense a sea change in the first few clicks? How has this software thoroughly changed the industry in a few short years? What makes Final Cut Pro so special?

There is a simple answer to that question: money.

Final Cut Pro has consistently done more things effectively, intuitively, and inexpensively than any of its competitors. From the program's first release and through its subsequent improvements, FCP has lowered the financial ceiling on professional-quality postproduction. This chapter is about how and why this has happened.

To fully understand what makes Final Cut Pro special, why it has had such an effect on the industry, and ultimately how to get the most out of it in your own projects, we must take a brief step back and look at FCP in context.

A Brief History of Editing the Motion Picture

The invention of motion picture technology preceded the invention of editing by several years. The first “films” by pioneers such as Thomas Edison and the Lumière brothers were single shots—a passionate kiss or a parade of royalty. The Great Train Robbery (1903) is widely considered to be the first use of motion picture editing, as well as the first narrative film.

Cutting together, or editing, footage to tell a story is a concept and a process that is largely distinct from simply capturing the moving image. As with all art forms, the aesthetics and technology of editing have changed and will continue to change, but many of the base concepts remain the same.

The evolution of editing technology has followed a predictable path from film, to magnetic analog tape, to digital media, and finally to ever less expensive digital media and higher resolutions. Final Cut Pro represents a key link in this evolution, but mostly because it does well (and inexpensively) what editors have always been doing.

Originally, film editing was performed as a physical process—pieces of film were taped together. The resulting assembled piece of film was played back, and this was essentially the finished product. Fast-forward to the age of video, and the analogous process becomes known as linear editing. Linear editing is done with a system that consists of two videotape recorders (VTRs) and two video monitors. Like cutting film, this was a straightforward process of playing the desired clip on one VTR (the source deck) and recording it on the other (the record deck).

Over time, these linear editing systems became more sophisticated. They worked with high-quality video formats, were controlled by computers, and integrated with graphics systems (Chyron) to overlay titling on video. Still, the basic principles of linear editing had not changed: two VTRs (one to play, the other to record).

There was one basic limitation to this system, and it was a frequent frustration for editors. The problem with linear editing is that once you lay down a piece of video on the record tape, you can record over it, but you cannot move it or change its length (at least not in a single pass).

In the early 1980s, with the power of computers on the rise, a new way to edit was invented: nonlinear, or digital, editing. Nonlinear editing is based on a completely different concept: convert the video into digital files (digitize). Then, instead of editing videotape to videotape, edit with these digital files that allow nonlinear access (you can jump to any point at any time with no cuing of the tape).

Putting a new shot at the beginning of a sequence (an insert edit) was no longer a problem. With all of the video existing as digital bits, and not on a linear tape, an insert edit was merely a matter of giving the computer a different instruction or pushing a different button on the keyboard. If linear editing is like writing on a typewriter, then nonlinear editing is like a word processor.

The Big Three: DV, FireWire, and FCP

By the mid-1990s, digital nonlinear editing was common but expensive. Three related pieces of technology were introduced that together drastically changed the face of postproduction.

The first is prosumer digital video (generally referred to as DV, this implies the encoding format DV-25 and the tape formats miniDV, DVCAM, and DVCPRO that work with it). These new formats were smaller and cheaper than existing broadcast formats such as Betacam SP, but with nearly the same quality. DV is also a digital format, meaning that the camera replaced the traditional tubes with new digital chips, and the video signal that is laid down onto the tape is also digital: information encoded as bits, rather than the analog information. To really understand DV, one must realize that it refers to both a tape format (a new type of physical videotape and cassette) and a codec. “Codec” is short for compression/decompression or code/decode. It refers to any algorithm used to create and play back video and audio files. Chapter 5 is all about codecs, but the important thing to realize at this point is that the DV-25 specification that appeared in the mid-nineties had both a tape and codec component, and both were of a higher quality in a smaller size than had previously been possible.

The second technological advance was FireWire, or IEEE 1394, a new type of digital protocol used for data transfer. Somewhat similar to USB, FireWire allows faster communications with external devices than was previously possible. In fact, FireWire is fast enough to allow video capture directly from a DV camera into a computer without any additional hardware.

Input/Output Protocol Basics

An input/output protocol, or I/O, is more than just a cable. An I/O is really made up of three components:

- The Cable. There is a lot to a cable. Besides being the right type (FireWire, component, SDI), other considerations include the length of the cable, its flexibility, strength, and price. Considerations include maximum length, signal loss, and power use.

- The Connections. Once you have the proper cable type, it is important that this cable is actually able to plug in to the hardware you are using. Many I/O protocols allow various types of device connections. In the case of FireWire, there are actually three device connection types—four-pin, six-pin, and nine-pin connectors—and three matching cable connections. Before buying a cable, make sure to check which type your device uses.

- Transfer Methodology. This is how the devices “talk” to each other. Transfer methodology is a necessary component of any I/O protocol, even if it may go unnoticed by many users because it is usually hardwired into the circuitry of the device you are using. In the case of FireWire, it is built right into the port and is a three-layer system:

- The Physical Layer is the hardware component of the protocol that presents the signal from the device.

- The Link Layer translates the data into packets that can be transferred through the FireWire cable.

- The Transaction Layer presents the data to the software on the device that is receiving it.

This brings up another example of changing terminology. In the previous section, we described “digitizing”—the process of loading video into a computer (making it digital). The process of loading DV into a computer through FireWire is essentially the same, but it cannot properly be called digitizing because the video is already digital! (Of course, many people have continued to call this process digitizing, because that was the accepted term.) More on this process can be found in Chapter 6: Preparation.

With DV cameras and FireWire devices already becoming popular, Apple Computer released Final Cut Pro in 1999. I remember sitting in a friend's basement, with a borrowed camcorder, capturing digital video through FireWire into Final Cut Pro for the first time. Prior to that, I had used only “professional” systems, and I was amazed to see video captured onto a sub-$10,000 system (including the camera).

By the eve of the millennium, all three of these advances had been established:

- An inexpensive, high-quality video format (DV)

- A high-bandwidth data-transfer protocol fast enough to capture video directly (FireWire)

- An inexpensive but robust nonlinear video-editing program (Final Cut Pro)

This trio created the technical and market conditions for unprecedented changes in the creation of video projects at all levels.

It should be made clear that Final Cut Pro was not (and is not) the only nonlinear editing program available. However, from the beginning, certain things made FCP special. Indeed, it is FCP, and not any of its competitors, that is quickly becoming the industry standard.

The QuickTime Video Architecture

QuickTime has been around since 1991, when it was introduced as an add-on to the Mac operating system that was used for playing video. At the time, this was a major advance and there was nothing comparable. Essentially, QuickTime is a video architecture, an infrastructure that allows video to be played on a computer. The codec is the algorithm used to encode and decode the digital video; the architecture is the virtual machine that does the decoding.

Final Cut Pro utilizes the QuickTime video architecture for driving video playback while editing. Final Cut Pro is the tool; QuickTime video is the material that the tool works on. This is why the media files you use in FCP have the .mov extension—the native extension of QuickTime files. FCP is not the only Apple program that utilizes the QuickTime architecture; iMovie and iTunes work in much the same way.

Going back to the old days of film, the individual snippets of film are QuickTime files, and the machine used to cut, tape, and play back is Final Cut Pro. As we said, many of the essential principles of editing have not changed very much. If you need further examples of this, notice the language that Final Cut Pro uses (such as “clip” and “bins”) and the iconography (such as the symbols in the browser and the shape of the tools), and you will realize that the very design of the program is meant to recall traditional film methods.

What Is a Codec?

Codec means code/decode, compression/decompression, or compressor/decompressor, and is the name given to the specific algorithm used to compress a piece of audio or video. There is an extended discussion of codecs in Chapter 5. For now, it is enough to know that within the QuickTime architecture, multiple codecs are supported for different media types.

Resolution Independence

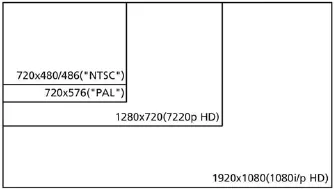

If you have used QuickTime to view video on the Web, you may have noticed that it can play back video of various sizes. This ability to work with video of different sizes is known as resolution independence, and it is something that Final Cut Pro shares with QuickTime.

This means that FCP can work with standard- and high-definition footage, and even the higher-definition resolutions used for film and digital intermediate process. It is a very versatile program in this way, and we have seen it used for off-sized video pieces as small as a Flash banner and as large as the JumboTron at the local football stadium.

This is unusual in nonlinear editing solutions, both within and outside Final Cut Pro's price range. With other editing product lines, there is often one piece of software for DV, another for uncompressed video, and yet another that handles HD. In Final Cut Pro, you may need different hardware to effectively work with different sizes and resolutions, but the software stays consistent.

Figure 1.1 Common video frame dimensions.

Resolution independence is not only a benefit for working with different types of video. It also makes for a more flexible postproduction process at any resolution. The reason for this is that Final Cut Pro can mix resolutions and work at a lower resolution for speed and to conserve disk space (higher resolutions often have larger file sizes), and then return to the higher resolution for finishing.

This way of thinking is known as an offline/online workflow, and we will talk much more about it. Originally, it came about in the early days of nonlinear editing, before computers were robust enough to handle full-resolution footage digitally. The solution was to edit with low-resolution proxies or “offline” clips, and then assemble the final piece in a traditional tape-to-tape room based on the decisions that were made nonlinearly.

Final Cut Pro has added a lot more flexibility to this method. Resolution independence means that an HD piece can be rough cut at DV resolution, then reconformed to HD, or that a ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Authors

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- How to Get the Most From This Book

- Part 1: Final Cut Pro in Context

- Part 2: Roles, Technologies, and Techniques

- Part 3: Real-World Work.ows

- In Between …

- Index