![]()

CHAPTER 1

MAKING WAVES

On June 27, 1975, 50 miles off the coast of California, the Soviet whaling ship the Vlastny, armed with a 90-millimeter cannon loaded with a 160-pound exploding grenade harpoon, departs from the factory ship Dalniy Vostok in pursuit of sperm whales. Unlike any previous hunt, though, the Vlastny finds itself pursued by six Greenpeace activists in three Zodiacs (inflatable rubber dinghies) “armed” with one film camera and intent on confronting the whaler and intervening on behalf of the whales. One Zodiac, bobbing in and out of sight on the rough swells, manages to position itself between the harpoon ship and the nearest whale. The two activists in the Zodiac are betting that the whalers will not risk killing humans in order to kill whales. They lose. Without warning, the whalers fire over the heads of the activists, striking the whale. The steel harpoon cable slashes into the water less than 5 feet from the Zodiac.

Though Greenpeace’s direct action failed in its most immediate goal of saving the whale, it succeeded as an image event.1 Greenpeace caught the confrontation on film, and it became the image seen around the world, shown by CBS, ABC, and NBC News and on other news shows spanning the globe. For Robert Hunter, director of Greenpeace at the time and one of the activists in the path of the harpoon, Greenpeace had succeeded in launching a “mind bomb,” an image event that explodes “in the public’s consciousness to transform the way people view their world” (1971, p. 22). The consequence of this image event for Greenpeace was, as Hunter observed, that “with the single act of filming ourselves in front of the harpoon, we had entered the mass consciousness of modern America” (1979, p. 231).

Two Greenpeace activists in an inflatable Zodiac confront a Soviet whaling fleet. In capturing this initial protest on video and then disseminating it to news organizations, Greenpeace succeeded in igniting international indignation, jumpstarting the campaign to ban whaling, and establishing themselves as a force in the international public sphere.

This opening act of Greenpeace’s “Save the Whales” campaign echoed Greenpeace’s founding act 4 years earlier, which also failed as a direct action but succeeded as an image event. Expatriate Americans and Canadians upset with the U.S. nuclear testing program chartered two boats to travel to Amchitka, one of the Aleutian Islands, in order to bear witness to and protest a scheduled underground nuclear explosion there. Underfunded and poorly equipped, the Greenpeacers were over 1,000 thousand miles away when the test took place. Though Greenpeace failed to stop that blast, the resulting publicity (two Canadian journalists were also Greenpeace crew members) generated a groundswell of protest and forced the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission to announce 4 months later that it was ending testing in the Aleutians for “political and other reasons” and returning Amchitka to its use as a bird and sea otter refuge (Brown and May, 1991, p. 15). Though at the time the Greenpeace crew members were unaware that “while a battle had been lost, the war had been won” (Hunter, 1979, p. 113), they have since learned that with image events it “is not whether they immediately stop the evil—they seldom do. Success comes in reducing a complex set of issues to symbols that break people’s comfortable equilibrium, get them asking whether there are better ways to do things” (Veteran Greenpeace campaigner, quoted in Horton, 1991, p. 108).

Since 1971 Greenpeace has performed thousands of image events in support of issues ranging from whaling, to nuclear testing, to the siting of hazardous waste incinerators. Greenpeace activists have steered rubber rafts between whaling ships and whales, chained themselves to harpoons, spray-painted baby harp seals to render their pelts worthless, plugged waste discharge pipes, simultaneously hung banners from smokestacks in eight European countries in order to create a composite photograph that would spell out “STOP” twice, dressed as penguins to protest development of Antarctica, delivered a dead seal to 10 Downing Street (home of the British prime minister), and used drift nets to spell out “Ban Drift Nets Now” on the Mall in Washington, DC (Brown and May, 1991). The effects have been stunning. Greenpeace has parlayed the practice of creating image events as their primary form of rhetorical activity into the largest environmental organization in the world, reaching heights of almost five million members and gross revenues of $ 160 million (Horton, 1991, p. 44).

These tactical image events have driven numerous successful campaigns that have resulted in the banning of commercial whaling, harvesting of baby harp seals, and ocean dumping of nuclear wastes; the establishment of a moratorium in Antarctica on mineral and oil exploration and their extraction; the blocking of numerous garbage and hazardous waste incinerators; the requirement of turtle excluder devices on shrimp nets; the banning of the disposal of plastics at sea by the United States; and much more.

The vehemence of the counterresponse also testifies to the power of Greenpeace’s image events. French commandos boarded a Greenpeace vessel and severely beat a Greenpeace crew member. The French government, exasperated by Greenpeace’s campaign against its nuclear testing in the South Pacific, had secret agents blow up and sink the Greenpeace flagship, the Rainbow Warrior, a terroristic act that resulted in the murder of Greenpeace member Fernando Pereira. The U.S. Navy rammed a Greenpeace ship seeking to block a Trident submarine. Greenpeace director of toxics research Pat Costner’s house was burned down by arsonists.

In addition to its practical achievements, Greenpeace is also highly significant as a model that demonstrates how to exploit the immense possibilities of television for radical change. Indeed, Greenpeace is arguably the first group working for social change, and certainly the first environmental group, whose primary rhetorical activity is the staging of image events for mass media dissemination.2 Although media tactics are not new, Greenpeace is the first group both to explore fully and trust in the progressive potential of television, reflecting their Canadian lineage and the influence of Marshall McLuhan on key original members. For example, before joining Greenpeace in 1971, Hunter called McLuhan “our greatest prophet” (1971, p. 221). Paul Watson, an original member of Greenpeace and later founder of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, explains, “When we set up Greenpeace it was because we wanted a small group of action-oriented people who could get into the field and, using these McLuhanist principles (for attracting media attention), make an issue controversial and publicize it and get to the root of the problem” (quoted in Scarce, 1990, p. 101). Traditionally, radical activists on the left have been and continue to be wary if not contemptuous of mass media (e.g., Angus and Jhally, 1989b; McLaughlin, 1993) in favor of fetishizing immediacy (e.g., Baudrillard, 1981). This attitude is akin to what McLuhan describes as the “bulldog opacity” of literate people in response to the new technologies of mass media: “literate man3 is not only numb and vague in the presence of film or photo [or video], but he intensifies his ineptness by a defensive arrogance and condescension to ‘pop kulch’ and ‘mass entertainment’” (1964, p. 175). Early Greenpeace members took to heart McLuhan’s aphorism “the medium is the message” and accepted McLuhan’s challenge not to cower in their ivory towers bemoaning change but to plunge into the vortex of electric technology in order to understand it and dictate the new environment, to “turn ivory tower into control tower” (Hunter, 1971, p. 221). The early members of Greenpeace thought of themselves as media artists and revolutionaries, in line with McLuhan’s contention that the “artist is the man in any field, scientific or humanistic, who grasps the implications of his actions and of new knowledge in his own time” (1964, p. 71).

In a book written shortly before Greenpeace’s first image event, original member and early director Hunter argued that all revolutions are attempts to change the consciousness of the “enemy,” and pointed out that in the past the “only medium through which a revolution could communicate itself was armed struggle.” Today, however, the mass media provide a delivery system for strafing the population with mind bombs (Hunter, 1971, pp. 215–224). This philosophy of mass media has translated into a practice of staging image events based on the argument that “when you do an action it goes through the camera and into the minds of millions of people. The things that were previously out of mind now become commonplace. Therefore, you use the media as a weapon” (Hunter, quoted by Watson, in Scarce, 1990, p. 104). Fellow original Greenpeace member Watson elaborates, “The more dramatic you can make it, the more controversial it is, the more publicity you will get. … The drama translates into exposure. Then you tie the message into that exposure and fire it into the brains of millions of people in the process” (quoted in Scarce, 1990, p. 104).

Clearly, these early Greenpeace activists’ theoretical insights on media could stand further development. They have a narrow conception of media that McLuhan would have frowned upon, they ignore a host of alternatives to armed struggle, and they adopt a causal model of media influence reminiscent of the discredited hypodermic needle model. Nonetheless, although theoretically a bit simplistic, in practice Greenpeace activists are sophisticated media artists who have been so successful that their artistry has been imitated by a legion of admiring radical environmental groups.

Guerrilla Imagefare in the Woods

To protest logging on public lands in North Kalmiopsis, Oregon, home to “the most diverse coniferous forest on Earth” (Scarce, 1990, p. 67), Valerie Wade scales a yarder (a truck with a huge pole that uses cables to drag logs up and down steep slopes), perches precariously 90 feet up, and hangs a banner reading “From Heritage to Sawdust.” To save old-growth forest, an Earth First! activist sits on a platform suspended 100 feet up in a giant Douglas fir, dwarfed by the trunk even at that height. Deep in the woods, a blue-capped, smiling, bearded head pokes up out of a logging road; the rest of the person is buried in the road. This attempt to stop logging by blockading the road adds new depth to the terms “passive resistance” and “active noncooperation.” Such immobility, while making the tactic more effective, also renders the immobile activist more vulnerable to angry loggers and law enforcement officials.

On the 1981 spring equinox members of Earth First! unfurled a 300-foot-long plastic ribbon down the Glen Canyon Dam in order to simulate a crack in the dam, thus symbolically cracking this “monument to progress” clotting the Colorado River. With this image event (inspired by the Edward Abbey novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang), Earth First!, a radical, no-compromise environmental group founded a year earlier by five disgruntled mainstream environmentalists during a beer-besotted camping trip in the Pinacate Desert, debuted in the public consciousness. Since then, while Earth First! has deployed an array of tactics, most notably “ecotage” (ecological sabotage) or “monkeywrenching,” in defense of natural ecosystems, image events have been their central rhetorical activity as they attempt to change the way people think about and act toward nature.4

In their efforts to put onto the public agenda issues such as clear-cutting of old-growth forests, overgrazing by cattle on public lands, depradations of oil and mineral companies on public lands, loss of biodiversity, and the general ravaging of wilderness, Earth First! activists have resorted to sitting in trees, blockading roads with their bodies, chaining themselves to logging equipment, and dressing in animal costumes at public hearings. Although these direct actions often fail in terms of accomplishing their immediate goals, their effectiveness as image events can be partially measured by the emergence of clear-cutting, old-growth forests, spotted owls, cattle grazing, and the 1872 mining law as hot-button political issues that national politicians are forced to respond to. For example, George Bush runs for office as the “environmental president”; AI Gore is picked as the Democratic vice-presidential candidate in part because of his “green” credentials; President Clinton holds a “Forest Summit” in the Northwest over old-growth forest and the spotted owl; Congress of late perennially tries to reform the 1872 mining law; and the Clinton Administration initially advocates raising grazing fees on public lands (but later backs down in a move that signals to Clinton’s political opposition that he can be browbeaten).

Earth First!, like Greenpeace before them, understands that the significance of direct actions is in their function as image events in the larger arena of public discourse. As philosopher and deep ecologist Bill Devall explains, direct action “is aimed at a larger audience, and the action should always be interpreted by the activists; Smart and creative communication of the message is as important as the action itself” (quoted in Manes, 1990, p. 170). Although designed to flag media attention and generate publicity, image events are more than just a means of getting on television. They are crystallized philosophical fragments, mind bombs, that work to expand “the universe of thinkable thoughts” (Manes, 1990, p. 77).

Because Earth First!’s rhetoric and goals fundamentally challenge the discourse of industrialism and progress, their power is perhaps most evident in the vehemence of the counterrhetoric and backlash they have provoked. Newspapers have labeled Earth First!ers “tree slime,” “human vermin,” and the “eco-equivalent of neo-Nazi skinheads” (quoted in Short, 1991, p. 181). In the U.S. Congress Senator James McClure of Idaho compared Earth First! to “hostage-takers and kidnappers” (Short, 1991, p. 185) and added a provision to an anti-drug bill making tree-spiking (a form of ecotage) a federal crime. At a 1989 campaign rally, Representative Ron Marlenee (R-MT) advised loggers to “spike an Earth First!er” (quoted in Lancaster, 1991, p. B1). The House, under cover of the Contract with America, passed legislation designed to gut environmental protection laws and deregulate industry (Helvarg, 1995a). Idaho Governor Cecil Andrus, who called Earth First! protestors “just a bunch of kooks,” signed a “trespass” law that makes it a felony to interfere with logging activities, thereby equating nonviolent direct actions and civil disobedience (image events) with terrorism (Cockburn, 1995a, 1995b). The U.S. Forest Service has employed heavily armed “pot commandos” (law enforcement agents ostensibly cracking down on marijuana growers) to arrest protesters and has issued closure orders designed to prevent environmental activists from entering public lands where clear-cutting is going on, thus effectively preventing protests and silencing dissent. The FBI has used wiretaps and infiltrators in a $2 million surveillance operation against Earth First! known as Thermcon, which resulted in the arrests of a number of Earth First!ers, including cofounder Dave Foreman. As FBI infiltrator Michael Fain unwittingly revealed when he accidentally bugged his own conversation with two other agents, the arrests were political: “[Foreman] isn’t really the guy we need to pop—I mean in terms of actual perpetrator. This is the guy we need to pop to send a message” (Manes, 1990, pp. 195–197). Evidently, even the FBI thinks in terms of image events.

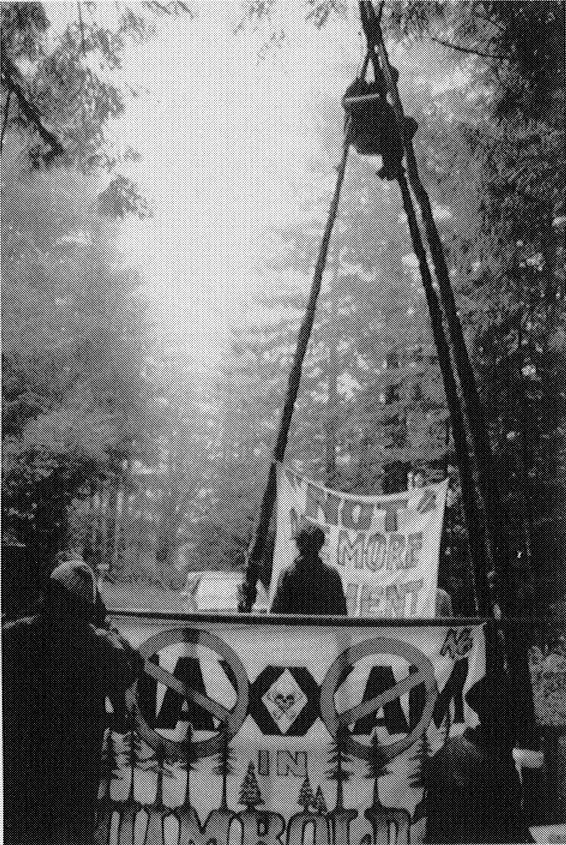

Earth First! activists use a “tri-pod” and gate “lock-down” to block a logging road. Their signs read “NOT ONE MORE ANCIENT TREE” and “NO MAXXAM IN HUMBOLDT COUNTY”.

Corporations used to exploiting resources on public lands with impunity have hired private investigators to spy on environmentalists and security firms to infiltrate Earth First! They have even ringed controversial logging sites on public lands with electronic motion detectors in order to monitor the movements of people in the forests, effectively transforming public lands into private security zones (Manes, 1990, p. 214). Also, corporations have filed strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) against activists in efforts to silence them.

The backlash has also become physically violent, as workers, security personnel, law enforcement officials, and members of a corporate-sponsored grassroots anti-environmental movement known as Wise Use have attacked environmentalists (though Wise Use is against environmentalism in toto, they particularly target Earth First! and environmental justice activists). Besides being subjected to vandalism and death threats, hundreds of activists have suffered serious violence. Dave Foreman was run over at a blockade. Earth First!er Lisa Brown, who had locked her neck to a timber loader with a bicycle lock, was shot at by a security guard. Other activists have been beaten and tree-sitters have had the trees they were sitting in cut down. On September 17, 1998 David Chain, an Earth First!er, was crushed to death by a redwood when an irate Pacific Lumber logger continued felling trees despite the presence of Earth First! protesters (Goodell, 1999).

In 1988 Wise Use declared a “holy war against the new pagans who worship trees and sacrifice people” (Helvarg, 1994b, p. 648). Wise Use founder Ron Arnold decl...