CHAPTER 2

HERE IN THIS MAGIC WOOD

Behold! This is the announcement of much to do:

To invoke Tu, Tu of the outer space,

Tu, eater of people.

Streamer! Streamer for us, streamer for the gods,

Streamer that protects the back, that protects the front.

The interior was void: the interior was empty.

Let fertility appear and spread to the hills.

Grant the smell of food, a portion of fatness,

A breeze that calls for fermentation.

Polynesian first fruits feast

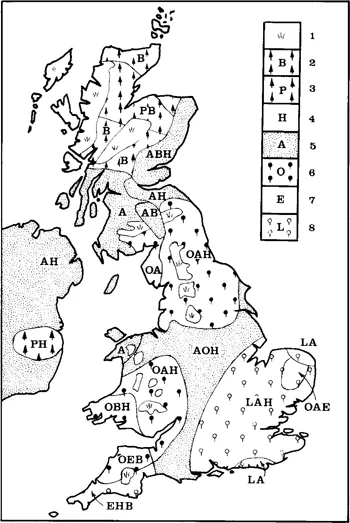

When we reconstruct in our mind’s eye the virgin forest that stretched from one end of Britain to the other at the beginning of the neolithic, we have a measure of the magnitude of the neolithic enterprise. Little else, after all, could be done until substantial areas of the forest had been cleared. When the great forest developed, Britain was a moister and a warmer land, warmer than today by two degrees Celsius. The temperature had risen gradually since the end of the Ice Age some two thousand years before and cold-tolerant trees like the pine were in retreat, making way for warmth-loving deciduous species. The pine had virtually disappeared in England and only remained as a major element in the forests of the eastern Scottish Highlands, where as many as 40 per cent of the trees were pines. The birch too was in retreat and only made an important constituent of the forests in the northern half of Britain (Figure 1).

Huge tracts were mantled by deciduous forest and there were few open spaces to attract colonists. Above 750 metres there were patches of high, montane grassland; unstable land surfaces like screes were without vegetation; limestone areas such as Upper Teesdale were sparsely vegetated with low-growing herbs. Apart from these limited and unattractive areas, the only two kinds of open habitat remaining were the coastline and the lower slopes of the valley sides. These ecological boundaries were magnets to pioneer settlers as little work was needed to clear sites for houses and gardens and on each side there were contrasting habitats offering a variety of foodstuffs.

There were some pure oakwoods but in most places the forest was a complex mosaic of deciduous trees, with oaks, elms, alders and limes making a canopy and hazels composing the understorey. Limes, which are warmth-loving, were confined to southern Britain, where they accounted for as many as one-tenth of the forest trees.

1 The forest: predominant tree species at the beginning of the neolithic.

1 montane grassland and open shrubland

2 birch

3 pine

4 hazel

5 alder

6 oak

7 elm

8 lime.

Where two or three letters are shown, they are arranged in order of precedence, the first indicating the dominant species

As the pioneers trekked through the forest searching for suitable areas to clear, they would have seen significant variations from region to region. The oakwoods of the Midland claylands were much denser than the oak-hazel woodlands of the chalklands of Dorset. Pine-birch forests covered the north-eastern highlands of Scotland. On the exposed, windswept, salt-sprayed islands of the far north there was a shrubland of birch, willow and hazel with a ling field layer; Orkney seems never to have held a true woodland cover, although isolated yews, oaks and hawthorns managed to gain a foothold. By contrast, the oak-alder forests of East Anglia had many elms and birches in it, as well as a few limes and pines, making a dense, closed forest with a poor field layer under its deep shade.

In the early neolithic, the Fens were dry enough to support an oak forest, but as the ground became more waterlogged the vegetation thinned out into a tract of sedge fen with a light canopy of alder, birch and sallow. Similar vegetation was found in the Somerset Levels, the lowlands flanking the Humber and Firth of Forth, and numerous other ill-drained sites.

In the south-west there was mixed oak forest everywhere except on the high moors. There, on the flat summits, blanket-peat formed, with only cotton-grass and sphagnum moss growing. Blanket-peat formed in the other mountain areas too, wherever there were level surfaces higher than about 360 metres. On sloping ground the forest went on up to at least 750 metres and at the outset even the flatter raised bog areas were covered by alderwoods.

Plate 1 The primeval oakwood. Much of Britain looked like this at the beginning of the neolithic

In spite of all these variations, the early neolithic forest was more continuous and more homogeneous than it was ever to be in later times. Although there were local changes in its composition and quite important differences in density, the forest when seen from a high mountain top would have appeared uniform and virtually continuous, with far less distinction between highland and lowland zones than we can see today. It is said that a squirrel could have crossed the country from one side to the other without ever setting foot on the ground, so continuous was the canopy. The forest smothered Britain like a vast green sea; as it existed in 5000 BC it presented a formidable challenge to the earliest neolithic farming communities.

FARMING IN THE PIONEER PHASE

When the first settlers arrived in about 4700 BC, they chose the easier, open sites. In the following phase of prospection, they assessed and then exploited the environment with a blend of mesolithic and neolithic techniques. The open, ecological boundary zones offered wide possibilities for hunting, fowling, fishing and gathering. At the same time, small garden-like plots were opened up in the lighter woodland for cultivation. A temporary clearance was made by felling and burning, followed by a few years of crop cultivation. After that the soil was exhausted and crop yields sank so low that the forest was allowed to regenerate. As each clearing was abandoned, it was overgrown first by grasses and weeds, then by bracken and small trees such as birch or hazel, and finally by tall trees. The sequence was repeated endlessly as the pioneers moved on through the forest to make one new clearing after another.

The pioneer phase as we see it here is close to the traditional view of neolithic farming as a whole; small, primitive groups scratching a precarious living in clearings in a vast primeval forest. The land clearance in the lowlands of Cumbria involved several successive temporary clearance episodes, reminiscent of the ‘slash-and-burn’ techniques of present-day tropical cultivators. Similarly, at Llyn Mire in the Wye valley there were at least two phases of cereal cultivation followed by soil exhaustion and woodland regeneration in only twenty years.

THE EARLY NEOLITHIC

During the next phase, beginning in about 4300 BC and continuing until about 3500 BC, forest clearance was on a larger scale and of longer duration. A Danish experiment in forest clearance followed by cereal cultivation showed that the yield of emmer wheat fell rapidly; by the third year, cultivation was no longer worthwhile. This suggests that the pioneer clearance episodes were very short. The later clearances were more substantial. Several places in East Anglia, such as Hockham Mere and Seamere, give evidence of a landscape kept open for up to three hundred years. At Hockham Mere where the soils are light and friable the initial clearance was in 3770 BC: by 3450 BC the forest had closed in again to remain untouched, apparently, for another four hundred years. The forest covering the Wessex chalklands was opened up for cultivation in much the same way. The pollen and snail record at several Wessex monuments shows that the forest was cleared and then cultivated; after that there was often a change of land use from cultivation to pasture. The same record of clearance is repeated at site after site and by 3500 BC large tracts of chalk hill country were open.

The clearance may have been done with stone axes mounted in wooden hafts. We know from modern experiments in Denmark that three men can clear 500 square metres of forest in four hours using polished flint axes; working for a week, they can make a substantial clearing of about a hectare. Even so, a good deal of sweated labour is involved and the neolithic farmers may not have been in such a hurry. Tree-ringing could have been used instead; left for a year until they had died and dried out, the trees could then have been destroyed by firing. Alternatively, or in addition, livestock could be used. If turned into a woodland in sufficient numbers, cattle can destroy it by trampling the seedlings. This method would take much longer, as it would only prevent the forest from regenerating: the existing trees would be relatively undamaged. It is possible that the man-made clearings gradually expanded because of this type of interference.

We know that fire was used to clear some sites, such as the pinewoods of Great Langdale in Cumbria and Ben Eighe. In a gravel pit at Ecton in Northamptonshire I have seen charred tree trunks 30 centimetres and more in diameter preserved horizontally in neolithic peat layers. The blackened, crazed tree trunks are clear proof of forest clearance by fire on the gravel floodplain of the River Nene; the clearance was right beside a neolithic occupation site and almost certainly contemporary with it.

The chalk uplands of southern and eastern England were among the first areas to attract farmers, because the soils were light and easy to manage with simple implements and also because they were loessic and very fertile. Much has been made in the past of the chalklands as a focus for neolithic agriculture, but a wide range of landscapes was brought into the economy. The calcareous uplands of the Cotswolds were used for pasture and cultivation. The heavy soils of the lowlands round Bath produced wheat. In Wales there was pastoral activity on upland sites while cereals were grown in the Wye valley. The lowlands surrounding the Lake District produced cereals while the forested lakeland valleys were used for collecting leaves for fodder, and temporary clearance of oakwoods, e.g. in Ennerdale between 4000 and 3400 BC, may have provided summer grazing. Why the higher pine and birch woods in the Great Langdale area were cleared by firing in 4600 and 3460 BC is not at all clear. The gritstone moors of the Pennines were cleared in a small way for summer grazing on the Nidderdale Moors near Ripon and also to the west of Sheffield, presumably by transhumant farmers based on the lowlands to the east.

Most of the farmers were based in the lowlands. Detailed studies of Orkney and Penwith show that at one site after another the megalithic tombs stand just above and overlook a patch of fertile arable land. Even though commanding hillside and hilltop sites were often chosen for the monuments, they marked the upper margins of the farming territory, the wilderness edge.

There was a flurry of activity in the Midlands too. Far from remaining a huge and intractable expanse of continuous oak-alder forest, the Midlands had a substantial farming population exploiting the easily managed and fertile soils of the terraces along the sides of the major valleys. In East Anglia, away from the western chalklands, the farmers again focussed on the low, flat, fertile terrain of the river terraces, such as Eaton Heath on a low terrace of the River Yare. The claylands of East Anglia seem to have been left alone; Buckenham Mere, only 10 miles east of Hockham Mere but on heavy clay, was left forested until the bronze age.

Large areas of forest were left untouched right through the neolithic in North Yorkshire, East Durham, the claylands of East Anglia and the Midlands, the New Forest and probably the Vales of Kent and Sussex. The abundance of game for hunting shows that forest was widespread. Yet by 4000 BC there were already countless small clearings, many of them temporary but an increasing number permanent. By 3500 BC much of the chalkland of southern and eastern England was open, while much of the rest of Britain was a mosaic of clearings for cultivation and pasture, open woodland, closed forest, montane grassland, fen and raised bog.

The apparent contrast between south and north is slightly puzzling. Far more land remained open, though not necessarily under cultivation, in southern Britain than in the north. It may be that the chalkland pastures were easy to turn over to sheep and cattle, whose grazing would have maintained a permanent grassland over wide areas. But why was this not happening, as far as we can judge, in northern Britain? Maybe the population density and thus the food requirements were greater in the south. Maybe the gently undulating plateaux that make up most of the chalk country made better livestock ranching terrain than anything that could be found in the highland zone. More likely it was both, a result of population pressure and natural advantages inherent in the landscape.

Generally, farmers did not clear level ground as this could raise the water table and lead to the formation of bogs. This shows an awareness of environmental processes surprising at such an early date. Although some have argued that neolithic people were partly responsible for the formation of raised bogs, there is no real evidence that they were. In some areas peat was forming in the uplands well before the neolithic, whilst in Northern Ireland it was developing in the bronze age; it really seems unrelated to culture.

Clearance in northern England was not so extensive as in southern England, and here too there was a concentration on the lighter calcareous soils. In East Yorkshire, barrows and settlements cluster on the alkaline soils of the Tabular Hills and Yorkshire Wolds, avoiding the clay and sandstone areas. In Cumbria, clearance focussed on the coastal lowlands, while the mountainous interior was left largely uncleared, though used for fodder-gathering, hunting and axe factories.

As yet there is little evidence for clearance in Scotland. At Pitnacree in the Tay valley, the forest seems to have been cleared when the barrow was built, in 4080 BC. The same thing happened at Dalladies in Kincardineshire five hundred years later. The distribution of the Scottish tombs, very close to the present upper limit of arable farming, suggests once again that farmers were selecting the warmer and more fertile lower slopes. The idea that chambered tombs and earthen long barrows should command the farmed territory from its upper boundary seems to have been widespread.

On Orkney, land clearance phases of the pioneer type did not occur; trees were never dominant and once cleared the islands seem to have remained open. Farmers selected the lower slopes for agriculture, areas coinciding broadly with those in use at the present day for arable farming. On both Rousay and Mainland Orkney, each farming territory was overlooked by its own territorial chambered tomb standing on slightly higher ground.

CROPS AND LIVESTOCK

In some areas, pasture for livestock grazing was established very early on, perhaps immediately after clearance, but the farmers’ first priority was to grow cereals, which are known from as early as 4200 BC at Hembury in Devon. The main cereals were emmer wheat, naked six-row barley and hulled six-row barley: all three were common in neolithic Europe generally. Some farmers were growing einkorn wheat and club wheat, and their fields were dotted with knotweed, chickweed, bindweed and burdock. Flax may have been grown for its seeds, which could be pressed for linseed oil, or its fibres, which could be used to make linen. So far, no trace has been found of any vegetables and it may be that this area of the diet was filled by gathered food such as blackberries, barberries, sloes, crab apples, haws and hazel nuts.

Fields on the lower slopes were generally used for extended periods of cultivation, whilst those at higher altitudes deteriorated quite quickly and sustained only short-term cultivation. The Danish pioneer clearance experiment showed that only ...