eBook - ePub

Living In A Learning Society

Life-Histories, Identities And Education

- 125 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Living In A Learning Society

Life-Histories, Identities And Education

About this book

This text discusses the meaning of education through an examination of life paths, identities and significant learning experiences. Looking at education over three generations of war and scant education; of structural change and increasing educational opportunities; and of social well-being and wide educational choice the book examines a variety of questions.; The book demonstrates how the synthesis of social and cultural interpretations of education forms four groups: resource, status, conformity and individualism. The implications to education policy in late-modern or postmodern society are also discussed.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Living In A Learning Society by Ari Antikainen,Jarmo Houtsonen,Juha Kauppila,Hannu Huotelin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Bildung & Bildung Allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

BildungSubtopic

Bildung Allgemein1 How to Study Peoples’ Lives?

Ethical Ideals

Anna’s letter to our research group, quoted on the cover page, tells of the mutual relationship between the researcher and the person supplying the data in interview situations. It is seen by Martin Hammersley and Paul Atkinson (1979, p. 116) as a ‘research bargain’, and by Ivor Goodson (1991, p. 148; 1992) as ‘trading’ between the researcher and the participant or between the life history ‘taker’ and the life history ‘giver’. As Lynda Measor and Patricia Sikes put it:

The research bargain is a social construction, the result of assessments by each side of what the other has to give and what they are prepared to offer in return for these things (Hammersley and Atkinson, 1979, p. 120). . . . Respondents are not fearful victims who open their lives and souls because they are told or asked to. People have boundaries and strategies to protect themselves in research situations. (1992, p. 230)

Norman Denzin makes his stance on the ethical code of the life history researcher very clear:

. . . we must remember that our primary obligation is always to the people we study, not to our project or to a larger discipline. The lives and stories that we hear and study are given to us under a promise, that promise being that we protect those who have shared with us. And, in return, this sharing will allow us to write life documents that speak to the human dignity, the suffering, the hopes, the dreams, the lives gained, and the lives lost by the people we study. These documents will become testimonies to the ability of the human being to endure, to prevail, and to triumph over the structural forces that threaten at any moment to annihilate all of us. (1989, p. 83)

The study in this book deals with the place and meaning of education and learning in people’s lives. The data was collected at a time when governments, corporations and bureaucrats were planning new systems of lifetime learning for people without listening to and hearing people’s own voices. More recent programmes of critical pedagogy seem to describe the research bargain beyond our study very well. For example, five of six specific features of critical pedagogy presented by David Livingstone are:

First, critical scholars must thoroughly appreciate that the prime task of educational scholarship is not merely to convey naturalistic understanding of educational practices but, as Walter Feinberg (1983, p. 153) puts it: ‘. . . to reflectively understand these relationships as social constructions with historical antecedents and thereby to initiate an awareness that these patterns are objects of choice and possible candidates for change. Thus educational scholarship adds a consciously critical dimension to the social activity of education.’ Secondly, such research can only be adequately accomplished through identifying discrepancies between dominant versions of reality promulgated in formal institutions and the lived experience of subordinate groups in relation to such institutions. Thirdly, such identification requires scholars to attempt to take the vantage point of the subordinated, and this vantage point can only be sustained in contemporary critical inquiry if scholars remain engaged in collective dialogue with people more fully immersed in oppressive social relationships. Fourthly, the dialogue of critical pedagogy should not be restricted to narrow educational concerns focused only on the schools alone or including mass media and family spheres, but should facilitate popular efforts to make sense of the entirety of everyday life in relation to practice. Fifthly, it is through subordinated peoples’ own discussion, growing self-consciousness and informed action in relation to their social reality — their appropriation of cultural power — that more no-elitist democratic forms of education and other societal institutions are most likely to be generated and sustained. (1987, p. 10)

Methodological Restrictions

Life-history studies is an emerging field in education now. It is vital, therefore, to remember that ‘major shifts (in methodology) are more likely to arise from changes in political and theoretical preoccupation induced by contemporary social events than from discovery of new sources or methods’ (Popular Memory Group quoted in Goodson, 1992, p. 248). In the 1970s, interactionist and ethnomethodological methods emerged in the shadow of predominantly quantitative functionalist and structuralist studies both in the mainstream and in Marxism. The situation most commonly focused on in interactionist and ethnomethodological studies was school lessons; biography was still neglected (Goodson, 1981, p. 67). After the destruction of such meta-stories as Enlightenment and Marxism (Lyotard, 1984), the field of life history has expanded.

Lives and their experiences are represented in stories. They are like pictures that have been painted over, and, when paint is scraped off an old picture, something new becomes visible. What is new is what was previously covered up. A life and the stories about it have the qualities of pentimento. Something new is always coming into sight, displacing what was previously certain and seen. There is no truth in the painting of a life, only multiple images and traces of what has been, what could have been, and what now is. (Denzin, 1989, p. 81)

From his structural position, Pierre Bourdieu (1987) sees the biographical project as an illusion (Roos, 1987a), for any coherence that a life has is imposed by the larger culture, by the researcher, and by the subject’s belief that his or her life should have a coherence (Denzin, 1989, p. 61). In his response to Bourdieu’s critique, Denzin states:

The point to make is not whether biographical coherence is an illusion or a reality. Rather, what must be established is how individuals give coherence to their lives when they write or talk self-autobiographies. The sources of this coherence, the narratives that lie behind them, and the larger ideologies that structure them must be uncovered. (1989, p. 62)

From a postmodern perspective, the narrator’s notion of a ‘life’ can be seen as just a textual product. But, could the ‘life’ be rescued from the text by any means? Maggie McLure and Ian Stronach conclude:

A qualifying point needs to be registered. We have argued that authenticity, validity, and recognition are textual accomplishments — that they are not ‘really’ methodological — stressing the ‘tyranny of the text’. This raises the question of whether methodological questions are reducible to textual ones. There are two answers. For the reader; texts can only be authenticated in themselves: the reader has no other resource than the persuasiveness of the text. But for the researcher; the problem of the interrelationship of methodology and the text remains important. . . We do not seek to dismiss methodology but rather to bring its textual properties to light — to ask, what sorts of stories are implicated in a particular methodology and what sorts of stories are suppressed or made un-tellable? (1993, p. 378)

Reflecting on our own data, we wondered if the stories of life and learning were biased toward positive and coherent outcomes. Therefore at the end of the thematic interview we asked the interviewee to describe his or her most negative educational and learning experience. Thus, we try to get at least two kinds of stories. There are, however, researchers who acknowledge poststructuralism and the power of the text but believe that autobiography is a referential genre where truth and reality are seen from the unique and concrete point of the narrator who is simultaneously a narrator and sees her- or himself as a narrator (Eakin, 1992; Roos, 1994). One could argue that we more or less share this view but, in fact, we have tried to include intertextuality in all our analysis, as is clearly presented in chapter 3.

Ivor Goodson makes a clear distinction between life-story and life-history.

. . . life studies should, where possible, provide not only a ‘a narrative of action!, but also a history or genealogy of context. I say this in full knowledge that this opens up substantial dangers of changing the relationship between life story giver’ and ‘research taker’ and of tilting the balance of the relationship further towards the academy. (1992, p. 240)

The next step is a collaborative intertextual approach where participant and researcher can collaborate in investigating not only the stories of lives but also the contexts of lives (Goodson, ibid., p. 244).1 Ivor Goodson (1995) argues, however, that in the context of the cultural logic of postmodernity and redundancy of stories a specific empowerment can go hand in hand with overall social control.

In this study, a context-sensitive social constructionist approach is applied. Studying the rapidly modernized Finnish society as a specific example of Nordic societies, educational generations form the first context of the life histories. The contexts of significant learning experiences are negotiated with the interviewees, but the study is still far from ‘collaborative intertextual research’. The data consists of narrative and thematic interviews, that both cross and are complementary to each other.

In chapter 2 the concepts of learning society and lifelong learning are presented in the context of a swiftly changing Finnish society with expanding education opportunities. In chapter 3, Hannu Huotelin continues the methodological enquiry started in this introduction. He argues that biographical method or life history offers ‘a perspective to the mosaic of reality’. In chapter 4, Juha Kauppila and Hannu Huotelin present their interpretation of three contemporary educational generations in Finland. The analysis is close to a grounded theory approach but is conceptualized and contextualized by the Mannheimian concept of generation. These three generations are common to all Western societies that participated in the Second World War, and constructed the welfare state and consumer society. In chapter 5, Jarmo Houtsonen asks what kind of identities education produces, both in mainstream and in minority culture. The case of Manta, an 80-year-old Sami woman in Lapland who lives at the crossroad of two cultures, is analysed thoroughly. The approach applied has certain Meadian and phenomenological influences, but the concept of identity is drawn from Erving Goffman. In chapter 6, Ari Antikainen searches for the significant learning experiences in life stories. The ideas of transformation, and transformation by significant events, have been deeply entrenched in Western thought at least since Augustine (Denzin, 1989, p. 22). These ideas lead the analysis to subjectivization and empowerment. In the two concluding discussion chapters the cultural patterns of modernization, produced or co-produced by education and the emerging new, brave, but still class, gender and ‘race’ biased learning society, are under scrutinity. Thus we attempt to situate peoples’ learning experiences in the context of long-term societal learning processes. Social learning processes occur typically in the condition of problem accumulation. In the middle of a global problem accumulation we could hear a young scholar’s voice:

We ascribe existential value to human experience — it is experience that produces the coding of reality. Man’s [human] consciousness and her or his sociability are based on experience and establish a time-resistant continuity of meaning, which originates from processes of suffering. The social transformations of human actions, which are based on social learning processes, are a function of the reduction of suffering. It is only with the experience of increased suffering that man’s [human] willingness for social cooperation grows, a willingness which is usually suppressed for fear of contact. (Ternyik, 1987, p. 17)2

2 The Meaning of Education

What is the Meaning of Education?

In the research project ‘In Search of the Meaning of Education’, we are studying the meaning of education and learning in the lives of people who live in a swiftly changing society with expanding education and learning opportunities — in our case in Finland (Antikainen, 1991). In addition to formal education, we are interested in adult education and other less formal ways of acquiring knowledge and skills. Our conception of meaning refers both to our method and to our theory.

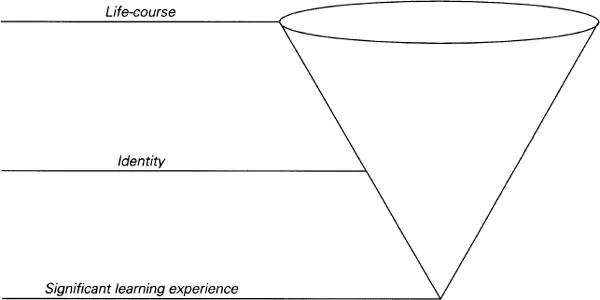

We are investigating intersubjective social reality by means of a qualitative logic, not of statistical representativeness. We are using a life-history approach with a life-story interview and a thematic interview as our methods (Huotelin, 1992; Thomas and Znaniecki, 1918–1920; Denzin, 1989). According to our theory, the meaning of education can be analysed at three levels, as indicated by the following three questions and illustrated in Figure 2.1:

- How do people use education in constructing their life-courses?

- What do educational and learning experiences mean in the production and formation of individual and group identity?

- Our project’s very first life-story was that of a 66-year-old woman, Anna. We noted that her life organized itself as a series of key learning experiences (Antikainen, 1993). These experiences — which in the light of superficial examination seem to have organized the narrator’s life-course or to have changed or strengthened her identity — we have called significant learning experiences. We can thus ask what sort of significant learning experiences people have in the different stages of their lives? Do those experiences originate in school, work, adult study or leisure-time pursuits? What is the substance, form and social context of significant learning experiences?

Figure 2.1: Key concepts: life course, identity and significant learning experiences

We are applying the grounded theory approach here in the sense that we started from rather heuristic theoretical ideas on life-course, identity and education. According to these tentative ideas, individualization has become a major form of socialization in contemporary society and the life-course as a cultural product of the modern system has mainly tended to become institutionalized (Kohli, 1985; Meyer, 1986). The self and identity are essentially the outcomes of this kind of social reality production (Dannefer & Perlmutter, 1990). Educational institutions have had a central role both in the individualization of socialization, or enculturation, and in the institutionalization of life-course. In the context of social stratification, therefore, education is contributing to the production and reproduction of social and cultural inequality: as schools are places for making the core meaning of self and identity among young people, they are producing stratified or class identities (Wexler, 1992). In our study, we did not question the institutionalizing influence of education on life-course and inequality but we did make a hypothesis that the situation on the biographical level is more complex, and that education has several, also emancipatory, meanings. Revealing these meanings, we hope, will contribute to the realization of alternative futures and opportunities for change.

Finland as a Learning Society

In his Learning Society (1974) Torsten Husén gives a number of criteria for a learning society. In his view in a learning society:

- people have an opportunity for lifelong learning,

- formal education extends to the whole age group,

- informal education — such as adult studies — is in a central position and self-study is widely accepted,

- other institutions and organizations support education which in its turn depends on them.3

In the last chapter of this book two more recent projects of learning society presented in an Anglo-American context are investigated. There is not, however, any essential contradiction between Husén’s learning society and these two more recent cases.

Can Finland be characterized as a learning society? This question is central for this study. In order to consider it in context it might be best to start with an overview of the development of the Finnish society and the educational system of our country. The expansion of the education system has mainly followed the pattern established in other industrial societies, although with a certain time-lag. This lag is a result of our peripheral location in relation to the industrialized centres of Europe, even though Finland was an interface periphery between the nations of east and west. Finland remained more agrarian and less industrialized than other western European countries even as late as the 1960s.

Liter...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- 1. How to Study Peoples’ Lives?

- 2. The Meaning of Education

- 3. Biographical Method

- 4. Education in the Life-course of Three Generations

- 5. Cultural Construction of Educational Identity

- 6. Significant Experiences and Empowerment

- 7. Conclusion: Modernization and Education

- 8. Future Prospects: Towards the Global Learning Society?

- 9. Summary

- Notes

- Appendix 1: The Interviews

- References

- Index