- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Instruction Design for Microcomputing Software

About this book

Selected as one of the outstanding instructional development books in 1989 by the Association for Educational Communications and Technology, this volume presents research in instructional design theory as it applies to microcomputer courseware. It includes recommendations -- made by a distinguished group of instructional designers -- for creating courseware to suit the interactive nature of today's technology. Principles of instructional design are offered as a solid base from which to develop more effective programs for this new method of teaching -- and learning.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralI Instructional Design and Courseware Design

While the future viability and form of instructional courseware remains an unresolved issue, virtually every discussion on courseware contains some obligatory lamentations on the quality of existing courseware. If you peruse a broad range of existing courseware, those complaints are often justified.

What is the reason for this overall lack of quality? The authors in this book would provide unanimous support for Roblyer's (1981) claim that the poor quality results from the development methods, or lack thereof, used to produce the courseware. Their recommendation is that courseware designers employ a systematic method of instructional design to develop the courseware before the courseware is ever produced, marketed, or used. Systematic design procedures provide a useful methodology for producing any instructional materials, including microcomputer courseware. They would claim that courseware produced without using instructional design procedures based on instructional design theories and models is probably not instructional. Its intention may be instructional, but the result, as evidenced by the universal complaints about courseware, may not be truly instructional.

Instructional Design Theories into Models

Instructional design is a process and a discipline that derives from instructional theory. Reigeluth and Merrill (1979) have proposed that a theory of instruction must consist of methods, conditions, and outcomes. Instructional conditions describe the existing, situational factors (e.g., learner characteristics) which impact on learning. Instructional outcomes are the predetermined effects produced by instruction, that is, the learning effects which are to be produced by the instruction. Instructional methods are the means used to achieve the outcomes. These components are consistent with general systems theories which state that systems are goal-oriented, interactive, interdependent components, which adapt to maximize their output. Any theory of instruction, according to instructional design principles, needs to reflect those beliefs. An instructional design theory must therefore consist of "a set of principles that are systematically integrated and are a means to explain and predict instructional phenomena" (Reigeluth, 1983, p. 21). The instructional methods that derive from those principles comprise instructional design models. Instructional design models are manifestations of instructional design theories and are the means by which the theories are implemented. The models are important to designers who make decisions about the methods which should be used to produce instructional outcomes in given situations. However, the instructional theories on which the models are based are also important, because fallacious theories result in fallacious models which in turn result in ineffective instruction.

Instructional Design Models

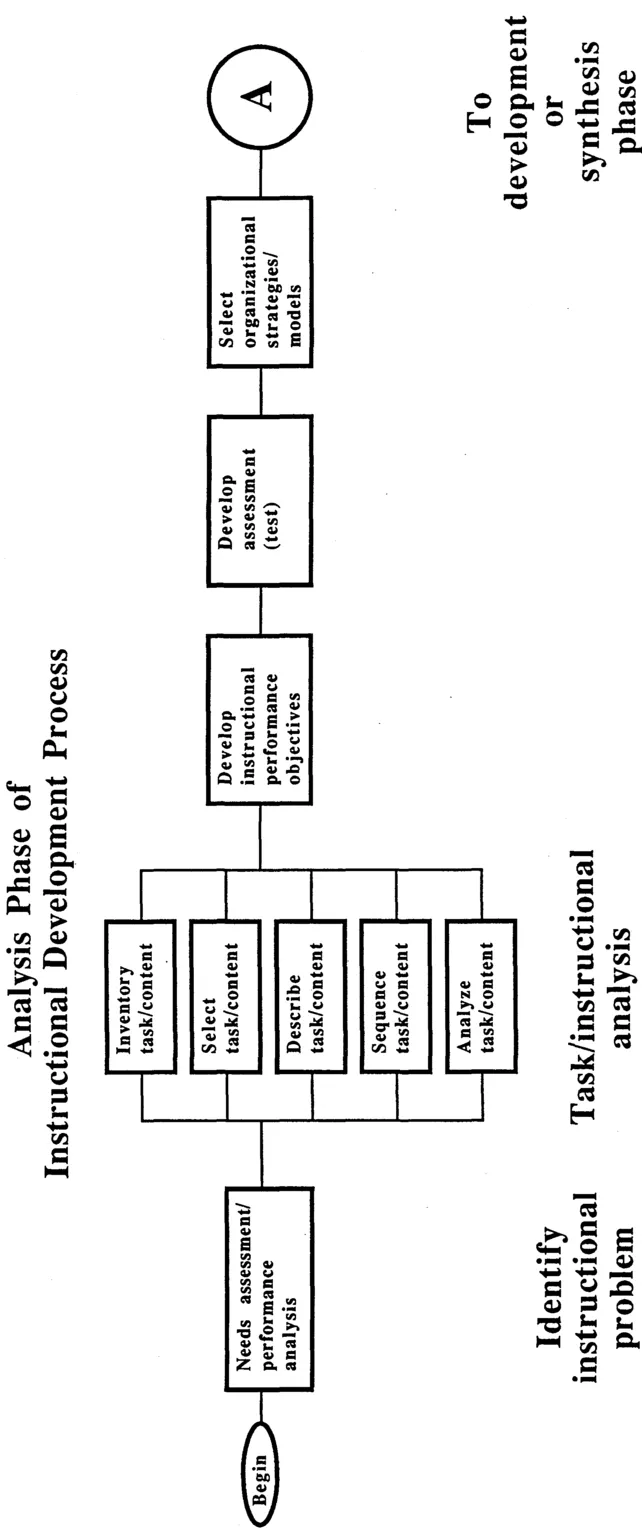

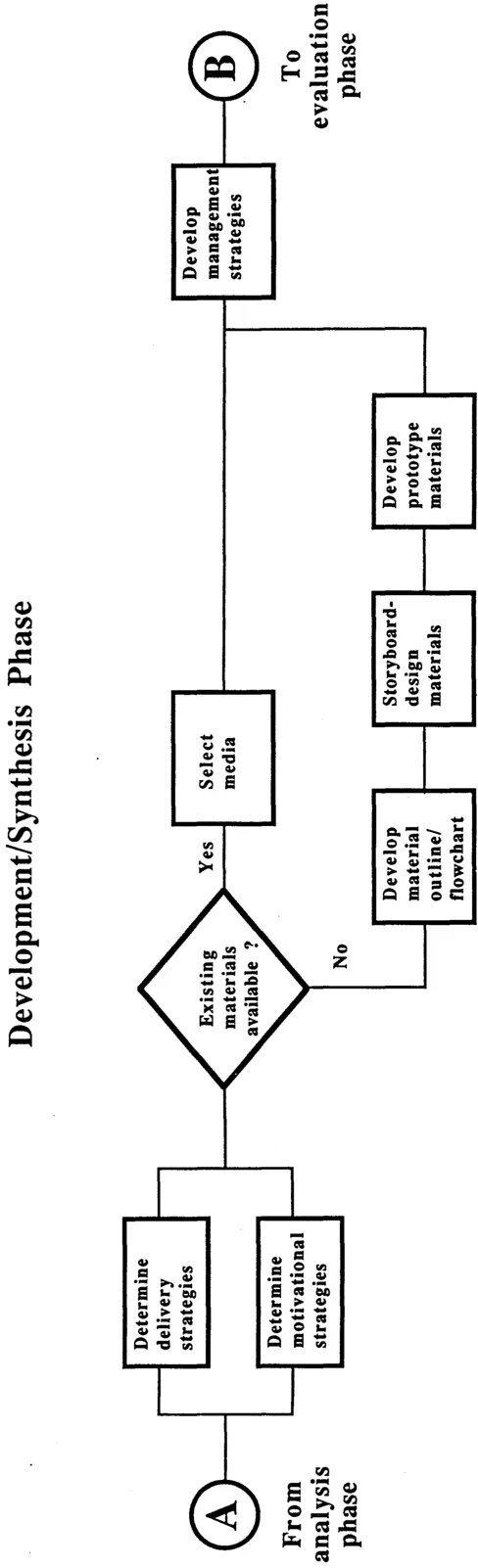

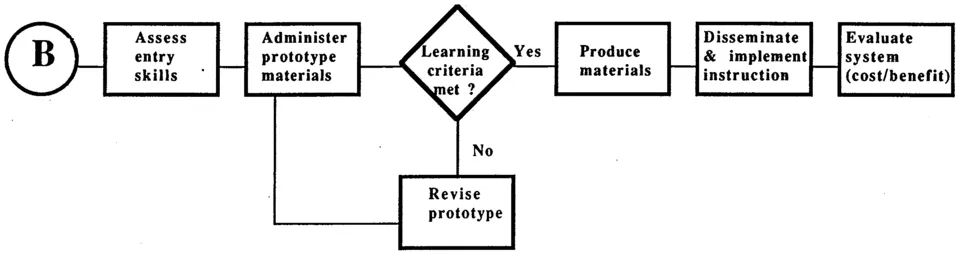

Andrews and Goodson (1980) compared forty instructional design models. While they found a good deal of disparity between the models (some of which are not really models), there is general agreement on the major components of the instructional development process. Figure I.1 illustrates the organization and arrangement of those components in a generic instructional design model. The instructional design process consists of three separate stages or phases. The first (Fig. I. 1a) is the analysis phase, in which the instructional conditions and outcomes are identified and preliminary decisions about instructional methods are made. In the second, development or synthesis phase (Fig. I.1b), methods decisions are completed and enacted, through either the selection or production of instructional materials or sequences. In the final evaluation phase (Fig. I. 1c), the methods decisions are evaluated in light of the conditions and outcomes and may be ammended accordingly. While instructional design models vary, most engage the designer in these three phases. This first section of the book, in fact, provides an interesting contrast between the two most prominent instructional design models in use today.

Introduction to Part I

Peggy Roblyer sets the tone for this first overview chapter with some well-documented lamentations, asserting that if CAI is to have a significant impact on education, more systematic design and development methods are essential. She

FIG. I.1a. Analysis phase of instructional development process.

FIG. I.1b. Development/synthesis phase.

FIG. I.1c. Evaluation phase.

education, more systematic design and development methods are essential. She identifies the specific problems in poor quality courseware (e.g., no objectives, lack of field testing), and the reasons for their occurence, which are, of course, a result of a lack of systematic design effort. She concludes by presenting and illustrating a process model for designing and developing courseware.

The next two chapters provide a useful comparison of the application of the two most prominent instructional design models in use—the events of instruction and component display theory. Walter Wager and Robert Gagné present the Gagné/Briggs model. They establish the context for the model by reviewing and exemplifying Gagné's taxonomy of learning outcomes and next relating instructional events to internal learning processes. After a brief review of courseware authoring, they illustrate the courseware development process by identifying the instructional components required for different learning outcomes. Although this design model is probably the best known, the fresh examples and courseware orientation make this a most useful contribution.

Finally, David Merrill presents the implications of component display theory (CDT) for courseware design. CDT is certainly one of the most coherent and cohesive micro-instructional design models available. As Merrill points out, when combined with elaboration theory or learner control, it provides one of the most comprehensive design systems available. After describing component display theory, Merrill provides a variety of excellent examples of how it can be applied directly to the courseware design process. These first three chapters function as an organizer, setting the stage for the remainder of the book. Instructional design is the context for considering the components of the courseware design process presented in the succeeding chapters.

Limitations of Instructional Design Models

Although it is the contention of the authors in this first section that instructional design models are useful in designing and producing microcomputer courseware, these models are not foolproof (nor would the authors suggest that they were). The quality of microcomputer-based instruction depends on careful design, we all agree. In addition to the variability in systematic design procedures, the best designs don't compensate for the lack of skills needed to develop quality instruction (Montague, Wulfeck, & Ellis, 1983). Inadequate designers, despite the quality of the design models, will produce inferior quality instruction. Instructional design models function best as heuristics for designing courseware or any other form of instruction.

References

Andrews, D. H., & Goodson, L. A. (1980). A comprartive analysis of models of instructional design. Journal of Instructional Development, 3(4), 2-16.

Montague, W. E., Wulfeck, W. H., & Ellis, J. A. (1983). Quality CBI depends on quality instructional design and quality implemnetation. Journal of Computer-Based Instruction, 10(2), 90-93.

Reigeluth, C. M. (1983). Instructional design: What is it and why is it? In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models: An overview of their current status. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Reigeluth, C. M., & Merrill, M. D. (1979). Classes of instructional variables. Educational Technology, 18(3), 5-24.

Roblyer, M. D. (1981). Instructional design versus authoring courseware: Some crucial differences. AEDS Journal 14(4), 173-181.

1 Fundamental Problems and Principles of Designing Effective Courseware

M. D. Roblyer

Florida A & M University

Florida A & M University

Introduction

The first wave of the so-called microcomputer revolution in education, a period of unchecked enthusiam for computers in the classroom, appears to be at an end. Although school microcomputer purchases continue unabated, there are signs that educators are beginning to question the usefulness of computer-assisted instruction as the primary activity for this technology. Recent microcomputer usage surveys indicate that, while CAI still constitutes about half of all computer-related activity, there has been a substantial decrease in the number of teachers who perceive that this should be the primary role for computers (Becker, 1986). In secondary schools, from 10-30% more teachers than in the last survey see the computer's most important role as that of tools for applications such as word processing, data analysis, and problem solving.

Dissatisfaction with the quality of most available instructional software may be a catalyst responsible for these changing perceptions of CAI. Although Becker's study found that "poor quality of software" ranked below other problems such as money for computer resources and teacher training, it may be that courseware quality has ceased to be the most critical issue in light of decreasing dependency on CAI. It may also be that poor quality software has been instrumental in bringing about other frequently cited problems such as "teachers lacking interest in learning about computers." Observers and practitioners alike (Bell, 1985; Bialo & Erickson, 1985; Futrell & Geisert, 1985) confirm that poor courseware quality continues to be a critical concern.

Certainly, it is becoming more difficult to make a case for increased across-the-board implementation of CAI on the basis of research results. A review of past CAI uses from 1965-85 (Roblyer, 1985) indicates that effects on learning vary widely depending on product design and implementation, and that CAI may often not be as effective in raising student performance as other, less expensive nontraditional methods. The impact of computer courseware on education is especially disappointing in light of the tremendous expectations voiced for it when microcomputers first began to appear in schools. This disenchantment has brought about a second wave of the microcomputer revolution in education, one which stresses analysis and accountability. As Beck...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- PART I: INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN AND COURSEWARE DESIGN

- PART II: INTERACTIVE DESIGNS FOR COURSEWARE

- PART III: ADAPTIVE DESIGNS FOR COURSEWARE

- PART IV: TOWARD INTELLIGENT CAI ON MICROCOMPUTERS

- PART V: DESIGNING MOTIVATING COURSEWARE

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Instruction Design for Microcomputing Software by David Jonassen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.