- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Residential Layout

About this book

Introduction to Residential Layout is ideal for students and practitioners of urban design, planning, engineering, architecture and landscape seeking a comprehensive guide to the theory and practice of designing and laying out residential areas.

Mike Biddulph provides a clear and coherent framework from which he offers comprehensive practical advice for designers of housing developments. Referring to a wealth of international examples, this is a richly illustrated, accessible resource covering the whole range of issues that should be considered by

anyone engaging in the planning and design of a new residential scheme.

A successful residential development must work on many levels – financial, social and environmental. This book includes analysis of commercial viability, the importance of place making, environmental sustainability and designing accessibility. Mike Biddulph details successful approaches to designing out crime and maximising permeability as part of an integrated approach to urban design.

Highly illustrated throughout, this work will show you how to turn design aspirations and principles into practical design solutions. Written without preconceptions, Introduction to Residential Design

highlights the strengths and weaknesses of particular design solutions to encourage both depth of thought and creativity.

Mike Biddulph is Senior Lecturer in Urban Design at Cardiff University

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | Introduction |

THE DESIGN OF RESIDENTIAL AREAS

This book aims to bring together current thinking on the design of residential areas to provide a comprehensive source of practical advice for anyone responsible for the layout of a residential scheme. It tries, in particular, to combine current thinking about residential layout with reference to a wide range of examples of good practice from actual schemes. This is done so that the practical value of the ideas presented in this book is always apparent.

Housing environments take up the majority of developed land and we spend long periods of our life within them. As such the way that they are designed can simply make our lives a pleasure, or they can make it hard for us to live our lives the way that we would like. How they are designed can, in particular, open up or reduce opportunities for us. It is important that in planning any residential scheme, designers are conscious of the design choices that are available to them so that these can be either encouraged or rejected through the design process. This book aims, therefore, to suggest that there is a whole range of design options available to us in the design of residential schemes. It also tries to show us what the consequences of the design choices that we might make are, so that, as designers, we are informed in our decision-making.

This book is not about residential architecture, and it won't tell you how to design and construct a house. Instead, it is a book about residential urban design. In this respect the use of the term ‘urban’ is loose, and merely refers to situations in which a group of buildings come together to form villages, towns or cities. The focus is more specifically on the places that are created as a result of the planning and layout of individual homes–more explicitly the gardens, streets, yards, parks and other attributes that characterise the spaces between our homes. This book points out the problems associated with particular approaches to laying out houses. In particular, it aims to be optimistic and encourage an understanding of the possibilities that are realised when the planning of a housing scheme is undertaken.

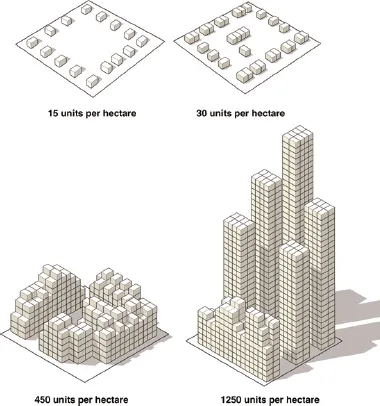

In order to do this, however, it has been necessary to focus on a type of residential development. When you think about it, there is a whole range of environments which have been designed for human habitation, and it wouldn't be sensible to try and write a book that would be relevant to all these forms. This book therefore focuses on the types of environment that result from certain densities of development. Rudlin and Falk (1999) illustrate how Kowloon, north of the Hong Kong island, has a density of 1,250 units per hectare, whilst the average net density of Los Angeles is 15 units per hectare (Figure 1.1). This book will be of little interest to you if you are planning schemes at either of these extremes. Instead the book is concerned with the design of residential environments at a medium density of between about 30 and 450 units per hectare. This itself is a wide range, but for anything above 30 units per hectare many of the layout issues in this book become more pertinent, whilst densities of 450 units per hectare, despite being high, reflect common densities achieved, for example, in the centre of London (see Llewelyn Davies, 2000). High quality residential environments are still commonplace at such densities, even if they really do start to restrict the types of layout qualities that you might aspire to achieve.

Figure 1.1 Visualising units per hectare

SUSTAINABLE SCHEMES

This book considers a range of issues associated with residential layout from a variety of perspectives, but all of the content is organised around the principle that the planning and design of new residential areas should create physical conditions where economically, socially and environmentally sustainable lifestyles become possible. Economically, this means that housing should form part of a wider environment that remains popular with not only the initial residents but also subsequent residents, while commercial and community uses should be designed and integrated into any plans so that they remain viable. Socially, this means that the designs should allow residents to have equity of access to housing, the wider environment or facilities and that all residents (whatever their relative affluence) should be able to enjoy a good quality of life. Environmentally, this means that the designs should create conditions where resource consumption can be minimised and biodiversity within or around the residential schemes are sustained or enhanced.

It is possible to design residential areas which favour economic, social or environmental concerns; for example, an exclusive residential area which is economically very successful and socially unmixed and which offers a wide range of facilities, but only for immediate residents. Such schemes would, however, exclude other people who may not have access to similar opportunities elsewhere. Equally, it is also possible to design commercial uses into a scheme that will be extremely viable but dependent exclusively on people who are auto-dependent. Such a plan would exclude residents without access to a car, and the scheme would also have poor environmental credentials. Ultimately it will be your, or your client's, choice as to how you respond to the challenge of creating sustainability, but the objective of this book has been to present an approach in which a whole range of issues are considered in a balanced way. At least then it will be possible to critically appreciate the nature of the choices being made and the range of options available.

Figure 1.2 It is possible to design a residential environment in which people might not feel too comfortable about walking

DESIGN CHOICES AND LIFESTYLE OPPORTUNITIES

The design of urban spaces won't determine how people will live within the residential area. However, as already suggested, it will create or limit opportunities for people. For example, it is possible to design a residential environment in which it would be difficult or unpleasant to walk (Figure 1.2). Even in situations like these, people may still choose to walk as they adapt quite successfully to their environment, and walking may be the only way they can get around. A better design, however, would have acknowledged the needs of the pedestrian and involved a design that would support that need.

However, maintaining these options involves difficult decisions, and to a certain extent the designers of residential areas must exercise value judgements in deciding which choices should be available to residents. Some choices might be obvious; for example, providing people with the opportunity to walk to local facilities would appear to be an obvious choice. Other choices, in contrast, might have an economic, social or environmental cost attached to them. Making it possible for residents to drive quickly through a residential area may be good for people who choose to drive, but it will encourage car use and probably make the residential area more dangerous. This in turn would limit the extent to which children would be allowed to play in the street, whilst elderly people might feel more insecure outside their home (Figure 1.3). Designers, therefore, must be conscious of the consequences of their design decisions and the fact that creating opportunities for certain types of activity might directly limit the choices of some individuals. Again, this book tries to highlight in what ways design decisions might create or limit choices in how people might choose to live within an area, whilst it also considers the positive and negative consequences of the range of design solutions that are available.

Figure 1.3 Designers need to understand the implications of their design choices

BLAND HOUSING

A common criticism of many residential areas is that they are all fundamentally the same. This is far from the case, but there certainly is a tendency towards a standard form of suburban development in, say the USA and UK, for example.

In the USA and UK, residential development is often dominated, in particular, by detached houses ‘strung out’ along very standardised roads, and the miles and miles of these roads come to define what we collectively, and sometimes a little dismissively, call ‘suburbia’ (Figure 1.4).

There is actually a lot of variation within suburbia, and this form of housing remains very popular. It is not therefore, the purpose of this book to be ‘anti-suburban’. Its purpose is, however, to explore the variety that does exist in the form of both urban and suburban housing to illustrate what is actually possible for the forces of standardisation to be overcome. There are three main forces of standardisation.

Figure 1.4 American suburbia

Standard house types

Developers design and want to build standard, tried and tested, houses. This is actually quite a good idea. It keeps costs down, and the developers can guarantee the quality of the home to a greater extent. String the same houses unimaginatively out along a road, however, and soon everywhere starts to look and feel the same. It is possible to use either individually designed or standard house types, but to use them in such a way that greater variety in a residential area is achieved (Figure 1.5).

Standard roads

Engineers want to build and maintain a limited number of standard, tried and tested, roads. This is also a good idea. When roads are tried and tested their performance is more predictable. It is necessary to suggest, however, that some engineers may not be aware of the whole...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Photographic sources

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Ensuring commercial viability

- 3 Building place and defining space

- 4 Environmentally benign development and design

- 5 Access and movement

- 6 Integrating other uses

- 7 Safe and easy to find your way around

- 8 Contemporary residential townscape

- 9 Social life in outdoor residential spaces

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Introduction to Residential Layout by Mike Biddulph in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.