- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This important new book bridges the gap between works on classical control and process control, and those dealing with HVAC control at a more elementary level, which generally adopt a qualitative and descriptive control. Both advanced level students and specialist practitioners will welcome the in-depth analytical treatment of the subject presented in this volume. Of particular significance are the current developments in adaptive control, robust control, artificial neural networks and fuzzy logic systems, all of which are given a thorough analytical treatment in the book.

- First book to provide an analytical treatment of subject

- Covers all new developments in HVAC control systems

- Looks at systems both in the UK and abroad

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I HVAC control systems

I. I Basic concepts

It is not frequently acknowledged that heating, ventilating and air conditioning (HVAC) systems present one of the most challenging situations to deal with from the point of view of control. Swings in day-to-day, week-to-week and season-to-season energy demand together with the infinitely complex combination of user needs at the human interface contribute to a highly non-stationary ‘environment’ within which control takes place. It is little wonder then that much of HVAC control is about compromise; a compromise that usually amounts to reasonable comfort at minimum energy use and cost.

HVAC control in common with all process system control requires the governance of two distinct actions; those of switching or ‘enabling’ and regulating or ‘adjustment’. Switching in the majority of applications amounts to ensuring that the plant is available at certain times of the day (generally, those times of the day in which a building is in use). This will be essentially clock-based, occupancy-sensor-based or indeed based on some other logical two-state condition such as an alarm state. Regulation, which is what this book in essence is about, amounts to ensuring that the plant capacity is matched to the demands placed upon the system.

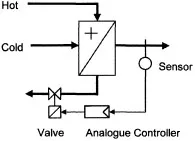

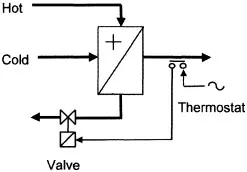

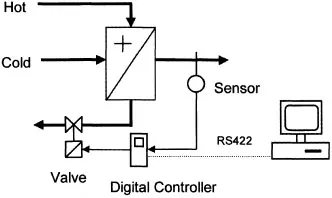

Let us consider some basic concepts of HVAC control. Figures 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 show three quite contrasting ways of controlling the output of a simple heat exchanger. The actions of these three systems are quite different.

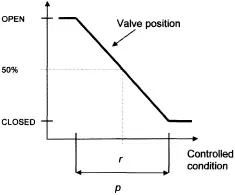

Under analogue control, the controller positions the valve anywhere between fully open and fully closed (Figure 1.4) using a smooth continuous signal from the controller. Control is defined in terms of a reference condition or set point (r) and a proportional band (p) which represents the range of the controlled condition for which the output of the controller is proportional. Figure 1.4 for instance shows that the valve will settle at the set point at 50% of its range and, during fluctuating conditions, the temperature will drift either side of the set point until control action restores its value at the latter. This was the predominant method of HVAC system control until the early 1980s and still exists today in the form of mechanical direct-acting control devices. For example, the ‘thermostatic’ radiator valve (TRV) is one case of this type of control.

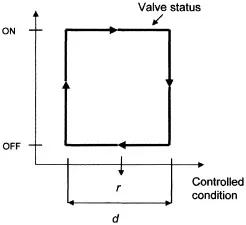

Under thermostatic control, control is a two-state process. The thermostat is a switching device and positions the valve periodically in either a fully closed position or a fully open position; there are no in-betweens. Control action is defined in terms of a set point and dead band (d) which represents a band of inactivity the limits of which form switching events (Figure 1.5). This method of control is widespread; there are numerous examples in the home such as the domestic iron and the portable electric fan heater. It has the advantage of achieving reasonably effective control with great simplicity but the disadvantages of a fluctuating controlled condition (within the limits of the dead band) and the frequent switching of equipment which in some cases can cause excessive wear on components. For these reasons it is not used commonly in the UK for conventional HVAC control but is used widely for domestic heating, unitary air conditioners and small-scale atmospheric boilers.

Figure 1.1 Analogue control.

Figure 1.2 Thermostatic control.

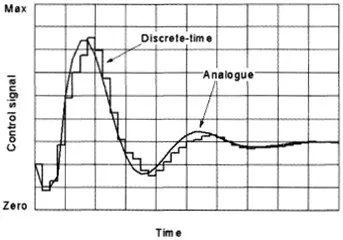

Figure 1.3 Digital control.

Figure 1.4 Proportional control action.

Figure 1.5 Thermostatic control action.

Figure 1.6 Typical analogue and digital control signals.

Under digital control, control action takes place at discrete points in time, each point separated by a time interval, T. The valve position will assume a position anywhere between fully open and fully closed according to a calculation carried out by the controller at each discrete point in time (Figure 1.6). In between these times, control action freezes. Digital control offers enormous flexibility particularly when the controller forms part of a network linked to a supervisory computer. The controller can be designed as a ‘stand-alone’ for the specific task, merely requiring setting up and adjustment for precise plant conditions – application-specific controller (ASC) – or freely programmable for whatever task is intended – universal controller (UC). Alternatively, parametric control decisions and actions can be performed by the central supervising computer with local control decision-making and signal management carried out at the plant ‘level’ by programmable intelligent outstations.

Whether networked or stand-alone application-specific, this type of control is now the predominant method for conventional non-domestic HVAC systems and plant.

We will now move on to take a look at some of the established applications of HVAC control.

1.2 HVAC control strategies

Constant-volume air handling

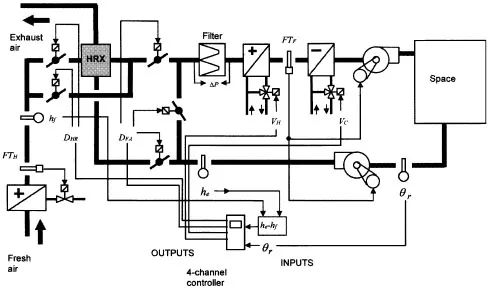

Figure 1.7 shows the general arrangement for the four-channel control of an air handling system serving one zone in which the four channels control, in sequence, heating → heat recovery → fresh air (‘free’ cooling) → chilled water-based cooling.

Note that the heat recovery is optional and would only tend to be used in this application when the minimum fresh air in total air handled is high due, for instance, to high occupancy density in the zones served by the air handling system. Note also that the controlled condition becomes supply air temperature in situations where the air handling system’s function is to provide pre-conditioned air to rooms or zones which themselves have local sequenced heating and cooling control.

Operation The controlled condition is the space temperature, θr. It is usual to measure this in the return air duct, provided that there are no intervening heat gains, such as light fittings, in the return air path. The return air will be well-mixed and the temperature sensor at the higher in-duct air velocities will tend to be more responsive than in the comparatively still air conditions of the space. For space or room temperature control, the manipulated variables will be:

• the flow rate of heating water by means of diverting control valve, VH;

• the proportion of direct and bypass air at the heat recovery heat exchanger, HRX, by means of face and bypass dampers, DHR;

Figure 1.7 Control for constant-volume air handling.

• the proportion of fresh and recirculating air at the mixing dampers, DFA; and

• the flow rate of chilled water by means of diverting control valve, VC.

During very warm summer weather, the fresh air damper will be fully open and the heat recovery face and bypass dampers positioned for full bypass in order to achieve ‘free cooling’. The limit to free cooling is reached when the fresh air intake enthalpy exceeds the enthalpy of the return air at a point downstream of the return air fan, a condition that takes place during the peak summer season in the UK though will often be short-lived. At this condition, it is necessary to signal to the fresh air damper a return to its minimum position and for the heat recovery face and bypass dampers to reposition so as to allow full heat recovery (which will now, in effect, provide pre-cooling of the fresh air from the cool building exhaust air). Enthalpy sensors he and hf provide this and most control system manufacturers will permit additional plug-in modules for their multi-channel controllers to achieve these summer reset conditions. In the arrangement shown, when he – hf produces a negative signal, the reset conditions described are enacted.

To provide frost protection, there are two features. Firstly, the heat recovery heat exchanger (if present) is protected from icing during very cold weather by an upstream frost coil on the fresh air side. Because of the highly temporal nature of calls on the frost coil, a simple thermostatic control through a two-position two-port control valve is usually sufficient. Frost thermostat FTH provides for this. Secondly, should any primary heating plant such as central boilers or pumps fail, all coils in the arrangement are vulnerable to freezing of their respective water contents during very cold weather, especially the frost coil itself. To provide last-line protection against this, frost thermostat FTF acts to trip both fans (a further precaution might be to provide a two-position isolating damper at the fresh air intake which coincidentally closes in these conditions thereby eliminating any natural draught through the plant when idle). Typically, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 HVAC control systems

- 2 Device technology

- 3 System modelling

- 4 System stability

- 5 Discrete-time systems

- 6 Multivariable control

- 7 System identification and controller tuning

- 8 Adaptive control

- 9 Advanced methods

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access HVAC Control Systems by Chris P. Underwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Methods & Materials. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.