![]()

Part I

Individual Differences in Learning and Instruction

![]()

1

Individuals, Differences, and Learning

Introduction

As educators, we often wonder why some students find it difficult to learn whereas others find it easy. Why are students better equipped to learn some skills but not others? Why can’t all students learn all skills equally well? Student learning differs because student learning traits differ, and because the thinking process differs depending on what the student is trying to learn. First, student learning traits differ. Individuals vary in their aptitudes for learning, their willingness to learn, and the styles or preferences for how they learn if they choose to. These differences impact the learning process for each student. That is, these learner traits determine to some degree if and how well any individual is able to learn. Second, the nature of the thinking and learning processes varies with the task. The outcomes of learning require that students think in different ways. Third, learner traits interact with learning outcomes and the thinking requirements entailed by them. Different learners will have varying aptitudes for different learning outcomes. This first chapter briefly describes these differences in traits and learning outcomes:

We begin by defining some assumptions about individuals and how they learn. The following assumptions form the structure of this chapter and the foundation for the arguments presented in subsequent chapters.

- Individuals differ in their general skills, aptitudes, and preferences for processing information, constructing meaning from it, and applying it to new situations.

- Individuals also differ in their abilities to perform different school-based or real-world learning tasks and outcomes.

- Different school-based or real-world learning tasks and outcomes require the use of different skills, aptitudes, and preferences.

- These general abilities or preferences affect the student’s ability to accomplish different learning outcomes; that is, one’s learning aptitude interacts with the accomplishment of learning tasks and outcomes.

Individual Differences in Learning Traits (Aptitudes, Skills, and Preferences)

Learning is a complex process. It requires that a student is willing or motivated to learn, that a student is able to learn, that a student is in a social and academic environment that fosters learning, and that the instruction that is available is comprehensible and effective for the learner. This chapter first focuses on the learner traits that motivate and enable a student to learn. The following list of learner traits (described in subsequent chapters) represents a broad range of differences that span from specific abilities to general styles:

General mental abilities (intelligence)

Hierarchical abilities (fluid, crystallized, and spatial)

Primary mental abilities

Products

Operations

Content

Cognitive Controls

Field dependence/independence (global vs. articulated style)

Field articulation (cognitive flexibility)

Cognitive tempo (reflectivity/impulsivity)

Focal attention (scanning/focusing)

Category width (breadth of categorizing)

Cognitive complexity/simplicity

Strong versus weak automatization

Cognitive styles: Information gathering

Visual/haptic

Visualizer/verbalizer

Leveling/sharpening

Cognitive styles: Information organizing

Serialist/holist

Conceptual style

Learning styles

Hill’s cognitive style mapping

Kolb’s learning styles

Dunn and Dunn learning styles

Grasha-Reichman learning styles

Gregorc learning styles

Personality: Attentional and engagement styles

Anxiety

Tolerance for unrealistic experiences

Ambiguity tolerance

Frustration tolerance

Personality: Expectancy and incentive styles

Locus of control

Introversion/extraversion

Achievement motivation

Risk taking vs. cautiousness

Prior knowledge

Prior knowledge and achievement

Structural knowledge

This list of individual differences describes the range of learner traits. These traits, described in subsequent chapters, are of several types that range from specific abilities to general styles. The first type describes intellectual aptitudes for learning. We eschew use of the term intelligence because it is too complex, yet too vague, and cannot be correlated with the specific learning requirements of instructional approaches. It is also inconsistent with the geographic metaphor that we use to describe individual differences. Although we all share some understanding about what it means to be intelligent, the term has different meanings for each of us. Also, the sources and causes of intelligence vary. Some people appear to be intelligent because they are experienced, others because they are fluent in language, others because they can comprehend and use abstract ideas. Because of these complexities of the concept of intelligence, we choose to describe it in terms of its constituent mental abilities, both primary and secondary.

The next types of traits are cognitive controls and cognitive styles. The particular combination of mental abilities possessed by an individual determines an individual’s cognitive controls and styles. These controls and styles describe how an individual interacts with his or her environment, extracts information from it, constructs and organizes personal knowledge, and then applies that knowledge. Cognitive controls are more closely related to mental abilities, whereas cognitive styles describe more general perceptual and processing characteristics, that is, more general tendencies.

The next type of traits, learning styles, describes learner preferences for different types of learning and instructional activities. These styles are generally measured by self-report techniques that ask individuals how they think that they prefer to learn. As such, they are not tied directly to mental abilities, but rather to more general learner perceptions of their own preferences. They are, however, related to mental abilities because most of us prefer to use the mental abilities and cognitive controls and styles with which we are more skilled and familiar.

Individuals also differ in their personalities, another type of learner traits. Personality describes how an individual interacts with his or her environment and especially with other people. Some see personality as the overarching theory that subsumes all individual differences (see Introduction to part 7). Personality is a complex of mental dispositions to behave in certain ways. In this book, we describe only those personality traits that more directly affect learning. We do not intend to review the entire field of personality.

Finally, individuals differ in their kinds and levels of prior knowledge, an important learner trait. Prior knowledge does not describe the ability to know or one’s preferred mode of coming to know--just what the individual already knows. Included in this term is prior structural knowledge (what people know and how it is organized) as well as prior achievement. Achievement describes the skills and learning abilities that individuals have previously acquired. Both types of prior knowledge are important predictors of how well an individual is able to learn new ideas and skills.

The large number of learner traits denotes the complexity of the individual learner and the learning process. It is important to note that these are traits, that is, general learner abilities and skills. Specific task-related skills call on combinations of these traits. Each of these traits is treated in greater depth later in the book.

Individual Differences in Learning Tasks and Outcomes

Individual learning varies also because of the mental processing required by the learning task. That is, learning and acquiring different skills and knowledge will demand the use of different sets of traits. A common criticism of schools is that they teach only the rote memorization of facts. In truth, students engage in many complex forms of learning. The types of learning that are required in schools and other educational settings are usually described in terms of taxonomies of learning.

A taxonomy is a classification scheme that orders objects or phenomena hierarchically. That is, terms at the top of the taxonomy are more general, inclusive, or complex, subsuming terms at a lower level. Taxonomies are used commonly in the natural sciences to classify animals, plants, elements, and so on. Teachers and instructional designers use taxonomies of learning outcomes to classify either the instructional objectives (or goals) to be accomplished or the test items used to evaluate these goals. Behaviors at the top levels of the taxonomy are more complex than lower level behaviors. Lower level behaviors are prerequisite to higher level behaviors. That is, any level of behavior is dependent on the capability of a learner to perform at the next lower level which is, in turn, dependent on the next lower level ability and so on.

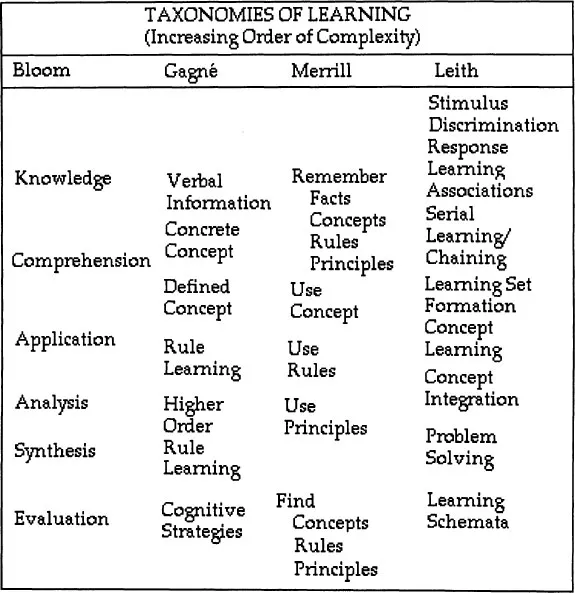

In this section, we briefly present four different learning taxonomies (see Fig. 1.1 for a comparison) that may be used to classify learning outcomes. As you read them, focus on the similarities and differences between these taxonomies. All are presented in a sequence that describes first the easier, lower level skills, and then moves on to the more difficult, higher level outcomes.

Fig. 1.1. Taxonomies of learning.

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Objectives

Bloom is best known for his Taxonomy of Cognitive Objectives (Bloom, Englehart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956; Furst, 1981) that described the range of cognitive behaviors--intellectual abilities or skills involving recall or use of knowledge--which are found in educational testing. Most stated educational outcomes are described by this domain. Bloom also helped to develop taxonomies of affective (interest, attitudes, and values) outcomes (Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia, 1964) and the psychomotor domain of behaviors including physical, manipulative capabilities involving the senses of touch (kinesthetic) and balance (proprioception) and including typing, sports, and mechanics. In this book, we consider only the cognitive outcomes of learning, which are described in the following hierarchy of learning types.

Knowledge Level. Learning at the knowledge level involves only the recall of facts, terminology, methodology without understanding. Sometimes, knowledge level behavior sounds complex, but no comprehension is expected. For example:

- What is the capital of Zaire?

- State the memory requirement for operating a specific software package.

- State the procedure for discarding Class 6 toxic chemicals.

Comprehension. Comprehension involves elementary understanding and use of knowledge, such as translation, and interpretation. For example:

- Identify examples of pragmatism from the front page of the newspaper.

- Translate the directions for assembling the machine into French.

- Determine preference rankings from bar and circle graphs.

Application. Application requires the abstraction of a rule or generalization from knowledge. The learner then applies it to solve a related problem. For example:

- Determine the hypotenuse of a right triangle.

- Select the appropriate nonparametric statistic to use in analyzing survey data.

- Decide which bedding plants to use in a garden at 7,500 feet above sea level.

Analysis. Analysis involves investigating a knowledge domain, breaking it down, and identifying its component elements and the relationships between those elements. Analysis requires determining the structure or organization of a set of ideas. For example:

- Determine the logical flaw in the traffic flow plan in the downtown area.

- Based on stylistic criteria, decide which 20th century novelist wrote this passage.

- Determine the causes of contaminated reactants in a process.

Synthesis. Knowledge that has been analyzed can be reassembled into a new form of communication. Deriving a new plan from the elements of the old is synthesis. For example:

- Develop an advertising campaign that conveys stability and reliability.

- Develop a legal defense for a client based on the recent Supreme Court ruling.

- Design a needs analysis that will identify the most significant problems of the organi...