1 Introduction

- Four discourses

- Plan of the book

- A note for readers

What should the unit of analysis of ‘agency’ be in organizational change theory? Is it possible to integrate competing concepts of agency into a coherent theory of organizational change? Can we have theories of organizational change without purposeful or intentional concepts of agency?

Fifty years ago these perplexing questions were often answered positively. Archetypes of agency were identified with models of rational actors and organizational change was conceived as a process that could be effectively planned and managed to achieve instrumental outcomes. A classic exemplification of this rationalist view is Lewin’s concept of the ‘change agent’ as an expert facilitator of group processes of planned change, although his original concept has gone through many reformulations within various traditions of organization development theory and consultancy practice (Schein 1988).

Outside the organizational development tradition, however, overrationalized models of agency and organizational analysis have been challenged from their very inception, both theoretically and practically. Simon’s (1947) persuasive critique of decision-making processes in complex organizations is still a classic starting point for ‘processual’ and ‘contextualist’ attacks on the rationalism propounded by corporate planners, functional specialists and other experts (Mintzberg 1994; Pettigrew 1997). His work also anticipated later ideas on ‘logical incrementalism’ and ‘emergent’ concepts of strategy and organizational change, although this has rarely been acknowledged (Quinn 1980).

Challenges to rationalism, planned organizational change and expertise have also emerged from far-reaching transformations of the workplace over the past two decades. During the 1980s post-Fordist models of organizational flexibility and new modes of information technology radically undermined the idea that organizational success depended on traditional bureaucratic modes of workplace authority, stability and control (Castells 2000). Managerial agency and leadership was no longer identified primarily with the traditional roles of instructing, directing and controlling work processes. Instead, managers and leaders were now expected to encourage ‘commitment’ and ‘empower’ employees to be receptive to culture change, technological innovation and enterprise. The new vehicles for this ‘dispersal’ or distribution of change agency were new self-managed teams, quality circles and task groups, which acted as internal agents of transformation and change, as well as sources of distributive knowledge and expertise (Nonaka 1994; Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995).

This overall picture of a gradual shift or dispersal of change agency in organizations towards decentred groups or teams has been popularized in concepts of the ‘learning organization’ and more recently in the idea of ‘communities of practice’ (Senge 1990, 2003; Wenger 1998). Although the genealogy of these concepts is complex, they broadly conceive of organizations not as top-down structures of rational control, but as loosely coupled systems, networks or processes of learning and collective knowledge creation that devolve autonomy to agency at all levels (Dierkes et al. 2001). These ideas are, of course, partly a recognition of the fact that central hierarchical control has declined in many organizations and that large-scale organizational change is simply too complex and high-risk for any one group or individual to lead. It is in these terms that proponents of the learning organization have rejected the bureaucratic and mechanistic idea that organizations ‘need change agents’ and leaders who can ‘drive change’ (Senge 1999). Instead, leadership and change agency become identified with the systemic selforganization of learning by broadening leadership theory to encompass participative models of learning across the whole organization.

One finds similar ideas of the dispersal and decentring of agency within complexity theories of organizations. These theories have become increasingly influential over the past decade, as managing change has become synonymous with coping with the challenges of chaos (Anderson 1999; Fitzgerald and Van Eijnatten 2002). Although complexity and chaos theories have their origins in physics, computer science and mathematical biology, they have often been transposed into discussions of organizational change as well as broader ideas of the ‘hypercomplexity’ of network organizations and societies, and concepts of ‘disorganised capitalism’ (Brown and Eisenhardt 1997; Anderson 1999; Urry 2003). In all these theories the central idea is that dynamic systems are in a constant state of self-organizing stability–instability, which allows them to adapt and change. This occurs through ‘dissipative structures’ or devolved networks of information interchange that allow order and chaos, continuity and transformation to occur simultaneously, and without the hidden hand of purposiveness or central control. Effectively, ‘order is free’ since it appears to emerge from simple bottomup processes or rules that create non-linear dynamics of bounded instability (Kauffman 1993). Applied to organizational change theory these ideas have encouraged a rejection of conventional rationalist subject–object dichotomies of knowledge creation, concepts of ‘centred agency’ and a reinterpretation of organizational change and change agency as an emergent, self-organizing and temporal process of communication and learning (Stacey 2001; 2003).

While this brief history of the growing diversity and plurality of forms of agency in organizations can be plotted in relation to transformations of the workplace, it can also be delineated in terms of an overall transition from rationalist epistemologies of agency to the increasingly fragmented discourses of ‘social constructionism’ and ‘organizational discourse’ analysis (Gergen 2001a; Grant et al. 2004). Rationalist epistemologies of agency have, of course, a long and complex intellectual genealogy in philosophy, but broadly they are characterized by a belief in human beings as rational subjects or autonomous actors who can act in an intentional, predictable and responsible manner toward predetermined goals or planned outcomes (Davidson 2001; Giddens 1984). These assumptions are essential in creating ‘objective’ ideals of rational scientific knowledge and its application to human action and practice, including universal ideals of ethical behaviour. Rationalist epistemologies are therefore scientific, prescriptive and interventionist. In contrast, the multi-various forms of social constructionism invariably undermine science and rationalism and with it ideals of agency and organizational change centred on rationality (Foucault 1994). Not only does knowledge of the natural world not have a predetermined structure or laws discoverable by rational investigation, but also ideas of ‘human action’, ‘personality’, ‘intentionality’ and ‘agency’ are equally problematic. For social constructionists and organizational discourse theorists, all forms of knowledge, understanding and action are culturally and historically relative and must therefore be situated within competing discourses (Hardy 2004).

This brief historical and epistemological overview of the nature of agency and change in organizations charts a profound and increasingly disconcerting transformation. From a position of great optimism regarding the practical efficacy and potential emancipatory role of rational action, expert knowledge and ‘change agency’, we now confront a plurality of conflicting ideals, paradigms and disciplinary self-images that are increasingly difficult to meld together in any coherent manner. We must ask how this fragmentation occurred, and what epistemological implications it has for understanding the future prospects for modes of agency and change in organizations, as well as concepts of practice. Should we give up the search for an ‘integrated paradigm’ or interdisciplinary ideal of change agency that goes beyond the Babel of increasingly competing discourses and the disparate contingencies of practice? Or, should we accept the plurality of discourses and the eclecticism of practice as itself a positive affirmation of new and more positive ideals of decentred agency?

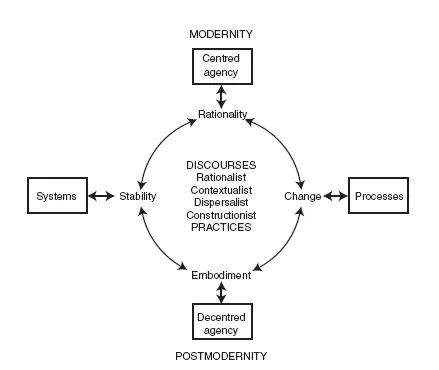

This book presents a selective, synthetic and critical historical review of some of the literature and empirical research on agency and change in organizations. The review, however, is not strictly chronological and takes the form of a heuristic classification of change agency and organizational change theories using two conceptual continua: centred agency–decentred agency and systems–processes (see Figure 1, p. 5). Centred agency refers to intentional forms of rational and autonomous action, while decentred agency refers to emergent and ‘embodied’ forms of action that are enacted through practice. Systems define the relatively ordered and stable properties of organizations conceived as ‘structures’, while processes encompass emergent aspects of organizational change and instability. The poles of each continuum are conceived generically as analytically useful contrast concepts that reconfigure the familiar, if increasingly problematic, dichotomy between agency and structure (Giddens 1984).

The agency–structure dichotomy invariably reproduces varieties of ontological or epistemological polarity: agency without structure (i.e. voluntarism) or structure without agency (i.e. determinism), as well as many intermediate theoretical variants. The two continua are designed to avoid this polarity, while shifting the analytical focus from agency and structure to agency and change. The theoretical rationale for this shift is briefly outlined in Chapter 2, which begins by examining Giddens’ (1984) classic reformulation of agency and structure as the ‘duality of structure’. While a case is made for a move away from the agency–structure dichotomy, it is argued that we must retain multifaceted conceptions of agency related to change (Caldwell 2005b).

Figure 1 Discourses on agency and change in organizations

Four discourses

The four discourses can be broadly defined as follows.

Rationalist discourses identify intentional action and agency with rationality, expertise, autonomy and reflexivity, and this is amplified in the corresponding idea that human behaviour and organizations are ordered or ‘functional’ systems that can be subject to planned change or expert redesign, even in the face of resistance.

There is a vast range of rationalist discourses of intentional and teleological agency in the social sciences, from rational choice models of economic action to cognitive theories of instrumental behaviour. In the field of organization change theory, however, the most influential rationalist discourses on change agency have their origins in the influential work of Kurt Lewin (1947, 1999), although his ideas have gone through many reformulations within the various traditions of organizational development (OD) research and practice. Broadly, the four key attributes of an intentional or centred concept of change agency are invariably synonymous with the Lewinian legacy and the OD tradition: rationality and expertise, and to a lesser extent, autonomy and reflexivity.

Contextualist discourses conceive human agency as embedded in emergent processes of organizational change that are not predetermined by internal structural contingencies or external environmental factors, but are rather the outcomes of non-linear, multi-level and incremental transition processes open to choice by human agents who operate within contexts of ‘bounded choice’ defined by competing group interests, organizational politics and power.

Broadly conceived contextualist discourses have a long and distinguished academic lineage, crossing a range of disciplinary fields and assuming many sub-varieties. One can find genealogical links between Simon’s (1947) critique of ‘objective rationality’ in complex organizations, Child’s (1972) call for ‘strategic choice’ in understanding organizational contingencies, and the more recent work of Mintzberg (1994) on ‘strategy as craft’. However, the most influential recent exponent of a contextualist approach within the organizational and strategic change fields is undoubtedly Pettigrew (1987, 1997). His programmatic intent is to create ‘theoretically sound and practically useful research on change’, that explores the ‘context, content, and processes of change together with their interconnectedness through time’ (Pettigrew 1987: 268). This was conceived as a direct challenge to ‘ahistorical, aprocessual and acontextual’ approaches to organizational change; especially planned change approaches, managerial ideals of control, and the variable-centred paradigms of organizational contingency theories. Moreover, Pettigrew appeared to create a new strategic change–strategic choice variant of contextual analysis that can be characterized as incrementalism with transitions; an approach that sought to pragmatically accommodate both continuity and discontinuity in organizational change processes.

Dispersalist discourses locate agency as a decentred or distributed team or group activity of self-organizing learning, operating outside conventional hierarchical structures or control systems, and this allows organizations as complex systems of learning and knowledge creation to cope with innovation as well as the challenges of increasing organizational complexity, risk and chaos.

There is an enormous and increasing variety of dispersalist discourses, from notions of organizational learning and ‘sensemaking’ agency to complexity theories of agent-based interactions in ‘complex adaptive systems’ (Anderson 1999; Weick 1995). At the heart of many of these discourses is the idea of leadership and agency, organizational change and development as decentred or distributed team processes. These are certainly not new ideas, but their significance has grown enormously over the past two decades (Gronn 2002). There are a number of factors that partly explain this development. The reduction of central hierarchical control in organizations has resulted in a growing emphasis on project and cross-functional teams as mechanisms to achieve greater horizontal coordination across organizational divisions, units and work processes. This is also associated with a shift towards information-intensive and network organizations with ‘distributed intelligence’, creating new opportunities for knowledge creation and innovation at multiple levels (Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). In addition, the emergence of flexible forms of manufacturing and supply chain management founded on flexible ‘economies of scope’, rather than Fordist economies of scale has allowed greater potential for decentralized decision-making. It is against this background that Castells (2000) has provided a powerful and often positive overview of the tensions between hierarchies and networks, centralizing and decentralizing control in the emergence of new network organizations and societies. Others have, however, viewed the restructuring of managerial control negatively: ‘the dispersal of management away from managers entails no more than a dispersal of instrumental rationality’ (Grey 1999: 579).

Constructionist discourses abandon subject–object distinctions and the corresponding agency–structure dichotomies; there are no objective scientific observers or autonomous actors, but only socially constructed worlds of fragmented cultural discourses, practices and fields of knowledge in which the possibilities for ‘embodied agency’ and organizational change are fundamentally problematic.

Constructionist discourses are enormously diverse, partly because of their embrace of epistemological ‘perspectivism’ and their multiple points of intersection with the various intellectual movements of ‘poststructuralism’ and ‘postmodernism’. This makes it almost impossible to disentangle the various strands of constructionist discourses (Gergen 2001a). There are, however, at least four concerns that help define the programmatic intent of constructionism:

Anti-rationalism. Most forms of social constructionism are hostile to the claims of reason and rationalism, both as a foundation for knowledge of the world of things and as a guide to human conduct. Constructionism argues that rationalism is neither a foundation of truth nor a basis for self-knowledge, moral conduct or political emancipation; it is simply one discourse among many.

Anti-scientism. Constructionism holds that the ‘laws’ or ‘facts’ of the natural and human sciences are constructions within discourse that could be otherwise. Science is not a cumulative or progressive understanding of ‘how the world is’, nor does its knowledge of laws or facts predetermine how the natural or human sciences will evolve (Hacking 1999).

Anti-essentialism. Constructionists hold that there are no essences or inherent structures inside objects or people. Just as nature is not immutably fixed by entities designated as ‘atoms’, ‘cells’ ‘molecules’, so human subjects are not predetermined objects with discoverable properties such as ‘human nature’, ‘intentionality’, ‘free will’ or ‘personality’. These nominalist entities do not have an existence outside of socially constructed discourses.

Anti-realism. Constructionalists deny that the world has a fixed or predetermined reality discoverable by empirical observation, theoretical analysis or experimental hypothesis. There can be no truly objectivist or realist epistemologies founded on the subject–object and appearance–reality dichotomies that have characterized the history of Western rationalist thought.

These statements (minus any hint of invective) represent very broad meta-theoretical characterizations of constructionist positions. As such their implications will vary enormously in relation to the disciplinary fields, research traditions, or theoretical perspectives within which they are developed. Nevertheless, these statements broadly indicate that most constructionist discourses are compatible with the long tradition of relativism and nominalism in Western philosophy (Hacking 1999: 83).

While the four discourses are defined as ‘pure types’, they assume a multiplicity of forms, some of which may overlap with apparently competing discourses. For example, the shift within the OD tradition towards the concept of the learning organization has meant that its parameters overlap with dispersalist discourses; in this sense ideas of planned organizational change and system-wide organizational learning are often reinforcing. Similarly, contextualist discourses can be defined by ‘emergent’ or ‘processual’ perspectives, which may blend into ad hoc appropriations of constructionist ideas, especially if they are identified with a process ontology of change as becoming and ideas of knowledge as discourse. Ultimately if one pushes contextualism too far from its comforting empirical anchorages it can become constructionist.

Discourses are, of course, by their very nature enormously complex (Alvesson and Karreman 2000). They range from the apparently contextfree textual and conversational analysis of meaning to context-specific micro or macro discourses of ‘power/knowledge’ within discursive practices that may be critical or interpretative (Foucault 1994, 2000). It is not possible or necessary to examine all these forms of discourse. Here the primary focus is on disciplinary discourses that address issues of the role of ‘agency’ in organizational change. Disciplinary discourses are broadly defined as forms of language, meaning and interpretation representing and shaping relatively coherent social, cultural or disciplinary fields of academic knowledge creation and practice that embody contextual rules about what can be said, by whom, where, how and why. Disciplinary discourses are therefore forms of ‘rarefaction’ designed to limit or exclude those who cannot speak authoratively (Foucault 1994).

This definition emphasizes the plurality of disciplinary discourses, but it does not assume that all that exists are discourses about discourses (Foucault 1991). Many ‘scientific’ discourses may be characterized by patterns of self-referential circularity and indeterminism; and constructionists are right when they claim that: ‘there are no claims to truth that can justify themselves’ (Gergen 1999: 227). But this does not mean that ‘truth’ is ‘simply rendered irrelevant’ to discourse. Disciplinary discourses of knowledge ...