- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Asian Emperors

About this book

Much has been written about the rise of the Asian economies in recent decades, and their coming economic dominance in the next century. The New Asian Emperors shows how and why overseas Chinese companies are achieving dominance in the Asia Pacific. In the wake of the Asian Currency crisis, this book takes a fresh look at the role of the overseas Chinese as they continue to create some of Asia's most wealthy and successful companies.

In particular, the authors tackle the principal difference between Western and Eastern business practices. The overseas Chinese, due to their origins and history developed a unique form of management - now they maintain it as their competitive advantage.

Although Asian governments are currently floundering, the overseas Chinese networks continue to prosper. The authors explain the following to Eastern and Western managers:

the sources and characteristics of overseas Chinese management,

how to combat the overseas Chinese,

the strengths and exploitable weaknesses of the overseas Chinese,

whether overseas Chinese management practices will spread in the same way as Japanese management did,

whether Western management technologies will find themselves outclassed.

A feature of the book are the exclusive, in-depth interviews with the New Asian

Emperors since most of them avoid the press and little is known of them.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

The Foundations of Understanding

Chapter One

An Introduction

‘One generation passes away, and another generation comes; but the earth abides forever…. That which has been is what will be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.’Ecclesiastes

The above statement summarizes the history of the Overseas Chinese and the Chinese merchant classes. The Chinese merchant classes struggled against periodic campaigns of persecution in China to gain prosperity and their dreams of a good life for their families and children. The Overseas Chinese merchants struggled against periodic campaigns of persecution in their various new homelands to gain prosperity and their dreams of a good life for their families and children; and today, the Overseas Chinese struggle against periodic campaigns of persecution in many of their present homelands to gain their dreams of prosperity and a good life for their families and children. Though our book focuses on the corporate giants of the Overseas Chinese, we emphasize that the great majority of the Overseas Chinese who must face the travails of their people are not the super-rich Overseas Chinese of Asia, but those Overseas Chinese who are still struggling and basically, ‘fighting the good fight’.

The Overseas Chinese, contrary to what the name would imply, do not form one people, but groups of diverse people. Like the mainland brethren they left behind, they differ by regional/cultural and linguistic groupings to a much greater degree than most US-born American citizens do, and almost as much physically as Americans do. Like the other great imperial populations of the latter twentieth century, Russia and the United States, the Chinese people, and particularly their overseas populations, have shown a great proficiency in creating and accumulating wealth when their governments permitted them to do so. This combination of courage, skills, and intelligence has created something which most of the Chinese emperors of the past passionately avoided, an overseas colonial empire. The colonial empire does not constitute the traditional political empire of old, but appears more akin to the economic empire which many accuse the United States of building. In some few instances such as Singapore and Taiwan (we will speak of Taiwan as an autonomous state although the mainland Chinese government considers it a province) the Overseas Chinese serve as this empire’s political barons; but in every instance, they dominate as the commercial emperors of this New Asian Empire.

Westerners frequently view the Chinese people as one homogeneous population; and the Chinese as always having been under the sway of an all-powerful central imperial bureaucracy until the arrival of the Europeans. Neither of these two beliefs holds true. The Chinese people constitute a diverse population of different religions, different sub-cultures and different ethnic groups. Western China contains one of the earliest known, and best preserved burial sites of a Caucasian population anywhere in the world. The local population in the region continues to manifest some physical characteristics, for example, lighter, brown-colored hair and freckles, more frequently than the norm for other Asian populations.

Frequently, the Chinese Empire formed an empire in name only. Warlords from different areas would rise to challenge and sometimes to supplant the center. Invaders would breach Chinese defenses and create their own empires, introducing elements of their own cultures as they assimilated into the Chinese population. The center would collapse and China would break down into warring realms of various sizes and power; and frequently, the provinces would simply ignore the center’s directives.

The merchant classes of the southern coastal regions would most frequently ignore the center’s directives. These southern, coastal people dominated the various waves of Overseas Chinese who emigrated from China over the centuries. When the Chinese emperors periodically tried to block overseas commerce, contacts and emigration, the Southeastern Chinese provinces continued to press forward with their trading and emigration to wherever opportunities seemed to abound. In efforts to stop international trade and contacts, various Chinese emperors have embarked on the following prohibitive measures (this is a very short and incomplete list):

- In 1424, the Ming emperor, Hung-Hsi, banned foreign expeditions of any kind and scuttled an imperial fleet to emphasize his point.

- In 1661, the Manchu emperor, K’ang-hsi banned travel and evacuated coastal regions of China to about ten miles inland.

- In 1712, K’ang-hsi requested foreign governments to repatriate Chinese emigrants so that they could be executed.

- From 1717 until his death, K’ang-hsi tried once again and initiated a ban on travel. The emperor died in 1722, but his successors continued trying until 1727 when they lifted the ban after ten years of dismal failure.

- In 1959, Mao Tse-tung tried a new tack by calling on the Overseas Chinese to return home. Of the many millions of Overseas Chinese, Mao’s ships picked up 100,000 seeking to come home.

In 1911, the Overseas Chinese communities finally responded in kind to the Manchu dynasty’s many punitive campaigns and policies against them and their mainland brethren: they financed Sun Yat-sen’s overthrow of the Manchus. The Overseas Chinese were, and remain, the epitome of capitalistic humanity.

The Overseas Chinese we have discussed and which form the focus of this book are these capitalist traders. Though people generally think of the Overseas Chinese as traders, other groups also make up the Overseas Chinese communities. Wang Gungwu (1991), in his book, China and the Chinese Overseas, discusses the four different patterns of Chinese migration. He identified the four patterns as:

- The trader pattern

- The coolie pattern

- The sojourner pattern, and

- The descent or re-migrant pattern

The trader pattern

The trader pattern represents those Chinese of commercial or professional classes who went overseas for reasons of business or employment. These people usually worked for their personal benefit or for domestic Chinese businessmen’s benefits, usually, but not always, relatives of some sort. If their overseas efforts met with success, more relations and associates would follow and work to expand the businesses further.

The coolie pattern

The coolie pattern represents another group of Chinese who sought their fortune overseas. These individuals usually originated from the peasant classes, or were landless laborers, or the urban poor. They went overseas on labor contracts and many returned to China when their contracts came to an end. Many, however, stayed to build their fortunes, and their futures, in their new homes. This pattern has supplied the bulk of today’s Overseas Chinese population.

The sojourner pattern

These members of the Overseas Chinese communities left China to act as representatives of the Chinese culture and way of life. They appeared during a period of time when Chinese governments were trying to re-exert their control over the increasingly wealthy Overseas Chinese communities. The sojourners perceived their duty as lobbying local governments for the rights to establish Chinese schools to educate the children of local Chinese in the Chinese language and in accordance with Chinese customs. They also sought to encourage local Overseas Chinese to remain faithful to their culture and country, and importantly, to their government.

The descent or re-migrant pattern

Growing numbers of Overseas Chinese do not speak the Chinese language, have never set foot in China, and have even emigrated from the countries in which their ancestors originally settled. These ethnic Chinese, socially and frequently even culturally, form members of their local national societies in every way imaginable.

Though we focus primarily on those Overseas Chinese who began to build their fortunes as merchants, the greatest number of today’s Overseas Chinese commercial aristocracy in Southeast Asia descended from people who fit into the coolie and sojourner patterns. Regardless of which pattern the present-day Overseas Chinese businessmen and women descended from, they form supreme business practitioners, resourceful and daring, yet rarely so daring as to be foolhardy.

Who are the Overseas Chinese?

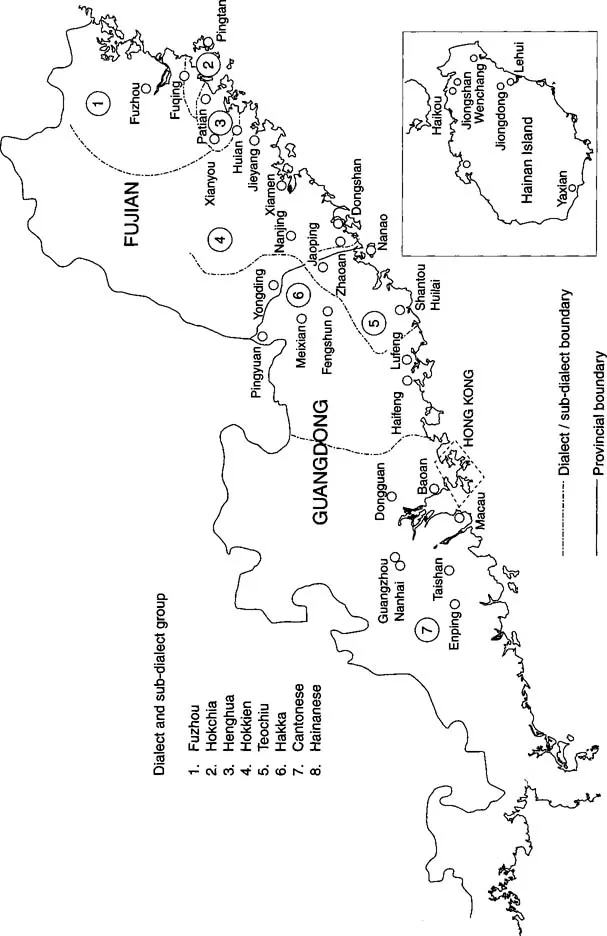

The bulk of Southeast Asians are, at least in part if not primarily, of Chinese origin (waves of Chinese emigration to the countries of Southeast Asia have occurred for literally thousands of years); yet, generally only those people migrating to Southeast Asia in the last one or two waves of migration are considered as Overseas Chinese. Most Southeast Asians considered Overseas Chinese arrived in their new homelands sometime in the latter years of the nineteenth century or in the twentieth century. Guangdong’s and Fujian’s coastal regions (to the immediate north and northeast of Hong Kong), as well as Hainan Island (between the Gulf of Tonkin and the South China Sea), dominated the last few waves of immigration. Figure 1.1 shows these coastal regions and the island. Eight primary groups of Chinese emigrated from these areas at this time (as enumerated by dialect and sub-dialect groupings) to the different countries of Southeast Asia.

Figure 1.1 Primary homelands of today’s Overseas Chinese. Adapted from East Asia Analytical Unit (1995)

They were the:

- Cantonese

- Fuzhou

- Hainanese

- Hakka

- Henghua

- Hokchia

- Hokkien

- Teochiu

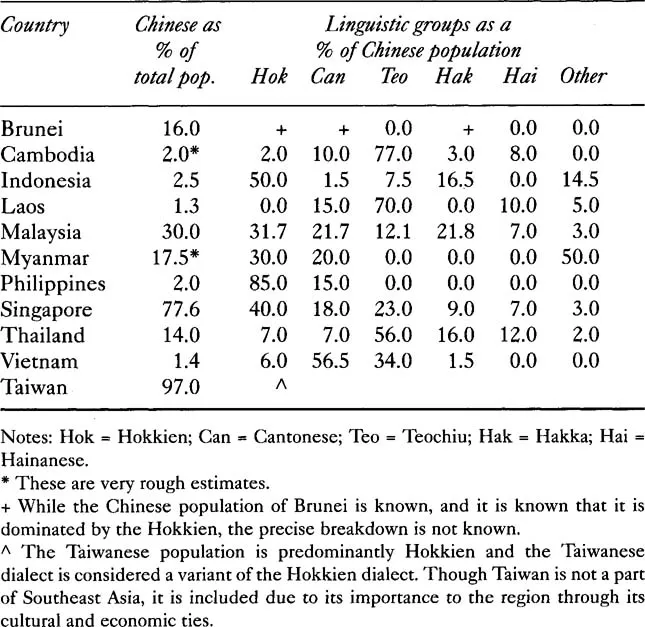

When the different groups left China, they tended to settle among their own people in the different countries to which they went. Hence, one or two of the above-mentioned Chinese communities tend to dominate the Overseas Chinese populations of individual Southeast Asian countries. One or two of the linguistic groups may also dominate particular trades and professions. Table 1.1 presents the breakdown of the Overseas Chinese populations of the various Southeast Asian countries. For two countries, Cambodia and Myanmar, the figures form estimates. During the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia, the Chinese, primarily city dwellers, suffered especially badly and reliable figures for their population do not exist. Myanmar has never released reliable figures on their Overseas Chinese population.

As Table 1.1 shows, the Hokkien and Teochiu people tend to dominate in most Southeast Asian countries. Historical and geographical reasons contribute to this dominance. Throughout its history, China has alternated between outward-looking expansionist regimes and inward-looking isolationist regimes. The Hokkien and Teochiu homelands lacked good farmlands, and possessed relatively good ports on their coasts. Their physical distance from the different historical Chinese capitals also allowed them to escape the center’s notice with the help of local authorities. Hence, under isolationist Chinese regimes that discouraged international trade and contacts, the Hokkien and Teochiu people could openly use their seafaring skills for domestic trade and fishing and had a substantial incentive to do so. Conversely, expansionist regimes that supported international trade also encouraged the Hokkien’s and Teochiu’s efforts to build trading relationships. Wealth would flow into these groups’ homelands through their presence in Chinese trading circles. When circumstances changed again, and isolationists dominated policy, the Hokkien and Teochiu could not surrender the prosperity they had

Table 1.1 The Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia

gained through trade, and circumvented the central authorities whenever and however they could. With only subsistence farming possible, trade with other regions within China served essential needs for these groups. They used their domestic trade and shipping, and their contacts in local and central governments, to cover their activities and to maintain their international trading presence. The manner in which their international trading presence evolved had several important effects on the manner in which the Overseas Chinese have historically conducted their business.

In Table 1.1, the large ‘Other’ category for Myanmar arises because the largest group of ethnic Chinese in this country originates from traditional homelands spanning the common border of Myanmar and

Admiral Cheng Ho

Patron saint of Chinese trade and internationalism

The Ming emperor, Yung-lo (reign 1402–1424) constituted the last of the truly internationalist rulers among China’s pre-communist rulers. The great admiral Cheng Ho served as the primary instrument of his international exploration and, to a limited extent, maritime imperialism. Cheng Ho was a eunuch of Mongolian ancestry and a Muslim who, during Yung-lo’s reign, led six great voyages (he made a total of seven). The voyages averaged two years in length, and recorded visits to thirty countries, including visits to Hormuz at the entrance to the Red Sea, and to Jeddah, on the west coast of the Arabian Peninsula. Cheng Ho’s voyages were not the sailing voyages of two or three lonely ships as were the European voyages of exploration; rather, they included major fleets with more than 20,000 men, upwards of sixty of the largest wooden capital ships ever made, with fleets of support vessels numbering more than 200 ships. During his trips, Ch...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Features

- Endorsements

- About the authors

- Acknowledgements

- Part One The foundations of Understanding

- Part Two The Foundations of Analysis

- Part Three The Implications for Business

- Bibliography

- Appendix A

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access New Asian Emperors by George Haley,Chin Tiong Tan,Usha C V Haley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.