music for voice

From earliest days young children use their voices with great versatility and expressive power. First babblings and cooings give way to playing with sounds and newly learnt words, making dramatic voice sounds as part of play and private sing-talking. Children discover the varieties of sound possible with the voice and are learning to use these to communicate, not just through speech but through all the vocal sounds, the small inflexions, the timings and changes in dynamic which run alongside speech.

So the young child arrives at school already practised at making voice-music. For the teacher here, in voice play, is a ready made starting point for making music with voices upon which to build. But one which is perhaps overlooked, and the teaching of standard songs, to quite large groups of children, very often comes to dominate in the early years of schooling. Singing is one important strand of musical experience but it is valuable to think of music with the voice in broader terms as a network of many kinds of vocal activity. This is, after all, in keeping with the way young children themselves use the voice. Indeed, learning to sing taught songs might be seen as an endpoint, something to aim for in early years music, rather than a starting point. Children arrive in school sometimes with very little prior experience of singing and will need much preparatory work in finding their voices and learning to pitch them. Varied vocal activity, spontaneous song singing, voice play and teacher-led games provide such opportunities for finding voice freedoms and practising.

The following list introduces the range of ways children might be involved in making music with the voice in early years schooling:

- voice play;

- joining in rhymes or songs;

- playing with words, rhyming;

- improvising and composing chants and songs;

- learning to sing songs;

- learning voice skills.

Where to start? First by discovering what children’s voice play and spontaneous singing sounds like; listening.

voice play

Taking time to observe children at play in an early years setting will reveal a wealth of voice play. Here are two observations and listenings transcribed from video recordings:

Kylie (3y 10m) sat on the floor, alone, engrossed in playing with a large scale train set. As she moved the train along the track she babbled syllable sounds in a quiet, high-pitched voice that climbed higher and higher. Next she chanted rhythmically the words ‘going through the tunnel’ several times over.

James (4y 2mo) played on the climbing frame outside, jumping up and down on the top platform. He called to a nursery worker, ‘you can’t get me!’ chanting on two notes. The teacher replied, matching the child’s call with a sung response. The calling back and forth continued for several turns. James became increasingly excited by the game.

In these examples, and many others like them, the teacher might notice children playing with word sounds and syllables, a continuation from babyhood babbling. Children sing-talk to themselves or make up on-the-spot chants which they sing repeatedly. The child’s voice play seems to be closely connected with movement; either the child’s own physical movement as he jumped up and down or the movement of a toy being sung along the track. It would be difficult to separate out the vocal play from the whole activity; the moving, the thinking and feeling.

Notice the roles taken by the teachers in each example. To have intervened and joined with Kylie’s solitary train play would have intruded. The teacher stood back, watched, listened and recorded the moment. In James’ case he was calling to the adult who joined in the game creating a spontaneous call and response sequence with him. In both examples the intervention was carefully matched in response to the child’s contribution.

The child’s interest in spontaneous singing will be sustained by verbal and non-verbal responses of the teachers around. Eye-contact, facial expression and gesture adds to the special quality of listening to children. A comment will acknowledge that the voice activity has been listened to and can describe back, helping the child to become aware on a different level of their own voice play and how it has sounded to others.

In research carried out by Tarnowski (1994) she explored the effects of different styles of teacher intervention upon the voice play of young children in a nursery. Those children who had been supported by an ‘observer’ who was attentive and provided verbal feedback but no form of direct instruction later showed much more variety and inventiveness in their voice play than other groups whose teachers had adopted a more directive role.

joining in with rhymes and songs

The teacher may initiate vocal play by playing voice games, improvising song play or singing known songs with and for children. This might be spontaneous on the part of the teacher, to capture a moment or to accompany a routine, or it might be part of the planned day, to sit on the carpet for singing with a songbook just as one might be available for story reading. Puppet play in which the puppet sing-plays with the child (see page) can be particularly successful in encouraging young children to find their singing voices (Suthers, 1996).

The youngest children are probably not ready to take part in formal group singing experiences but will cluster around anyone who looks ready to play. The teacher models singing and other voice play for the child and provides opportunities for them to listen attentively and take part in whatever way they are able. Children often begin by joining in with just a fragment of the rhyme or song and by taking part in game actions and rhythmic movements. Taking part is the essence so that singing is primarily a sociable experience.

This one-to-one interaction between teacher and child enables the teacher to notice and build upon the child’s contribution, introducing small step by step challenges in a playful but guided situation.

The teacher might observe whether the child can:

- listen attentively;

- respond with eye contact and facial expression;

- produce a range of vocal sounds;

- find their singing voice;

- join in with fragments of the song or rhyme;

- take part in game actions or rhythmic movement.

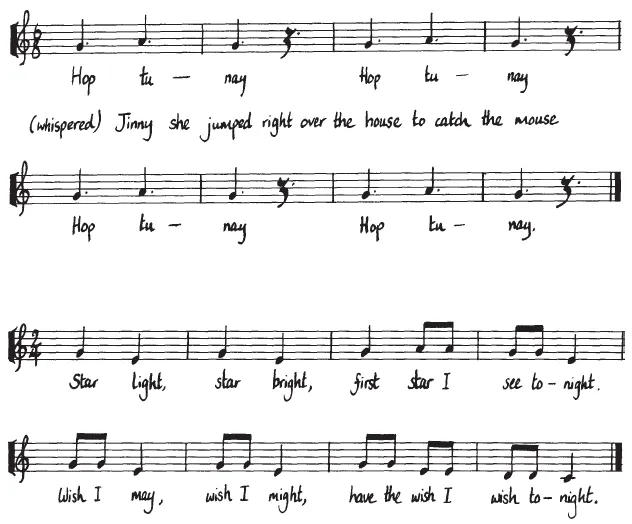

one-liners

Many first ‘joining in with’ songs are chant-like one-liners which sit somewhere on the borderline between speech and song. Teachers may make such songs out of often repeated classroom instructions (Flash, 1990) such as ‘clearing-up time!’ or ‘come and sit on the carpet’. In this way small songs emerge from and become part of the fabric of daily classroom life.

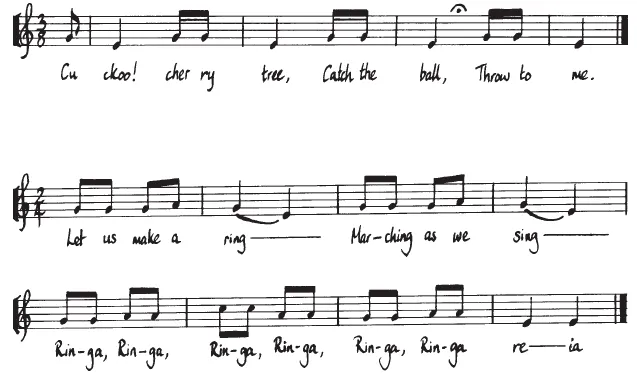

Here are four songs for first singing:

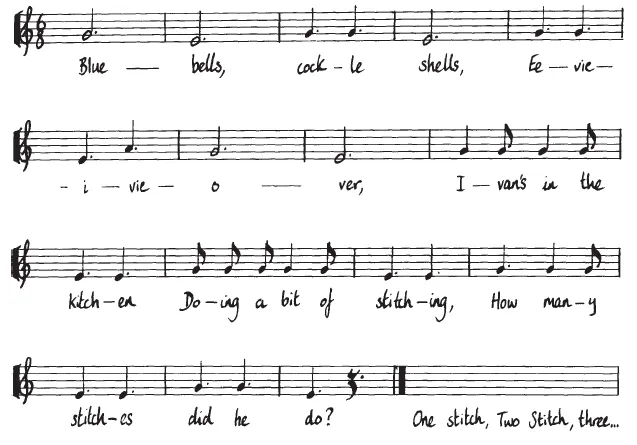

joining-in song: Bluebells, Cockle Shells

Childhood has its own songs, baby and toddler lullabies, bouncing games, jig-jog ditties and tickling rhymes; songs which are sung by adults for young children to take part in. Older children out playing have traditionally had their own singing games. This is an English skipping game in which the challenge is to see who can do the most ‘stitches’ or skips. The game is adapted for teachers to sing for and with the youngest children to encourage them to take part.

Hold both hands with a partner. (Teachers should offer children just one finger for clasping so that the child can release the grasp when they wish.) Swing both arms gently from side to side in time to the song. When it comes to ‘stitching’ mark out the counting with a downward bounce of both hands. The children decide how many stitches to count out each time. Children will have their own names for their primary carers, substitute these for each child in turn.

- each child’s response to joining in with others;

- how each child joins in with voice (or not);

- how each child moves, level of coordination and control.

- if joining in with singing, how their voice pitching matches the song;

- if joining in with movement, whether the child is swinging to a regular tempo.

In this song the teacher might partner children in turn and adjust the singing each time to the new child’s contribution. Careful observation will tell the teacher just what support the child needs.

When children are able to join in with singing confidently new challenges are set:

- changing the pitch of the song, higher or lower;

- the tempo of the arm sway is changed and the singing becomes faster/slower;

- the dynamics are varied, sung quietly, louder or with variations of dynamics.

playing with words and rhyming

There is music in language. Creating an early years environment rich in rhymes, poems, chants, riddles and word games, drawn from a range of oral traditions, is not only valuable for laying the foundations of language learning (Whitehead, 1996) but for music also.

Patterns of words can be taken from songs and spoken rhythmically.

For example:

eevie ivie

eevie ivie

eevie ivie

over—

—perhaps repeated in sequence and said with many different voices, whispering, shouting, growling, squeaking and so on. Opportunities to discover and try out different voices are important for developing vocal freedom and variety. The one-liner chant (see above) ‘Hop tu nay’ combines singing with whispering and requires the children to change quickly from one to the other. Children can be encouraged to play around with their voices, ‘Can you wobble it, stretch it, twang it, slide it?’ (Victor-Smith, 1996).

Rhyming activities offer opportunities to explore the musical elements; where the accents fall, steady beat and metre, rhythm patterning and silences. For example, this well-known rhyme:

One potato

two potato

three potato

four—

five potato

six potato

seven potato

MORE! —

—has a skipping rhythm throughout but a silence after ‘four’ and ‘more’. The repetition builds towards the climax on MORE! The rhyme can get louder and louder, or start loud and become much quieter and end with a surprise shout and clap on the MORE! The possibilities for variation with such simple materials are endless. The inventiveness will come from the children who can be given the opportunity to offer their own versions.

The next chanting game is more suitable for older children. The rhyme has a vigorous, syncopated rhythm to it which is picked up in the strong consonants of the words ‘Kourilengay, Kalengena’.

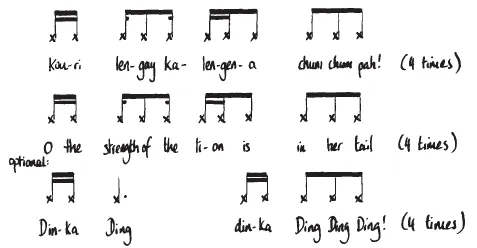

children’s chanting game from Tanzania: Kourilengay Kalengena

The children process, conga style, and stamp three times on the ‘chum chum pah!’. Think of dance in the African way, that the dancer is a drummer with the ground for a drum.

Children then stand and chant rhythmically the phrase ‘O the strength of the lion etc.’ and one child improvises a lion dance.

Different animals are chosen for the next verses and where the strength lies must be decided. (Be sure to alternate gender for animals.)

The chant ‘dinka ding’ is a kind of vocal percussion and should be spoken with lively rhythm and clear diction. These are the word sounds given in the rhyme, but the children could invent their own vocal percussion from short rhythmic sound words.

improvising and composing

Young children readily make up their own songs as part of all kinds of play. In the early years the differentiation between song and speech is hardly marked. Later children gradually separate out the two kinds of voice use and singing becomes limited to a particular and intentional kind of activity. Unfortunately, teachers often reinforce this separation earlier than necessary, sometimes even discouraging singing either directly as ‘being noisy’ or indirectly by negative attitudes or modelling. The initial readiness children have to use song as a quite normal medium of expression can be built on as a basis for improvising and composing songs.

Composing with the voice has the substantial advantage that children can tap directly into their musical sense, without the difficulty of managing to control sound produced externally on an instrument. In most cases they also have substantial direct experience of hearing and singing songs, which is not paralleled in instrumental music. The connection of language use and vocal music adds a further dimension at a stage when children are particularly sensitive to the intonation and rhythms of speech. As a result of all this, children’s early song compositions are usually much more advanced musically than their instrumental pieces (Glover, 1993).

spontaneous song making

Coral Davies (1986) notes how a spontaneous song sung by a 3-year-old reveals ‘how much music she has already absorbed from her experience in the nursery and at home’. Children’s songs draw on asp...