![]() Part I

Part I

Singular Journeys![]()

1

Lucio Costa’s Luso-Brazilian Routes

Recalibrating “Center” and “Periphery”

Gaia Piccarolo

Rhetoric concerned with identity-building and the relationship with European culture in terms of “periphery” versus “center” is one of the leitmotivs of Latin American architectural historiography. Facing the demand to mediate between local, national, and international levels, categories like regionalism, nationalism, and Pan-Americanism entered the architectural debate from the first decades of the twentieth century, in response to the search for a recognizable identity.

Lucio Costa, a key protagonist of these debates, worked strenuously in order to better define Brazilian particularities.1 While he is currently portrayed as striving for a synthesis between modernity and tradition, international and national architectural languages, less known is his contribution to the forging of relationships and exchanges between Brazil and its former colonizer, which deserves further investigation on the basis of its economic, political, and diplomatic dynamics, and as an example of the circulation of ideas and models across the Atlantic. This chapter explores the reciprocal influences between Brazil and Portugal across their routes to modernism, especially through Costa’s personal contribution to the development of Luso-Brazilian relationships. In the process, the dynamics of “center” and “periphery” are brought into question, pointing out the specificity of this case study due to its peculiar historical developments and motivations.

Costa undertook his first study trip to Portugal in 1948—from a supposed peripheral condition in Brazil—in order to understand the process through which Brazilian tradition had developed from the center of its source.2 Yet Portugal was already looking at Brazil as a new center for architectural innovation: five years earlier, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, had held its seminal exhibition on Brazilian architecture, whose accompanying catalogue, Brazil Builds circulated in Portugal, as in the rest of Europe, spreading expressive images of Brazilian architectural production.3 It is worth noting that this process inverted that of the first decades of the twentieth century, when the Portuguese legacy was a main topic of discussion during Brazil’s passionate “anthropophagic” search for its own cultural roots, led by poet Oswald de Andrade, and when the migration of Portuguese intellectuals to Brazil continued to bring to the former colony ideas and issues from contemporary Portuguese debates.

This was the case with the engineer Ricardo Severo,4 the main person responsible for the recovery of the Portuguese legacy in Brazil and for the importation of the debate on the “Portuguese house,” led in those years by the traditionalist Portuguese architect Raul Lino, whose articles circulated in Brazilian architectural periodicals during the 1920s.5 The young Costa played an active role in the traditionalist movement in Rio de Janeiro, mainly through his personal and professional contacts with its leading figure José Mariano Filho,6 whose research was focused on the formulation of a model of the “Brazilian house” inspired by domestic architecture of the colonial period. This effort was part of the search for an “authentic” and “national” architectural expression that derived from a widespread discomfort with nineteenth-century eclecticism and French-based academicism.

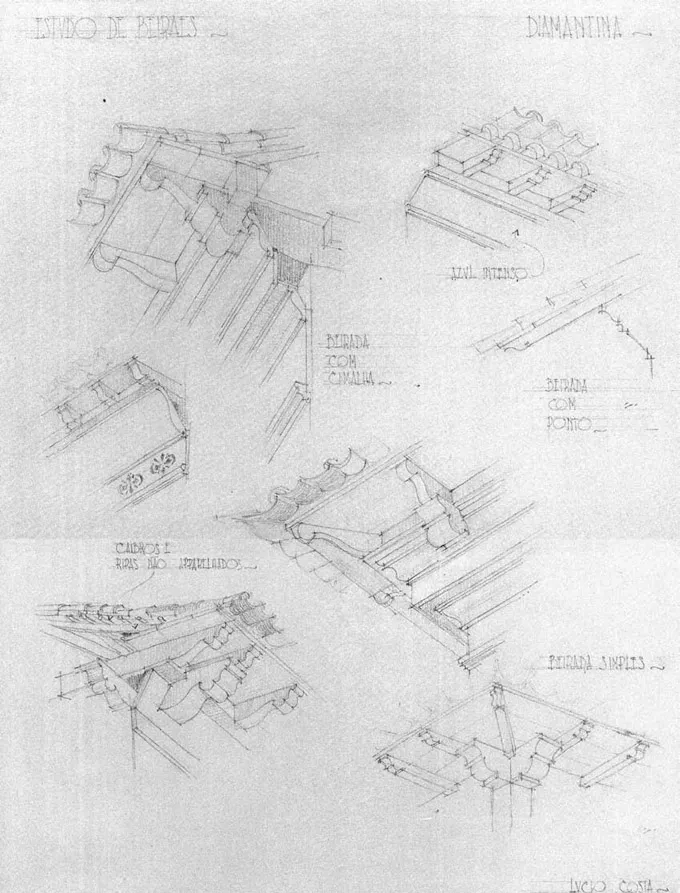

In 1924, within the framework of a renewed and wider interest in national historical heritage,7 Mariano Filho sponsored Costa to undertake a trip to Diamantina, a colonial city in the valley of Minas Gerais, in order to study its architectural heritage; on Costa’s return he observed in an interview how he had been deeply touched by the contact with vernacular colonial domestic architecture.8 The drawings produced show a careful and technical-focused survey of authentic traditional architectural and constructive solutions, intended for collecting a sort of repertoire for use in current design practice.9 After all, Costa’s architecture in the 1920s was perfectly placed within the diffuse traditionalism whose circulating models nationalized Beaux-Arts composition through the incorporation of colonial decorative motifs.

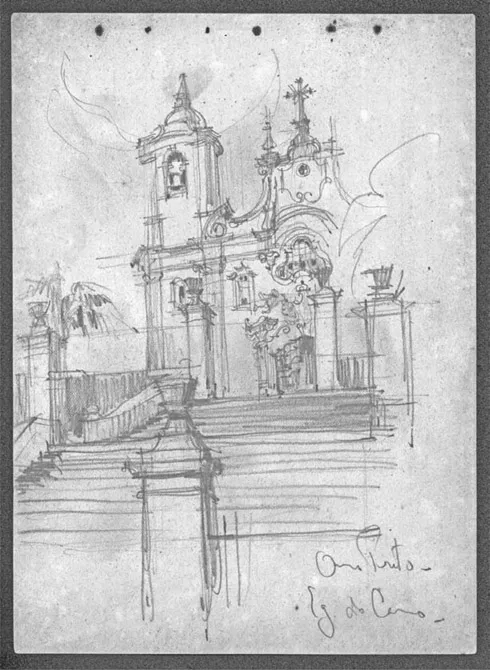

Some years after this first mission, on returning from a study trip to Europe (1926–1927), Costa was in Minas again, visiting Caraça, Sabará, Mariana, Ouro Preto, and going back to Diamantina. This time free from any specific commission, he immortalized several monumental buildings in their historical sites, fixing on paper architectural details, furniture pieces, even landscapes with passionate accuracy and a charming pencil stroke.10

At this precise moment, the sociologist Gilberto Freyre, one of the main theoreticians of Portuguese influence on Brazilian identity in the complexity of its cultural manifestations, was promoting the ideal of a “national unity under regional variety,”11 a theme that also motivated Costa’s 1929 text: “O Aleijadinho e a arquitetura tradicional.” Despite his skepticism concerning the refined and decorative expression of the artist from Minas, Costa’s essay asserted that upon examining the national architectural heritage, one comes to realize that “Brazil, despite its extension, its local differences, and other complications, had really to be one thing. Good or bad, it has been shaped all-in-one, by the same spirit and by just one hand.”12

This mix between nationalism and the emphasis on regional specificities was one of the many points where the aims of intellectuals and the government converged at this moment in Brazil. A revolution in 1930 established the first regime of Getúlio Vargas (1930–1945, 1951–1954), marked by a strong centralization of the state, an aggressive nationalism, and a push toward modernization. Within the soft renovation of cultural institutions promoted by the new government, modernist intellectuals who were engaged with the Vargas administration called upon Costa to lead the School of Fine Arts, a post that he held for less than one year, and that inaugurated his modernist militancy in relation to local artistic and architectural debates. Over the following years he became deeply involved in the dissemination of modernism and of the ideas of European modernist architects— a process culminating with his coordination of the project for the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro.

Costa’s new distance from the ideological and aesthetic positions of the traditionalists became evident in a meeting with Portuguese architect Raul Lino, who, when visiting Brazil in 1935, insisted on being introduced to the man whom he characterized as a “true mentor of the young Brazilian architects.”13 In Lino’s retrospective reconstruction of their dialogue, mainly afforded through quotations

1.01 Lucio Costa, drawing of Aleijadinho’s Igreja do Carmo, Ouro Preto, Brazil, 1927

from Costa’s text “Razões da nova arquitetura,”14 he affirmed—partially mystifying the truth yet stressing well the overwhelming distance between their positions— that his “distinguished colleague … doesn’t want to hear about tradition,”15 but rather approached problems from a strictly Functionalist point of view.

Meanwhile, the first Vargas government was marked by efforts at rapprochement with Portugal, further emphasized after Vargas’s authoritarian turn in 1937 with the institutionalization of the Estado Novo (New State), modeled on the Salazar regime in Portugal (1932–1968).16 The creation of the Serviço do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (SPHAN) in the same year, represented an important instrument of the government’s cultural strategy to establish stronger relationships with the former colonizers within the framework of Brazil’s affirmation as a world power.

Under the sponsorship of the Ministry of Education and of SPHAN, several modernist intellectuals were involved in building a theoretical definition of a

1.02 Lucio Costa, studies of eaves in Diamantina, 1924

“national tradition” on which the selection of the historical sites to be physically safeguarded would be grounded. Costa’s involvement with this organization was a turning point in determining the direction of his interests in the following years, resulting in the definite development of a personal modern syntax that synthesized a local and vernacular vocabulary.17

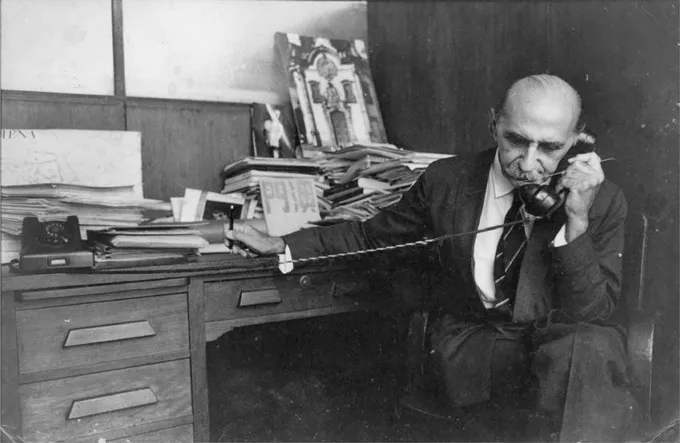

1.03 (above) Lucio Costa at the Serviço do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (SPHAN)

1.04 Lucio Costa, Park Hotel São Clemente, Nova Friburgo, Brazil, ca. 1948

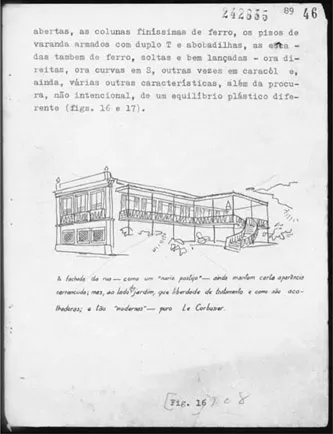

1.05 Lucio Costa, sketch for the text “Documentação necessária,” 1937—a solution defined as “pure Le Corbusier”

1.06 (below) Lucio Costa, Museu das Missões, São Miguel das Missões, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, ca. 1940

His article “Documentação necessária,” published in 1937 in the first issue of SPHAN’s official journal, returned to the theme of the colonial house.18 However, the protagonist was now its direct progenitor, the architecture of the “good Portuguese tradition,” together with the “old Portuguese master builder of 1910” who, in Costa’s opinion, was able to instill in his works a “perfect plastic health” and a “typical Portuguese carrure [build or stature].” Costa also mentioned the importance of studying the vernacular Portuguese house in order to “take advantage of the lessons of its more than three hundred years of experience,” which, in one of the illustrations, he defined as “pure Le Corbusier” due to the modernity of its architectural solutions.

Within SPHAN, Costa became involved in day-to-day work on the historical heritage of Brazil, starting with a field study of the ruins of Sete Povos das Missões in Rio Grande do Sul, the result of which was the little museum he designed in order to preserve the site’s archeological remains. Although its horizontal tile roof and open arcades—whose columns incorporated capitals and materials found in situ—were clearly inspired by old colonial houses, the steel-and-glass Miesian box containing the archaeological finds allowed them to be perceived as part of the landscape and gave a decisively modern tone to the whole intervention.

At the same time, he published articles addressing questions such as the evolution of Luso-Brazilian furniture and the architecture of the Jesuits in Brazil, as well as several historical essays on Aleijadinho, in which he retreated from his earlier skepticism.19

Considering the body of Costa’s written work in this period and his untiring promotion of Oscar Niemeyer, it is easy to discern a theoretical formula aimed at creating an ideal bridge between different and distant experiences in order to prove the existence of a unique “national personality.”20 On one side, the unselfc...