1 Introduction

1.1 Preamble

The Earth has never been characterised by a constant, static environment; environmental change has been the norm rather than a rarity throughout the c. 5000×106 years of Earth history. On both a temporal and spatial basis, the rate of change has varied, with long periods of gradual and subtle transformation punctuated by major upheavals. The study of Earth history has developed in a similar way, with periods of consolidation following the acceptance of major theories.

Environmental change has also been rhythmical in character because of the influence of regular fluctuations such as the revolution of the Moon around the Earth and the revolution of the Earth around the Sun. Such fluctuations influence the pattern of tidal frequency and seasonality. The Earth experiences additional oscillations which are cyclical, e.g. the recurrence of phenomena such as mountain building or climatic change generated by the periodicity of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun (the Milankovitch hypothesis—see Section 2.4), which have occurred throughout geological time.

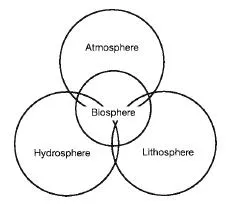

Figure 1.1 The relationships between the lithosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere and biosphere

These and all other aspects of Earth history have influenced, and been influenced by, life. The manifestation of this relationship is the operation of biogeochemical cycles whereby, as is implied by the term, chemical exchanges occur between the compartments of the Earth (the lithosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere and atmosphere, Figure 1.1) and are mediated by living organisms that comprise the Earth’s biota. Consequently, environmental change can be expressed in terms of adjustments in global biogeochemical cycles. Such changes have been ultimately associated with climatic change throughout Earth history, especially in relation to the carbon, nitrogen and sulphur cycles.

Only in the last 200 years has the idea of a dynamic Earth been in vogue. Theories concerning plate tectonics, the geographical cycle, glaciation, environmental systems and Gaia have been developed since 1850. Concomitantly, major advances have been made in field and laboratory methods which now encompass a wide range of sedimentological, biological and stratigraphic techniques. The advent of absolute dating techniques since the 1950s, when radiocarbon dating was first established, has considerably improved the precision of studies of environmental change, and has facilitated the determination of rates of change. In addition, access has been gained to hitherto inaccessible archives of information on environmental change, notably ocean sediments and polar ice. Research has also extended into remote regions such as Antarctica and high mountain regions, as well as high and low latitudes.

Interest in environmental change has intensified in the last two decades because of the focus on environmental issues such as global warming, acidification and stratospheric ozone depletion, all of which have received considerable media limelight. Such issues are no longer only the concern of scientists and academia. On the one hand they concern every member of society, and on the other hand their mitigation or control requires planning, financial assistance and expertise which involve local, regional, national and international political involvement. This reflects the close relationship between even the most technocentric members of society and the environment, as well as the interconnectedness of people, their resource use and the wider environment.

There is abundant evidence for human-induced environmental change at all scales, from the local to the global, and a growing recognition that mitigation strategies are essential to restore or preserve the status quo. Consequently, research into past environmental change, particularly that which has not been anthropogenically driven, is of considerable importance in order to obtain baseline data on natural change and rates of change. Moreover, and especially in relation to climatic change, society requires the capacity to plan for the future, i.e. to have an accurate predictive capability. One aspect of developing such a capacity is to generate models, e.g. General Circulation Models, whose accuracy can be evaluated to a degree by using them to simulate past natural environments. Recent natural environmental change has thus become the subject of intense investigation, especially that which has occurred in the last 3×106 years or so. This encompasses the Quaternary period, which is the most recent geological period coming right up to the present, and the final part of the earlier Tertiary period. The particular significance of this time interval is the repetition of periods of cold which, in the later part of the Quaternary period, were sufficiently intense to become ice ages separated by warm intervals known as interglacials. The natural environmental changes of the last 3×106 years are the subject of this book.

1.2 A synopsis of the development of ideas on environmental change

Ideas about environmental change have altered considerably in the last 200 years, as is reflected in the chronology given in Box 1.1. Prior to 1800, views on Earth history were dominated by the proclamation of Archbishop Ussher of Armagh in 1658. This invoked the formation of the Earth as occurring in 4004 BC, a date derived from calculations based on Biblical genealogies. A major advance came in the mid-1800s when the glacial theory was inaugurated (Emiliani, 1995). The latter was a seminal idea that represents the foundation of modern-day Quaternary studies and which had profound repercussions for the Earth Sciences in general. The recognition of the significance of cycles of erosion and uplift (the Geographical Cycle discussed in Section 1.2.3) and the theory of Continental Drift also exerted considerable influence along with developments in the biological/ ecological sciences such as Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Together with advances in methodology and the investigation of an increasing range of natural archives of environmental data, tremendous strides have been made in recent years. New theories such as Systems theory and the Gaia hypothesis have also been spawned to provide frameworks for examining the many reciprocal aspects of environmental changes, including the role of humans. There is, however, still much to learn about the complex dynamism that characterises planet Earth.

Box 1.1

Some important theories, ideas and developments concerning Earth history and environmental change

| Date |

| 1 Archbishop Ussher’s statement that the Earth formed in 4004 BC. | 1658 |

| 2 Catastrophism dominated ideas about Earth history. | 1600s to 1850s |

| 3 The diluvial theory, reflecting the significance of the biblical flood, was invoked to explain the occurrence of specific landforms/deposits. | 1600s to 1850s |

| 4 The glacial theory was founded by Hutton. | 1795 |

| 5 Observations on contemporary glacial processes in Switzerland and Scandinavia provided evidence for the glacial theory. | early 1800s |

| 6 Lyell proposed that icebergs were responsible for the deposition of erratics, drift, etc. | 1833 |

| 7 Agassiz presented the glacial theory to the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences. This ensured the formal acceptance of the glacial theory. | 1837 |

| 8 James Geikie proposed the occurrence of four glaciations in East Anglia. | 1877 |

| 9 De Geer’s use of varves for dating. | 1880s |

| 10 Penck and Brückner proposed four-fold glaciation for the Alpine region. | 1909 |

| 11 Von Post’s publication of percentage pollen analysis. | 1916 |

| 12 Clements’s theory of plant succession published. | 1916 |

| 13 Milankovitch’s astronomical theory of periodic climatic change. | 1920s, 1930s |

| 14 Concept of the ecosystem established by Tansley. | 1935 |

| 15 Work began on ocean sediments. | 1950s |

| 16 Development of radiocarbon dating by Libby. | 1940s/1950s |

| 17 Adoption of the systems approach by environmental sciences. | 1960s/1970s |

| 18 Theory of plate tectonics developed. | 1960s |

| 19 Gaia hypothesis formulated. | 1972 |

| 20 First deep-polar ice core (Vostok) extracted. | early 1980s |

1.2.1 The glacial theory

Acceptance of Ussher’s statement fostered the philosophy of catastrophism, whereby Earth surface features were created by cataclysmic events. Consequently, the diluvial theory was developed to explain the occurrence of many geomorphological characteristics as products of the Biblical Flood. However, by the late 1700s, the Edinburgh geologists James Hutton and John Playfair were questioning the validity of this approach. Instead, they advocated that present-day Earth surface processes could be invoked to explain the formation of landforms, and so the principle of uniformitarianism was established. This approach was further emphasised by Charles Lyell’s promotion of the present as the key to the past. Moreover, Hutton’s observations on erratic boulders in the Jura Mountains caused him to implicate glacier ice as the mechanism for transportation. It was in 1795 that Hutton laid the foundation of the glacial theory.

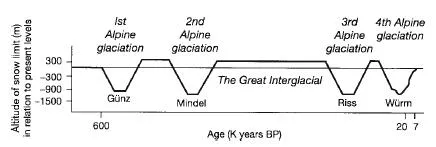

However, it was not until the 1820s that the glacial theory gained wider acclaim on the basis of work in the Swiss Alps by Jean-Pierre Perraudin, a mountaineer, the naturalist Jean de Charpentier, and Ignace Venetz, a highway engineer. They proposed that Swiss glaciers had once been more extensive than they were in the early 1800s. Nevertheless, there remained many sceptics who instead preferred the suggestion made by Charles Lyell in 1833 that erratics, drift deposits, etc. were deposited as icebergs melted. The formal proposal of the glacial theory came in 1837, when the Swiss zoologist Louis Agassiz presented the theory to the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences. Eventually, Lyell and other eminent natural scientists such as William Buckland, Professor of Geology at Oxford University, accepted the glacial theory. By 1860 it had achieved widespread approval and had set in train investigations that developed the theory further. For example, by 1863, Archibald Geikie, a Scottish geologist, had suggested that several glacial stages had occurred, and thus originated the idea of multiglaciation with cold periods, or ice advances, being separated by warm stages or interglacials. Archibald Geikie’s brother, James Geikie, proposed in 1877 that four distinct glaciations had occurred in East Anglia, whilst evidence for multiple glaciation was found elsewhere, such as the American midWest and Europe. Of particular importance was the proposal in 1909 by Penck and Brückner, two German geographers, that the river terrace sequences of the Alpine region could be ascribed to four distinct series with each terrace having been formed during one of four successive ice ages. Their scheme is illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 The succession of European ice ages as determined by Penck and Brückner in 1909

Source: Based on Imbrie and Imbrie (1979)

1.2.2 Related developments

Much research was taking place in areas beyond the limits of glaciation. For example, in 1882 Ferdinand von Richthofen, a German geologist, proposed that deposits of a fine-grained yellow sediment over vast areas of Europe, Asia and North America were loess deposits; these originated as silt from glacial meltwaters at glacial margins and were then blown into continental interiors. The American geologist Grove Gilbert presented evidence in 1890 to show that the Great Salt Lake of Utah was a remnant of a much larger lake. This and related work gave rise to the suggestion that periods of high rainfall, i.e. pluvials, alternated with dry episodes, i.e. interpluvials, which may have been synchronous with glacial and interglacial stages respectively. Subsequently, work in lowlatitude regions attempted to relate results, often erroneously, to pluvial and interpluvial stages.

It was also recognised, and formalised by the Polish geomorphologist, von Lozinski, in 1909, that as ice sheets expanded, the bordering tundra zone would also extend into areas occupied by boreal and/or temperate forest and give rise to Earth surface processes characteristic of regions close to ice sheets, i.e. periglacial ...