- 350 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Innovating at the Edge

About this book

All organizations who are looking to improve performance through embracing new ideas, work in new ways, create new products and services, challenge the status quo or redefine their existing business environment have much to gain from this book. 'Innovating at the Edge' not only provides readers with an informed understanding of the latest developments in innovation practice but also presents them with the bigger picture. This enables them to determine how to build these advances into overall development of their own innovation capabilities and how to capitalize on the benefits available to them.

Today as the new economy is brought into line with the old, increasing fragmentation of a global economy drives change across multiple sectors. Organizations operating at the leading edge of the innovation paradigm are adopting a whole new set of approaches to help them redefine the present and build the future.

Learn how companies such as Egg, Dyson and Smint are redefining their markets, how organizations such as ARM and Qualcomm are deriving their soaring revenues wholly from licensing, and how firms such as Nokia and Nike are constantly evolving their product portfolios and associated value propositions. These real-life examples provide key lessons for all involved in creating and delivering new businesses, products and services.

Readers will understand where all these strands fit within an overall context of innovation evolution, and recognise that the inter-relationships between strategy, process and organization are the key enablers for achieving innovation improvements. Firms can then grasp and appreciate what they need to do in order to emulate these innovation leaders operating at the edge of contemporary practice.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Part 1

Evolution of innovation capability

Introduction to Part 1

The last two decades have seen an increasingly faster development of the art and science of innovation than at any other period in history – faster even than the peak years of the Industrial Revolution. Companies across the world have embraced new technologies, created new processes, exploited new markets, formed new organizations and realized new strategies – all to enable improved development and delivery of new products, services and businesses. This has occurred not just in one specific lead sector but throughout industry, from computing and consumer products through to pharmaceuticals and retail.

As firms have sought to enhance their approaches to innovation in order to improve performance, they have evolved practice and, in doing so, created, built and integrated new innovation capabilities within the organization. Many have experimented with new ideas for stimulating, organizing, prioritizing, managing and enabling innovation to deliver increased benefits to the firm, its customers and its suppliers. Some of these ideas have failed or, although ideal in theory, have proven to be unsustainable in practice. Others, however, have worked well and achieved – and sometimes exceeded – the desired objectives. These have consistently delivered the improvements they were envisaged to, and as such have become a core part of the day-to-day practice within the originating organizations. Moreover, on the back of this, many of these improvements have subsequently been successfully migrated across sectors. They have proven themselves to deliver benefits in organizations large and small, and to enhance performance equally from one industry to another. For many firms these have, in effect, been translated into the mainstream of innovation practice and gradually become the standard de facto approach.

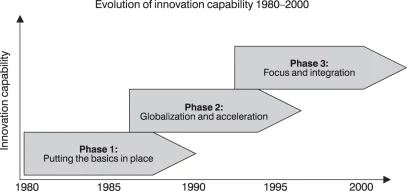

Reviewing the past twenty years, there have been three main waves of new approaches that have occurred across industry. These distinct waves have each had a different focus, followed different schedules and been comprised of differing techniques and approaches, and have all had a significant impact on corporate performance across the board. At the point of first development and introduction, these waves have all come to represent the leading edge of innovation practice for the time and, as each component approach has gradually been adopted across industry and become standard practice, have in turn stimulated the next wave of new ideas, and thereby the new edge, to take shape. As organizations have integrated the previous wave into the core of their operations to build their innovation capabilities, so new approaches that can be used on top of, in parallel with or sometimes even instead of existing methods have evolved innovation best practice. These three waves have, at heart, addressed several core common issues:

• 1980–1986: Putting the basics in place

• 1987–1993: Globalization and acceleration

• 1994–1999: Focus and integration.

The three waves of innovation capability evolution have had an impact on all aspects of a firm’s operations, from strategy and process to organization. As you delve into the individual elements that comprise these waves of leading edge practice and examine where and when they were first introduced on a recognizable scale, the elements can be generically grouped into seven main areas:

1 Strategic impetus – the corporate theme that has driven innovation

2 Market focus – how innovations have been presented to customers

3 Product attribute – the differentiating feature for new products and services

4 Activity effectiveness – the key component for successful innovation delivery

5 Development process – how new products and services have been delivered

6 Enabling organization – the structure of the group delivering innovation

7 External alliances – how firms work with partners to realize innovation.

It is across all seven of these areas that individual improvements in innovation practice have occurred and continue to occur. As the edge of innovation practice has moved on, each time new approaches in these seven areas have emerged and been introduced.

Today, we are into a fourth wave of innovation capability development. Although many firms are still grappling with some of the issues presented in earlier phases of this capability evolution, there is, across different sectors, a whole new portfolio of approaches being tried out, proven to deliver improvement and thus being adopted by other firms seeking to emulate this. These are the new approaches to improving performance that will tomorrow become standard. We are now in the middle of this fourth wave of innovation capability evolution, and today this is the leading edge. Companies that are developing and refining the new techniques for innovation success are today at the forefront of innovation practice. They are ‘innovating at the edge’.

This first section of the book focuses on the varied approaches that have, over the years, formed the first three waves of the leading edge of innovation. Through examining each of the seven component approaches that have been used and subsequently migrated into the mainstream, and highlighting leading adopters in each wave, it provides an overview of where we have come from and where some companies are now. In doing so, it not only gives a contextual framework for the development of an organization’s innovation capability, but also identifies they key challenges for firms adopting these approaches both today and in the future.

3

Phase 1: Putting the basics in place

The first major period of recent advance in how organizations have taken their ideas to market occurred in the early to mid-1980s, when companies facing the challenges of increased competition and more rapid technological advancement sought to accommodate several new challenges. This was when firms as diverse as Sony, IBM and Dow all started to formulate product strategies as a distinctive element and dependency of their overall corporate strategy. How innovation could be used to create, develop and support an evolving portfolio of new products and services focused on future revenue and margin growth was being considered in a proactive manner for the first time. Product strategy emerged from under the wings of either overall business or marketing and sales strategies, and came into the limelight.

At the forefront of this was the increasing role of technology in creating and enabling the development and introduction of new products and services. From semiconductors to composite materials, database management software to the first call centres, the adoption of new technology became a core strategic focus for many companies, and as a means of effecting this the management of external alliances to facilitate the transfer of the appropriate technologies from lead innovators, universities and other research establishments became a key challenge. Understanding the technology, never mind selecting the most appropriate type for an application, was a major headache for many. Furthermore, ensuring that access, integration, upgrading and support were managed in a coherent and focused manner was, in many cases, frequently being seen less as a black art and more as a core corporate capability.

At the same time, although largely focused on their regional markets, companies were increasingly aware of issues such as quality and reliability. The advances being made by Toyota and other companies in the automotive industry were having widespread impact as more organizations adopted the total quality mantra in their bid to improve idea delivery and support. In addition, as growth generated from new products and services became ever more important, many organizations began to establish dedicated resources focused on idea creation, selection and delivery. To support this, they also began to introduce recently created improvements such as stage-gated development processes. Together this combination of focused resources and defined processes helped to deliver the first significant improvements in the efficiency of innovation activities across the board. This was thereby the first wave of improved innovation capability, where many organizations started to put the basic elements of a coherent approach to innovation in place.

3.1 Product strategy

During the post-war period, when attention was first being paid to product innovation activities and the supporting processes, there was constant growth in the number, range and type of new products being produced. As more disposable income became available for purchases and the real cost of production fell due to increased production efficiency, existing markets continued to grow and new markets, many outside the industrialized world, began to evolve rapidly. Simultaneously, new needs were becoming apparent and advances in new technologies were enabling fundamentally new consumer products such as colour TVs, transistor radios, dishwashers and instant cameras to be realized and launched. The corresponding, largely organic, growth of markets and opportunities led many manufacturers to produce more and more variants of products and broaden their product ranges, often diversifying into new areas to satisfy burgeoning needs.

However, while this resulted in a basically uncontrolled evolutionary development of company activities, technologies and resources as many manufacturers’ new products were either led by the demands of the developing markets or pushed by newly invented technologies, this period was also the time when some companies began to think more strategically about what products to make and how to determine new product ranges (McGrath, 1995). During the early 1980s, manufacturers and service organizations started developing new product strategies (Cooper, 1984). As leading companies Philips, IBM and American Express, to name but a few, were identified as using clearly planned product strategies and their respective methodologies explained, more and more paid attention to the area (Mintzberg, 1994). The significance of the different benefits to be gained from adopting alternative approaches, such as providing high volumes of product or service each with a low profit margin as opposed to low volumes of high-profit-margin products, was becoming more apparent. As many of the funding financial institutions also became interested in what new products firms were developing, details of which specific products would provide the best returns were first explored (Devinney and Stewart, 1988). Companies seeking to address the needs of developing markets began to reassess their new product lines, identify which were most appropriate to the market and their organization and focus attention on their development (Cooper and Kleinschmidt, 1987). As companies have since sought to access new markets and increase their revenues, the strategic perspective of which products to develop, where to produce them and how to deliver them has now developed into a sophisticated activity in its own right. As a key part of this, product design in terms of the visual and ergonomic dynamics was also first viewed as a key success factor. Product strategy became seen as a core activity within corporations – not just in large multinationals but also in many smaller companies, particularly those in areas dependent on high technology, where investment in innovation and product development is often high (Pavia, 1990). It was also during the early 1980s that companies first began to categorize the different approaches to product strategy that were available, the three key alternatives seen at the time being offensive, defensive and imitative strategies (Freeman, 1982).

• Offensive product strategies were characterized by significant R&D activity developing new technologies and processes to enable companies to be first to market with new products and services. As market and technology leaders, firms adopting this strategy were seen as being dependent on access to the latest information about emerging technologies, market trends, consumer behaviours and economic indicators. Although frequently considered to be high risk because of the uncertainty and the high levels of investment often required, this approach was also seen to be one where the returns were significant. Key exemplars at the time were Pilkington with its float glass products, chemical company DuPont and its Teflon coatings, and, in the financial services sector, Diners Club as the lead charge card product.

• Defensive product strategies were by contrast seen as being less dependent on creating the new market or technology, but more on developing it further. Using an organization’s skills and capabilities in production, delivery, and sales and marketing, the main objective was to introduce competitively priced follow-on products and services in large volumes to gain a significant share of a growing market. Although evidently less risky than offensive product strategies, as it focuses on improving existing products, this approach relies on a very good understanding of markets and buyer preferences, coupled with an ability to identify and satisfy short-term expectations. Matsushita was the leader in this arena, being the most successful close follower of JVC in the VHS/Betamax war with Sony – largely achieved through efficiently introducing a continuous stream of market tracking incremental improvements to the core VCR products. Similarly, Microsoft’s Word software was a successful follower of the preceding WordStar product, just as Nissan produced highly reliable but low-cost alternatives to Ford and GM vehicles.

• Imitative product strategies were in some ways similar to the defensive approach, as they focused on the provision of follow-on products and services, but rather than developing incrementally improved versions they relied more on taking advantage of localized markets and the ability to manufacture low-cost clones. Either through licensing patents or core technology acquisition, but without any significant R&D expenditure, many firms, often in developing countries, chose this approach to copy the market leaders, benefit from their earlier innovation and grow in domestic markets before competing on the world stage. Compaq’s first PCs were IBM clones, using identical technology but at lower price; drinks companies Budweiser and Molson copied the ‘dry’ brewing process from the Japanese Asahi and Sapporo leaders; and in Korea Daewoo cloned GM and IBM products and Samsung started off by making low-cost versions of Sanyo TVs and Sharp microwaves. Compaq and Samsung particularly used low-cost, high-volume imitative strategies as the precursors to move on up the value-chain into the more profitable defensive and offensive approaches.

In parallel to these three strategies, outside the high technology areas several firms continued to pursue a niche traditional approach to product strategy. In established markets where there was little call for innovation at the time, firms such as Barbour, Aga, Le Creuset, Mont Blanc, Coutts, and Fortnum and Masons all continued to provide the same products year on year. By a dictate of fashion and clientele, a number of such areas where brand-linked established goods were able to create and satisfy demand, this approach continued to provide revenue, if not generate significant long-term profitability. This choice of product strategy was largely a result of consequence rather than intent. Organizations seeking to grow would rarely consider this as an entry strategy to the ever-increasingly competitive world of new product and service provision.

From around 1980, product strategy was thus first seen as a distinct but component element of overall corporate strategic intent. Raised from subordinate afterthought to an equal standing with marketing and production on the boardroom agenda, the determination of which products and services to provide, in which markets, using what delivery mechanisms and embracing what technologies to address which issues, were all, for the first time, being considered in a collective coherent manner. Although at the time emergent globally in organizations as varied as Braun, Unilever and IBM, one of the best examples of how a company moved from a pure technology-driven approach for development to a coherent offensive product strategy where technology adoption is coupled with leading edge design and clear market segmentation is Sony, the Japanese consumer electronics company.

Sony: technology meets design

S...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Author profile

- Introduction

- Part 1: Evolution of innovation capability

- Part 2: Innovating at the edge

- Part 3: Focus and integration

- Conclusion and resources

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Innovating at the Edge by Tim Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.